Battle Streamers are awarded to a military branch, or unit, for their participation in an important battle or campaign. They are usually earned by large groups of men and women, fighting side by side for days, months, or sometimes years. However, one of the Coast Guard’s Battle Streamers was granted for the actions of only one man.

The United States Coast Guard has always been a minority. It is the smallest branch of the US military and is spread thinly around the globe. In 1941, only one Coast Guard Officer was stationed in Manila, in the Philippines, as part of the Asiatic Squadron. Lieutenant Thomas James Eugene (TJE) Crotty, would single-handedly earn the Coast Guard the Philippines Defense Battle Streamer.

A native of Buffalo, New York, Crotty graduated from the Coast Guard Academy in 1934. He was well liked by his peers, a great sportsman, and a natural leader.

He served on a variety of Coast Guard vessels, and then took a US Navy course in mines and demolitions. On October 28, 1941, he was posted to the Cavite Naval Yard, attached to the US Asiatic Squadron in Manila.

A few months later, the world changed forever when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

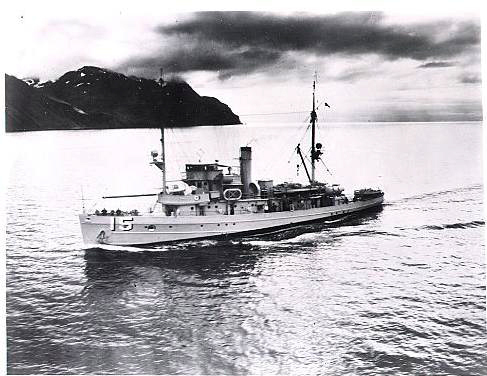

A day later, the invasion of the Philippines began. Japanese troops poured across the islands. The American forces, caught off-guard, organized a desperate defense. Two days later, on the 10th, Cavite was bombed, and the Naval Yard went up in flames. Crotty, now without a position, joined the USS Quail, an 187-foot minesweeper.

Crotty immediately became an indispensable asset to the crew of the Quail. The small minesweeper was in charge of ensuring Manila Bay remained safe. At the mouth of the bay, between Marivales and Ternate, the Americans had laid a deep minefield. They left one opening, which would often change. While this prevented Japanese ships from sneaking into the bay, it also made moving American ships more difficult.

Quail was instrumental in all aspects of the minefield. At night, motor launches manned by her crew would move mines into new formations. This allowed submarines and seaplanes which were resupplying the embattled Americans to get through. It was always done at night, with few men, to minimize detection and casualties.

Crotty, unofficially part of Quail’s crew, assisted in many of these missions, along with other officers from the ship. Crotty’s contribution to the defense went far beyond just helping.

Crotty had been stationed at the Cavite Naval Yard as a demolitions expert. He knew where every piece of ammunition on the base was, and how to get to it. Shortly after arriving on the Quail, Crotty gave this information to the Captain, and a raid was organized. The Quail steamed out from Corregidor, a fortified island at the mouth of Manila Bay, and headed for the old Navy Yard.

In a daring daylight raid, they evaded detection by enemy aircraft and snuck into the yard. They loaded their deck and stores with as much ammunition as they could safely transport, and brought it back to the defenses on Corregidor.

Almost immediately this became the new goal for every remaining ship. They carried nearly all the ammunition, and, just as importantly, rations, out of Cavite, allowing them to keep up the fight.

As the Japanese advance wore on, and the American situation became increasingly desperate, Crotty was constantly working on land and sea.

Sailors on the Quail remarked at how often this lone Coast Guard Officer would disappear for days at a time. Sometimes he went into the jungles of Bataan, other times into the old Naval Yard.

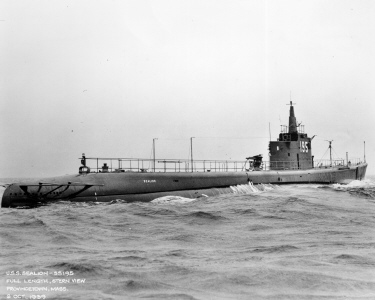

During these missions, Crotty was involved with scuttling American submarines and ships which had been docked at Cavite before the Japanese bombed it. Any vessel that could not operate was stripped of its guns and ammunition and most importantly fuel. These were then transported back to Corregidor.

The fuel was stored deep in the Malinta tunnel. The guns and ammunition were placed at strong defensive points around the small island. The Americans knew the Japanese forces would soon be there to take their island fortress, and they were not going to go quietly.

