Suleiman offered the defenders a deal. They could either surrender, and he would give them food and let them go, or they could continue fighting and all die.

Europe was at a turning point in 1522. After centuries of aggression through the Crusades against Muslims, pagans, heretics, and other Christians, the tables had been turned. The Ottoman Empire was rising to power, and had pushed deep into Europe.

The old crusading orders, including the Knights Hospitaller, were a shadow of their former glory. The Knights held the island of Rhodes, one of the last Christian strongholds in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, the Ottomans had their eyes on that land as well.

Would the last of the Crusaders stand strong and blunt the Muslim advance, or would they be crushed like so many before them?

An Unstoppable Empire?

The Ottoman Empire was a seemingly unstoppable threat to Christian Europe in 1522. They had already taken over the Balkans, and began to threaten Central Europe. They defeated the Mamluks and took over Egypt in 1517, thus gaining control over the most of the eastern Mediterranean.

A year later they took over Algeria, which gave them a convenient launch point for an attack on either Italy or Spain. However, the Ottomans knew that they could not match European navies. As a result, they began to build up their navy for both offensive and defensive purposes.

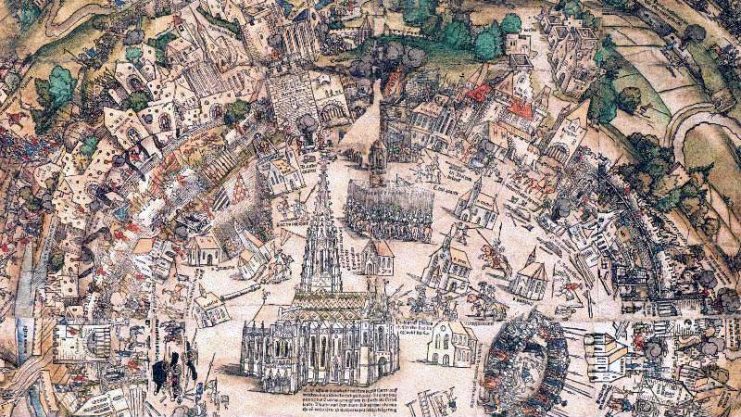

Although most Crusader States had been retaken by Muslims centuries earlier, the Knights Hospitaller, a crusading order, continued to exist. In fact, their presence on the island of Rhodes made Rhodes the last Crusader State still standing. The Knights Hospitaller had made it their headquarters after taking it from the Byzantines in 1310, who had in turn captured the island during the First Crusade.

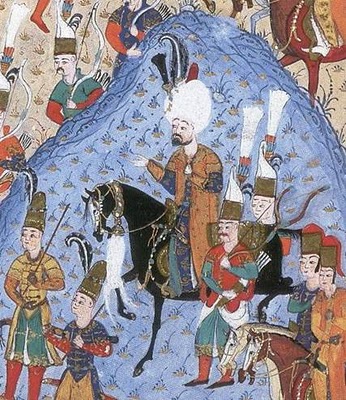

The Knights harassed Ottoman shipping, and the Ottomans knew their piracy would remain a threat unless removed. In 1520, Sultan Selim I died, and was succeeded by Suleiman “The Magnificent.” Suleiman was determined to put an end to the Knights’ presence on his doorstep.

However, Suleiman knew this would not prove easy. The Ottomans had already tried to take Rhodes once, in 1480, without success. The 1480 assault was utterly crushed despite the Muslims outnumbering the Christians probably by at least ten to one. Suleiman expected a hard fight, and prepared accordingly.

The Siege

The Knights’ fortress was incredibly well defended, and was possibly the most secure fortress in Christendom. It had multiple rings of thick stone walls on all sides except for a harbor, as well as the natural advantages of the island. The walls included protruding bastions that could be used to attack anyone approaching the walls from multiple sides.

However, there were only around 700 Knights on the island. When the Grand Master of the Order, Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, learned of the impending attack, he sent out requests for aid. However, only a small number of Venetians from nearby Cyprus joined. Rhodes had around 6,700 defenders when the Ottoman army arrived with nearly 200,000 men on 400 ships.

Suleiman himself soon arrived to directly oversee the attack. Although the Knights were badly outnumbered, they had made preparations for a siege. They had harvested or destroyed all of the wheat on the island so there would be no food for their invaders, and they placed a giant chain across the harbor so that nobody could enter it.

The Ottomans began a massive bombardment with their cannons, but the walls generally held up well. However, Suleiman had another trick up his sleeve. He brought a number of sappers, men whose job it was to dig under the walls to plant gunpowder charges.

The Knights had planned for this, too. They set up a system to detect vibrations coming from the earth, and would target tunnels before they could be used to bring down the walls. The defenders destroyed over 50 tunnels this way.

However, on September 4, after months of digging, the Ottomans successfully detonated two mines under the wall. This explosion also damaged the moat, since sections of the wall filled in part of it.

With a 12 yard (11 meter) hole blown in the wall, the Ottoman infantry launched an assault. Although they took a section of wall, a counter-attack led by Grand Master L’Isle-Adam himself forced them back. The Ottomans made several more attacks, but all were forced back.

A few weeks later, Mustafa Pasha, Suleiman’s brother and a commander, ordered an assault on another section of the wall. Pasha had been informed that this section, held primarily by Spaniards and Italians, was not as strong as others. His attack had some success, but once again, Christian counter-attacks pushed the Ottomans back. At this point both sides had taken horrible casualties in all of these assaults.

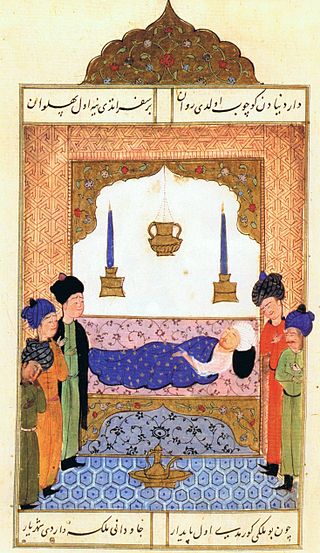

By December both sides were completely worn down. The Christians had lost the vast majority of their men, and the Ottomans had taken many times more losses. Suleiman offered the defenders a deal. They could either surrender, and he would give them food and let them go, or they could continue fighting and all die.

The defenders were willing to make a deal, but peace talks broke down. Suleiman felt that the defenders were asking for too much, and in retaliation ordered another assault. The Ottomans took the Spanish bastion once again. However, this time no counter-attack could dislodge them.

Aftermath

The defenders soon asked for peace, and Suleiman gave them reasonable terms. Suleiman allowed the surviving knights to go to Crete unmolested. For the civilians he promised protection, freedom of worship, and no taxation for the next five years. The Knights departed with their honor intact, and sailed away on ships Suleiman gave them.

The Knights and their allies had lost about 5,000 out of 7,000 men. Mainstream historians suggest about 20,000-60,000 losses for the Ottomans, although some other sources differ.

For the time being the Ottoman Empire was in control of the eastern Mediterranean, and would continue to grow under Suleiman’s skillful rule. Many Europeans responded to the Knights’ loss with fear, but their attention was soon drawn to central Europe when the Ottomans advanced into Hungary.

It was now clear that the Ottomans were a threat to all of Europe. However, the Knights would battle the Ottomans again after they eventually moved to their new home on the island of Malta. The Great Siege of Malta in 1565 would prove to be another turning point in European history.

Today the Island of Rhodes is part of Greece, and the population is predominantly Greek Orthodox Christian.