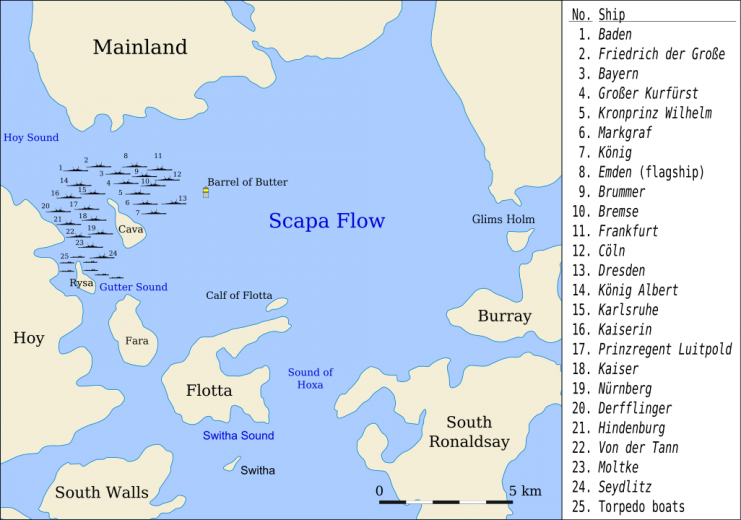

The Orkney islands sit above the north east coast of Scotland and this is where the Royal Navy made a shelter in the anchorage of Scapa Flow. It was seen as a safe haven and this remained the case until the conflict that occurred twenty years after the events discussed here.

The only trip I have made to Orkney was back in a now hazy early 1990s. I stayed in what I can only describe as a combination of white asbestos, chipboard, assorted bits of wood and corrugated iron where I shivered under a damp candlewick bedspread looking out on days of monsoon. It was June.

The ‘holiday home’ my then wife and I had rented stood on the banks of Scapa Flow surrounded by clumps of narcissi that clung on determinedly as the wind and rain swept in.

She hated the place with a passion and my enthusiasm was waning when we finally decided to cut and run back to the mainland in search of summer.

But I fondly remember one brief glorious afternoon when the sun won through to shed colour all over the stunning vista beyond the flower beds. Scapa was revealed and it was awesome. The flicker of lights from the distant refinery at Flotta and the appearance of a tugboat added to the magic.

Somewhere out there were the remains of the German High Seas Fleet scuttled in 1919. I was enthralled by the event and devoured a copy of the late Dan van der Vat’s gem The Grand Scuttle I bought in a shop in Stromness and I still have it.

It remains an ideal account of the momentous events that took place in that historic year. The Armistice that brought fighting in World War One to an end was seven months old, but the real business to draw a line under the conflict were taking place in Paris.

Peace talks rumbled on, but although much had been addressed there was every sign the German government would refuse to sign the final treaty.

The sailors of the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet had led the mutiny that helped bring the Hohenzollerns crashing down and the fleet had not sailed for one last clash with the Royal Navy.

Instead, the ships endured the ignominy of being held hostage at Scapa Flow where the commander, Admiral von Reuter, awaited news from Paris. He became increasingly unsettled as time dragged on, fearing the resumption of hostilities threatened by the Allies if the Germans failed to agree to the terms the men in Paris demanded.

He relied on news from days old newspapers and the inability to follow the talks in Paris in real time led him to make a fateful decision.

Although discipline was poor on many of his ships, the admiral knew that there was a big enough sense of pride within the fleet to ensure his determination that the German ships should not be taken by force. The fleet would scuttle itself if a return to war seemed imminent.

Admiral von Reuter misinterpreted the available news from Paris and gave his orders to for the scuttle to begin on 21st June 1919.

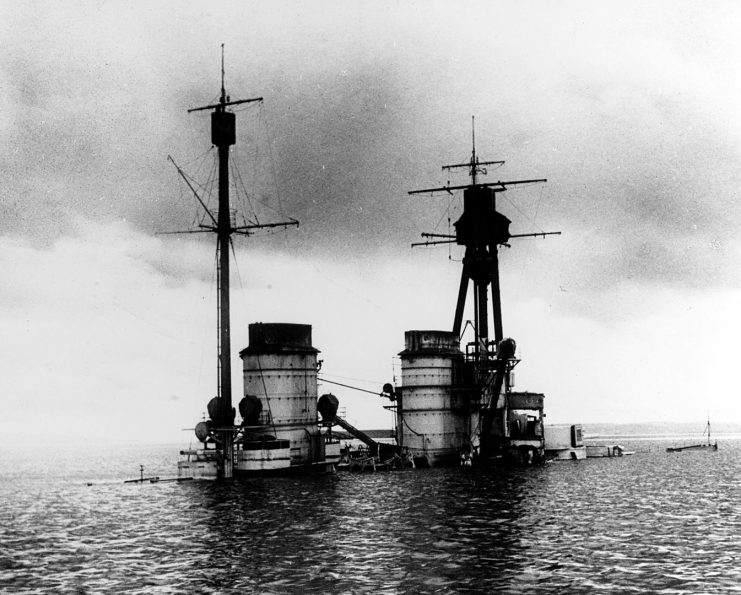

There followed an incredible drama as German sailors attempted to wreck seventy-four ships in the anchorage at Scapa Flow. Events unfolded relatively slowly as, with their seacocks opened, ships of all sizes began to founder.