With Crotty’s aid, the Marines, sailors, and soldiers who made up the defense in Manila were able to fortify themselves in the mouth of the bay and wait out the battles on the mainland.

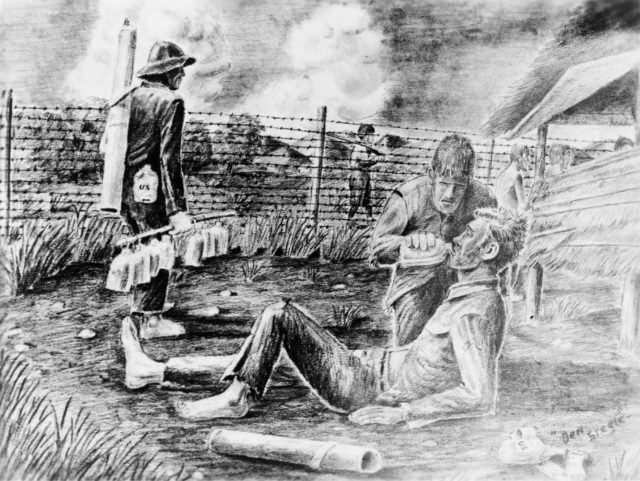

Crotty also assisted in the defense of Bataan. American troops had been putting up a stiff resistance against an intense Japanese attack for months. The young Lieutenant went ashore and helped the Naval Battalion.

The Japanese had circled around Bataan, landing troops at points behind the American line. This gave them the possibility of cutting off the Americans from Corregidor, and force a surrender.

However, a Naval Aviator, Commander Francis Bridget, created a force of 500 rear echelon and Naval troops. With some Marine infantry along with Filipino infantry, these men were able to halt the Japanese advance at their beachheads, preventing the complete collapse of Bataan for months.

Crotty went ashore to aid Bridget with his defense, providing his troops with supplies. Eventually, the two men retreated to the Quail, to bombard Japanese positions on shore. Thanks to Crotty and Bridget, the small ship, with 1917 dated ammunition, and only two guns was able to account for the deaths of 140 Japanese soldiers and the destruction of most of the Japanese supply dumps.

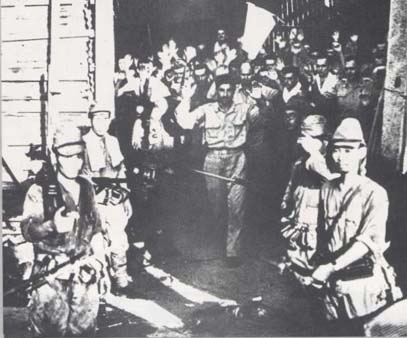

On April 1, 1942, Crotty sent his last letter home, and on the 9th, he was permanently transferred to Corregidor. By May 5 he saw action again, this time commanding a Marine gun battery.

The Japanese had landed on Corregidor, threatening the remaining American troops there. On Malinta Hill, he kept the guns firing down towards the Japanese beachheads, in a desperate attempt to prevent a total defeat. Sadly his guns were finally silenced, and he became a prisoner, He was the first Coast Guard POW since 1812 when sailors in the Revenue Cutter Service had been captured by the Royal Navy.

Lieutenant Commander Denys Knoll, a Naval Intelligence Officer, spoke highly of Crotty. In a letter to Russel R. Waesche, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, he praised the young Lieutenant’s high morale, kind spirit, and willingness to fight.

He knew the horrors the men on Corregidor and Bataan had undergone. He believed that if Crotty could survive that, he would be able to endure any pain or terror in a POW camp. This prediction was sadly short lived.

Shortly after arriving at the now infamous Cabanatuan prisoner of war camp, Crotty came down with diphtheria. Hygiene in the camp was nonexistent, and there was little anyone could do to protect themselves from this horrible epidemic.

Thomas James Eugene Crotty, Lieutenant, US Coast Guard, died on July 19, 1942. His actions on the Quail, at Bataan, and Corregidor were lost to memory for decades. His determination and quick thinking had undoubtedly aided the valiant defense of Manila Bay from the Japanese attackers.

His actions from December 1941 to May 1942 single-handedly earned the United States Coast Guard the Philippines Defense Battle Streamer; a feat unmatched in the service’s history.

For his bravery and skill in combat, he was awarded the Bronze Star, along with the Purple Heart. Tragically, the whereabouts of his remains are unknown.