The Scirè was a small Italian coastal submarine that entered service in April 1938. Its name commemorates an Italian victory in Ethiopia in March 1936. Its crew had 36 men, including four officers.

197 feet long and 21 feet wide, Scirè was powered by two 1,400 Cv Fiat engines and two 400 hp Magneti Marelli electric motors, which gave it a maximum speed of 14 knots on the surface. It had a variable range of 3,180 nautical miles with a cruising speed of 10 to 14 knots. When submerged, its maximum range was 74 nautical miles at the speed of 4 knots.

Scirè‘s armament consisted of a 100/47 Mod 35 cannon which could fire 152 rounds per minute, two 13.2 mm Breda Mod 31 machine guns (1.500×2 r/m), and six 533 mm torpedo launchers, four at the bow and two at the stern.

Early World War II

Under the command of Lieutenant Adino Pini, in July 1940 Scirè participated in actions during which the French steamer Cheik was sunk off the island of Asinara, near north Sardinia. Scirè then rescued the survivors.

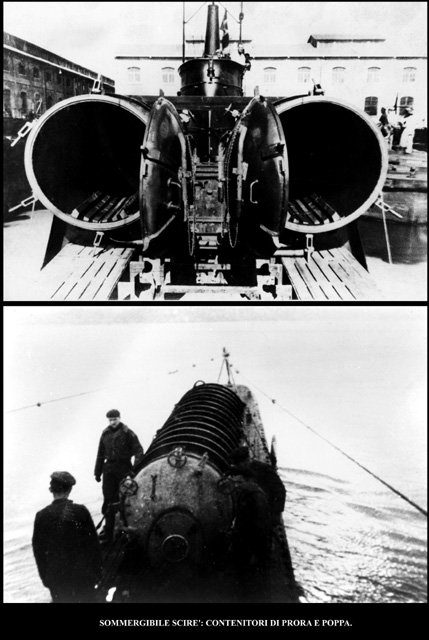

In August 1940, Scirè became part of the X Flottiglia Mas, also called La Decima (“The Tenth”) and was modified as a result. The 100/47 cannon was removed, and the tower was modified in order to reduce its weight and accommodate three watertight tanks on deck.

These tanks were resistant to pressure at a depth of 295 feet (90 meters). One was located at the bow and two at the stern, and each one contained a manned torpedo (Siluro a Lenta Corsa, or SLC). These were basically tiny–and slow, hence their name–submerged vessels, operated by a pair of divers, that could be used to stealthily bring a torpedo up close to a target.

Another expedient to enable Sciré to bring the offense to the enemy was painting the sub light green so it would blend in with moonlight. Also, the outline of the bow of a fishing vessel was painted on the stern. After these modifications, Sciré was ready for more action.

Port of Gibraltar Missions

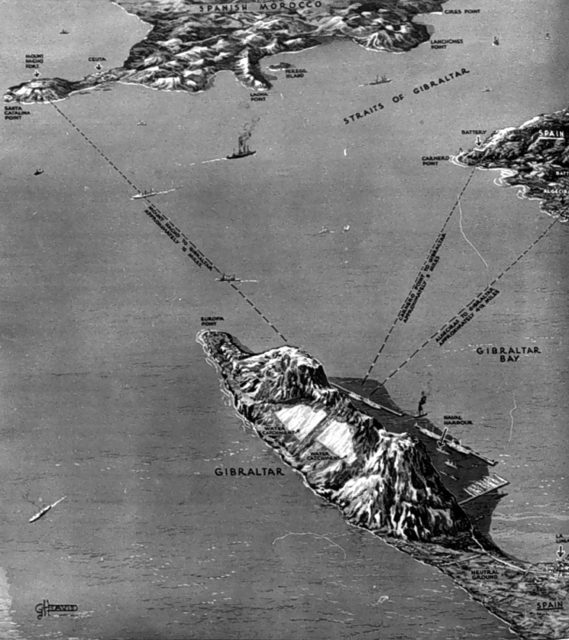

BG1 operation was scheduled for September 24, 1940 with the objective being the Port of Gibraltar. However, Sciré was about 50 miles from the destination when the order to cancel the mission came in.