The grand scuttle was not noticed, at first, by the sailors manning guard ships and boats of the Royal Navy; but this would change.

One of the greatest incidences of self-destruction in modern times was under way. A party of schoolkids on a sightseeing boat trip were some of the witnesses of the scenes that followed. In the end twenty-two of the seventy-four were prevented from sinking, but the remainder were wrecked.

Innes McCartney describes the day with great style. His account cracks on because as dramatic as that mad day was, his book spends much more time looking at events that followed.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like to witness a host of great battleships and battlecruisers turning turtle, or the sight of lines of destroyers and torpedo boats coming to grief; but for me the deeper fascination is in the huge salvage operation that took place over the following decades.

Dr McCartney covers the salvage effort in great detail. I have seen and worked with many press photos of the operation and had the pleasure of scanning original negatives. Each time I do this I am amazed at the scale of the enterprise, and this is coupled with a strong interest in the people who did it.

Chief among them was Ernest Cox, a clever and determined man who saw a way to make a lot of money from the salvage. Things didn’t work out quite as he intended, and the job cost him a fortune.

Although Cox and his partners did not finish the job, the ships were gradually released from their watery graves to be floated away for destruction. I’m sure I read in The Grand Scuttle that some of the recovered steel found its way into making the Apollo space capsules.

The author is a nautical archaeologist who knows all about exploring shipwrecks. This wonderful book allows him to share with us the remnants of the German fleet. We see the sites where the ships were scuttled and the debris fields of the salvage operation.

For me, the deeper fascination remains in all of this. Dramatic as it was, the grand scuttle was just the first day of decades of activity; the looting and random bits of salvage followed by more serious local efforts and the industrial enterprise of Ernest Cox and his ilk to raise the ships for profit.

But not all the vessels were taken away and there is something quite haunting about the eight ships of the Kaiser’s fleet that remain at Scapa Flow. They are a magnet for divers and represent an important facet of the modern life of Orkney. I wonder if Ludwig von Reuter and his officers could ever have imagined that this would be so? The wily old admiral died in 1943.

Innes McCartney has produced a book to more than match his superb exploration of the wrecks of ships lost at the Battle of Jutland published a few years back. He has the knack of bringing events and long-lost ships to life and I cannot get enough of this sort of stuff.

This magnificent book is as forensic as it is spiritual, and I am sure this is down to the enigma of sunken ships as much as anything else. The mysteries of the deep such as these never cease to amaze. I really hope we get to see more of the same from this author in the years to come.

Another Article From Us: Historic 104-Year-old Battleship Close to Sinking

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

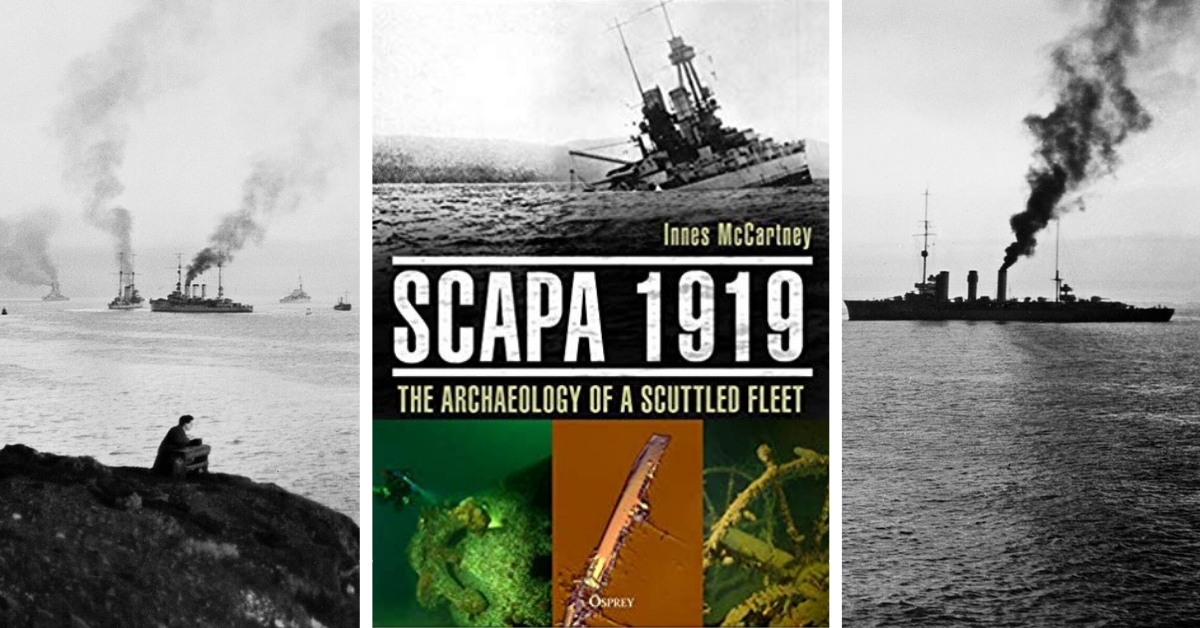

SCAPA 1919

The Archaeology of a Scuttled Fleet

By Innes McCartney

Osprey Publishing

ISBN: 978 147282 890 3