Indeed, General Sheridan was wounded during the Civil War, but did not die in battle

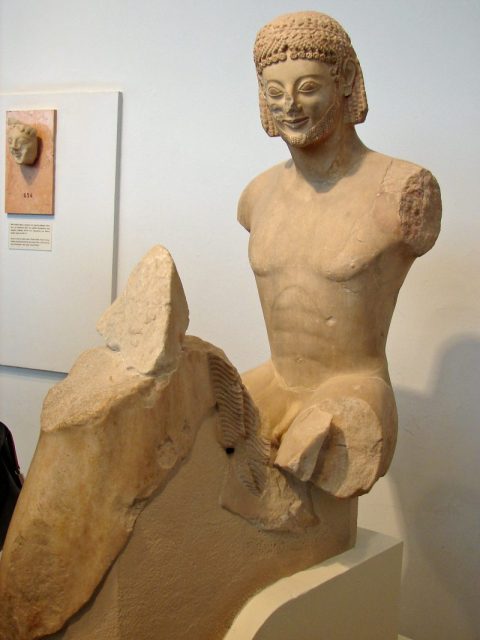

The depiction of wartime heroes, royalty, and similar important figures in the form of equestrian statues dates back to the sixth century BC. The Rampin Rider statue from ancient Greece is the oldest known piece of equestrian statuary in the West.

The symbolism of equestrian statues is a rather interesting subject, with some people opining that the depiction of the horse’s feet gives a hint about the rider’s fate.

Particularly in the United States, the urban legend goes thus:

- If the horse has one hoof in the air, then the rider was wounded in battle—and may have died later from the wounds.

- If the horse has both hooves in the air, then the rider was killed in battle.

- If the horse has all hooves on the ground, then the rider survived all battles uninjured and later died of natural causes.

This intriguing deduction has over the years been popularized by many a tourist guidebook, the most popular of which is the 1987 book Hands on Chicago written by Mark Frazel and Kenan Heise. A paragraph of this book says:

“At Sheridan Road and Belmont Avenue, the statue of [General] Sheridan beckons troops to battle. The horse General Sheridan rides is named Winchester…Winchester’s raised leg symbolizes his rider was wounded in battle (the legs of [General] Grant’s horse are on the ground, meaning he was not wounded).”

So is this idea, in all its glamour, just a myth? Or is it fact?

It should first be noted that the idea of a tradition of signaling the fates of riders in the hooves of their horses has been debunked by the U.S. Army Center for Military History. If the words alone of the historians of the U.S. Army are not enough, perhaps a walk through Washington D.C. would suffice to confirm what they say.

Washington D.C. is the city with the largest collection of equestrian statues in the world. Among this vast collection of horses and riders, only about 7 out of 29 that were analyzed have been found to conform to the myth.

Moreover, there are cases in which multiple statues of the same person are contradictory. Take General Philip H. Sheridan for example: an equestrian statue of General Sheridan in Washington D.C. depicts the horse to be standing on all four hooves. Two other statues in Chicago and New York show the horse to be raising one hoof.

Indeed, General Sheridan was wounded during the Civil War, but did not die in battle. So if the tradition holds true, the horse should have one hoof in the air, like the statues in New York and Chicago. But the one in Washington D.C. goes against the tradition.

Another notable statue in Washington D.C. is that of General Andrew Jackson, in Lafayette Park. This equestrian statue is the oldest statue in Washington D.C. The horse in this fine piece has both forelegs in the air. However, Jackson died of tuberculosis and heart failure, not in battle.

There have also been cases in which one sculptor made several equestrian statues without following the tradition. One such case involves the famous Irish sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Sometimes his statues follow the tradition, sometimes they don’t.

This suggests that the posture of the horses in each statue would merely be dependent on the choices and skills of the sculptors, and conformity with any supposed tradition could be dismissed as simple coincidence.

Perhaps a confirmation of the myth can be found in the equestrian statues erected in memory of the Battle of Gettysburg that took place during the American Civil War. If we consider only the statues that commemorate Gettysburg, the majority of them do conform to the tradition.

However, with even just one statue going against the tradition, claims of secret messages should be taken with a pinch of salt. And there is one Gettysburg statue that fails to adhere to the tradition: that of Lieutenant General James Longstreet. The highly controversial but talented Longstreet was not wounded at Gettysburg. However, the horse in his equestrian statue has one hoof in the air.

The same principle can also be said of equestrian statues in Europe in general: If such a tradition exists, there should be some widespread consistency to it. Some non-American examples of statues that ignore the tradition include those of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Emperor Constantine, and King Louis XIV.

Aurelius’ statue has one hoof in the air, but there is no record of him ever being wounded in battle.

Constantine’s statue has his horse rampant—with both legs in the air. However, it is a well-known fact that he did not die in battle.

Read another story from us: Andrew Jackson – Politician General in War of 1812

King Louis XIV also has a statue with his horse rampant. Contrary to what the equestrian statue tradition would say, King Louis XIV died of gangrene, and not in battle.

With all this, it is safe to say that the tradition does not hold up to scrutiny.

Admittedly, it would have been quite fascinating if such a tradition were proven to be true. However, because there is no strong proof of its credibility, it remains what it has always been: a myth.