The enemy ships that normally were in that port had sailed out to protect two convoys. Scirè stopped at La Maddalena in Sardinia before returning to its base at La Spezia, in Liguria.

BG2 operation took place on October 21 at the Port of Gibraltar. On board Sciré were six operators for the three SLCs. The mission was a failure because all three torpedoes had technical problems.

One of the torpedoes was abandoned by its operators, and proceeded along the Iberian coast with the engine still functioning. The British had the opportunity to examine it from afar before it was taken to a Spanish arsenal.

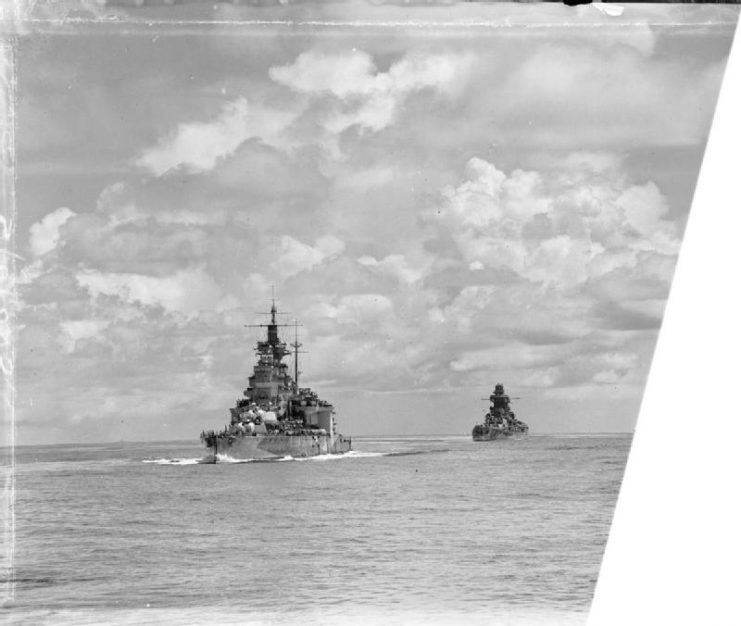

Only the SLC piloted by Lieutenant Birindelli came within 230 feet of the battleship HMS Barham. Birindelli decided to blow up the charge when he could bring the torpedo no closer. He was taken prisoner, and would return to Italy three years later.

Sciré and the rest of its crew and divers returned safely to Italy after this unsuccessful event. The mission did offer the opportunity to fine-tune the functioning of the SLCs and the divers’ respirators.

It also enforced the conviction that the submarine was able to elude the enemy’s harbor defenses, and that the divers’ physical capabilities were sufficient for their missions to be successful. However, it was decided that in subsequent operations the divers would be brought by plane to a location as close as possible to their objective before boarding the submarine.

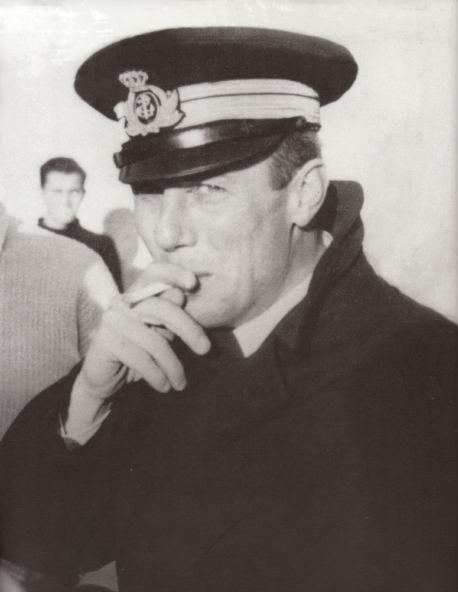

BG4 operation. After another aborted mission, on September 10, 1941 Scirè set out for Cadiz, arriving after an eight day transit. There the transfer of specialists to pilot three SLCs took place. At 11: 30 PM on the 19th, Commander Borghese received information on the positions of the ships in Gibraltar Harbour.

An hour later, Scirè settled at the mouth of the Guadarranque river and launched the SLCs. This time the mission was successful because the operators were able to place explosive charges under the keels of several tankers.

