He fought in WWI and became an American hero with nine medals. After the war, he met three presidents and attended university despite standing a mere 22-inches tall with four legs and a tail.

In July 1917 at New Haven, Connecticut the 102nd Infantry Regiment of the 26th Yankee Division were training at Yale University’s football stadium when an unlikely hero wandered in.

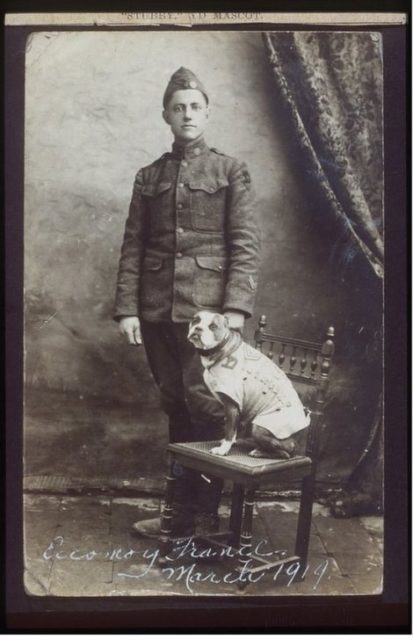

He was several weeks old and either a Bull Terrier or a Boston Terrier; in other words, a mongrel. He was friendly and affectionate. Corporal Robert Conroy was especially fond of the dog. Due to his short legs, Conroy named him “Stubby” and took him back to camp against US Army policy. As the men were happy to take care of Stubby and because he was good for the company’s morale, the camp authorities let him stay.

Stubby learned to salute officers by raising his right paw and putting it on his eyebrow. He also joined the marching routines and learned to recognize various bugle calls.

When Conroy’s company were shipped to Europe he hid Stubby in his overcoat before boarding the USS Minnesota at Newport News, Virginia. Once on board, Stubby was kept in a coal bin where he was looked after by members of the 102nd.

Their commanding officer discovered Stubby and he was not happy. However, Stubby saved the day by saluting the officer. Surprise gave way to amazement, followed by hearty laughter. He was allowed to stay. A machinist made him a set of metal “dog tags” (no pun intended) and he was given free reign of the ship.

The 102nd landed at the French port of Saint-Nazaire, and by February 5, 1918, they were on the front lines at Chemin des Dames, north of Soissons. Little did they realize what a gift they had.

The 26th Yankee Division became the most battle-scarred of America’s troops in WWI. They participated in the four major battles at Aisne-Marne, Champagne-Marne, Saint-Mihiel, and Meuse-Argonne in 17 engagements. Stubby was there for most of it.

In charge of the regiment was Colonel Henry Parker, a veteran of the Spanish-American War. So impressed was he by the recruit he gave special orders allowing Stubby to stay with the 26th.

First stationed at Neufchâteau for their training period, Conroy’s initial duties were light; delivering dispatch messages on horseback. As he was Stubby’s master, the dog accompanied him proving to be unafraid of gunfire, rocket shells, and bomb blasts.

In March 1918, he became more than just a pet. Mustard gas was thrown into their trench, and he was treated along with his two-legged comrades. Several days later, he was back in the trenches with his own gas mask. When another round of mustard gas came their way, Stubby ran around barking madly and warning the troops. He continued to warn them each time the Germans used the gas.

He was promoted to the rank of private first class on April 5. Fifteen days later, when the Germans attacked the Allies near Seicheprey, he got shrapnel in his left foreleg. Not that it kept him out of action for long; by June, he was back on the front lines.

Stubby could hear incoming artillery shells before the troops did. He whined as a signal to the men who learned to trust his keener senses, saving many from injury and death.

When not acting as an early warning system, he ran between the trenches looking for wounded soldiers. He also caught a German spy who had sneaked into their camp at night. Stubby grabbed his leg pinning him down so he could not escape until assisted by the American soldiers.

He was called “Sergeant Stubby” after that outranking Conroy. The spy had been wearing an Iron Cross which they pinned to Stubby’s army “coat” – a gift made by adoring French women.

After the war, he met with Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, and Warren G. Harding. Stubby also attended the Georgetown University Law Center with Conroy and became a lifetime member of the American Legion, the Red Cross, and the YMCA.

He was awarded nine medals including the Purple Heart.