Orders in hand, Glass steamed on for Guam and whatever resistance the Spanish offered.

In 1898, the United States went to war against the ailing remains of the Spanish Empire. Public outrage at the brutal revolution occurring in Cuba, coupled with the destruction of the American battleship U.S.S. Maine in the port of Havana, Cuba, reached such a pitch that only war would quell the outrage.

Unprepared and underequipped, the United States went to war for the time-honored traditions of freedom and protecting its economic interests.

While the Army focused on liberating Cuba, several members of the US government worked to orchestrate the capture of Spanish possessions and territories in the Pacific. While the Philippines received the most attention, smaller islands like Guam were not ignored, at least not by the Americans.

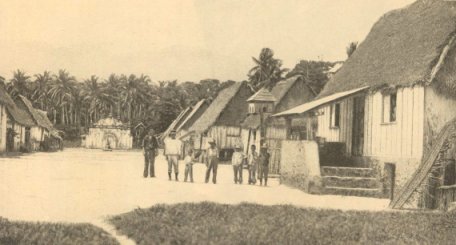

The small Spanish garrison at Guam lay all but forgotten by its imperial masters. The United States, however, did not forget the remote island.

The territory’s proximity to the Philippines made it an excellent staging ground for operations there and across the Pacific. If America was to become an empire in the Pacific, it would need such ports to extend its logistical arm.

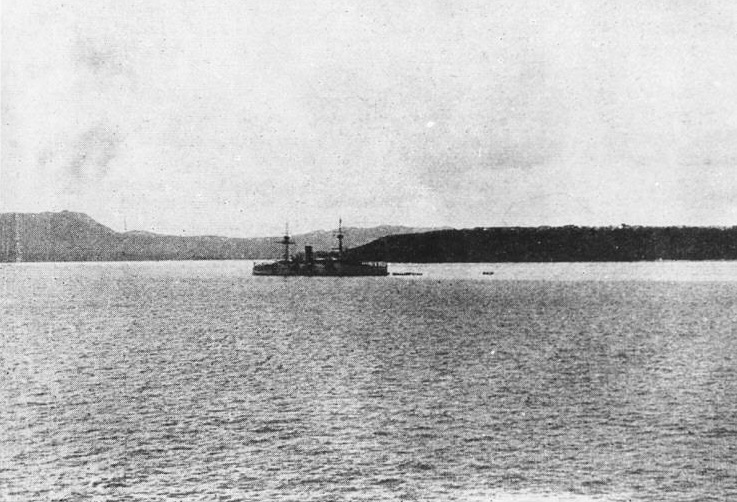

The capture of Guam would fall to the naval cruiser U.S.S. Charleston, under the command of Henry Glass, whose career dated back to the Civil War, like many of the senior commanders of the upcoming war.

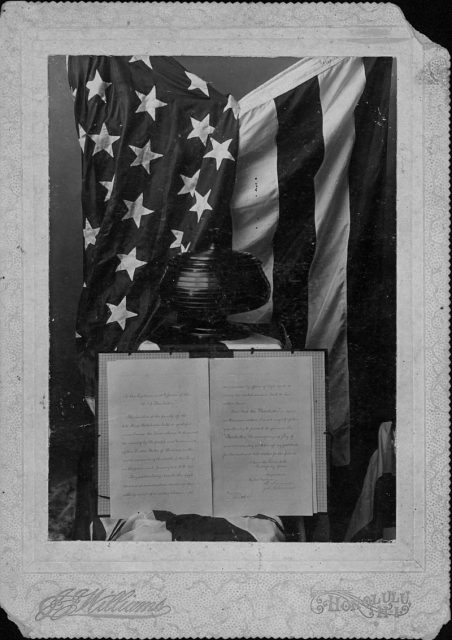

While in port at Honolulu, the Charleston met three transport ships, one containing a message for Glass. The message contained orders stating that “Upon the receipt of this order, which is forwarded by the steamship City of Pekin to you at Honolulu, you will proceed, with the Charleston and the City of Pekin in company, to Manila, Philippine Islands.

On your way, you are hereby directed to stop at the Spanish Island of Guam. You will use such force as may be necessary to capture the port of Guam, making prisoners of the governor and other officials and any armed force that may be there.”

Charged with also destroying any Spanish fortifications and naval vessels, Glass’s orders contained instructions for nothing less than the full conquest of Guam for the United States. His orders stated the operation should take only a day or two.

Orders in hand, Glass steamed on for Guam and whatever resistance the Spanish offered.

Arriving on June 20, Glass and his officers observed a lonely port bereft of Spanish vessels. The presence of the Americans got the attention of the locals. With no naval targets in sight, Charleston proceeded to fire 13 shots at the fort, all of which missed.

However, the Spanish failed to return fire, and this confused the Americans as they waited for a response.

The Spanish, having joined the natives and prominent local merchants in observation, prepared to respond to the American gunfire — but not with a volley of their own. Instead, the Spanish military commanders, along with a naval surgeon to act as interpreter, piled into a rowboat and went to greet the American visitors.

The commanders had last had contact with the Spanish government two months earlier, so they knew nothing of the war. They thought the American gunfire was a salute, so they went to meet with the Americans to apologize that they could not return the salute because they were out of powder.

Glass wasted no time informing the Spanish that the two nations were at war and that they were now prisoners of war. The astonished Spanish were paroled to inform the island of their bloodless capture.

Seeing the writing on the wall, a prominent merchant named Francisco Portusach sailed under an American flag to meet with the Charleston. When the Americans questioned why he was flying an American flag, the merchant grinned and produced his naturalization papers.

Read another story from us: Spanish Galleons: The Stallions of The Sea

Francisco Portusach, known as Frank by the Americans, quickly found himself governor of the newly conquered American territory. With just 13 poorly aimed shots, Glass managed to capture a Spanish port and post its new governor.

The Spanish garrison, lacking knowledge of the war, ships, or even gunpowder to combat the Americans, bowed to the inevitable. Guam fell to a loan cruiser and a handful of transport ships in quite possibly the easiest battle in American history.