MS Durham remained inoperative for a long time after being damaged. Fiona Shell broke in two and sank. RFA Denbydale remained afloat, but had a broken keel and was stuck in the port. It was used as a barracks and fuel depot until its demolition.

The submarine went back to its base, La Spezia, and was tasked with a new mission.

Mission at Alexandria

On December 3, 1941, Scirè left port and on the 12th it embarked the crews of the three SLCs: Durand de La Penne and Bianchi for SLC 221, Antonio Marceglia and Spartaco Schergat for SLC 230, and Vincenzo Martellotta with Mario Marino for SLC 223.

Two days later Sciré departed for Alexandria, waiting for news on its targets. Italian Royal Air Force reconnaissance finally provided the expected news.

The submarine reached the proximity of its objective around 2:15 AM on December 18. It submerged and proceeded to an area a little more than a mile from the western pier of the commercial Alexandria port lighthouse. The release of the SLCs occured late in the evening.

The results of this action ensured Scirè’s fame. SLC 221 severely damaged the British battleship HMS Valiant, and four months were lost in repairing it. SLC 220 put the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet flagship, out of commission for a year and a half. SLC 223 damaged the tanker Sagona and the destoyer HMS Jervis, which was moored alongside it for refueling.

The SLCs operators were all captured and transferred to prison camps, to be released only after Italy surrendered. Upon their return to Taranto after the surrender, the six men received the Gold Medal for Military Valour. It was pinned on their breasts by Commodore Sir Charles Morgan, former commander of HMS Valiant.

Scirè had traveled 3,500 miles to accomplish the Alexandria mission. Its commander and the ship’s combat flag were awarded with the Gold Medal. The submarine remained in port until July 1942, when an attack on the enemy at the port of Haifa took place.

Mission at Haifa

On July 27, 1942, Scirè left La Spezia. On August 2 it arrived in Lero to pick up two officers and nine non-commissioned officers and sailors, including its SLC divers.

Action was scheduled for August 10. Unfortunately, after that date there was no news of the submarine and its men. Searches were unsuccessful. On August 31, 1942 the unit was declared lost in action at sea.

Only some time later it became known that the German Enigma encryption code had been deciphered. The British, informed by their Intelligence, therefore knew about Scirè‘s mission.

After locating it, the British allowed the submarine to arrive undisturbed at the entrance of the port. An intense depth charge bombardment forced it to emerge, and a naval trawler called Islay sank Scirè in the Bay of Haifa with the participation of the Royal Air Force and coastal artillery.

In 1984, the Italian rescue ship Anteo recovered 42 bodies of the 49 crew members and operators who had been lost. Parts of the hull were also recovered and are now displayed in the naval museum at Augusta, at the Arsenal of La Spezia, and in Venice. The periscope is at the Vittoriano in Rome.

Sciré’s Gold Medal citation (approximate translation)

[Sciré] operating in the Mediterranean, already recovering from lucky ambush missions [and] designated to work with the assault department of the Navy in the heart of enemy waters, participated in repeated [attacks on] extensive Mediterranean bases.

During the repeated attempts to reach [its objective], it encountered the most bitter difficulties created by the violent enemy reaction and by the conditions of the sea and currents. After having overcome, with the most absolute contempt of danger, the obstacles posed by man and nature, it was able to perform completely the task entrusted to it, emerging a short distance from the entrance of the heavily armed enemy bases to launch the special weapons which caused the sinking of three large steamers in Gibraltar. In Alexandria serious damage [was caused] to the two battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant, whose total sinking was avoided only because of the shallow waters in which the two ships were moored.

Later, during another particularly daring mission, it was ruthlessly attacked and disappeared in the enemy waters, thus closing its glorious warlike past.

Read another story from us: The Italian “Acqui” Mountain Infantry Division Disaster, Kefalonia, 1943

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

All frogmen/divers members of the above missions were awarded Military Value’s Gold Medal.

A diver has written in his report:

In addition to ours (Italian), a plaque of the Israeli navy and an unknown hand left, broken but on which you read clearly the English words “heroes” and “meditate” definitively stipulate that the glory of the Scirè and the courage of his men are not Only Italian heritage.

Authors:

Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi

Melvin Jones Fellow