The Slovak National Uprising was part of the Czechoslovak antifascist resistance during World War 2 and the most important period in the history of the Slovak nation.

It started on the 29th of August 1944 and lasted for two months until it was partially suppressed and transformed itself into a guerilla war. Besides Slovaks, there were members of 32 other nations, coming from four continents, that joined the struggle and fought elite Waffen-SS units.

Events that preceded the Slovak National Uprising

During the interwar period, Czechoslovakia was a democratic “island” in Central Europe with strong ties with France, Britain, and the United States, until it was betrayed by its allies and lost parts of its land to Nazi Germany, Poland, and Hungary. The country ceased to exist by March 1939, after Slovakia and the Subcarpathian Rus proclaimed their independence and Czech lands were invaded by Nazi Germany.

Subcarpathian Rus and Slovakia were subsequently invaded by Hungary, but Slovakia managed to defend its independence. It became a satellite state of Nazi Germany, a de facto vassal that even fought against other Slavic nations in Poland and the Soviet Union. Slovakia sent tens of thousands of its Jewish inhabitants into death camps, and it became the only country in history that paid Nazis to murder them.

Czechs, Slovaks, and Rusyns, who had fled their homeland, formed military units in France, Britain, Yugoslavia, Palestine, Libya, and the Soviet Union, and fought on the side of the Allies. Czechoslovak antifascist resistance was organized by the Czechoslovak exile government in London.

By 1944, it became clear that Czechoslovakia would be liberated from the east by the Red Army. Therefore, the Slovak Lieutenant Colonel Ján Golian was appointed as the main organizer of an armed resistance inside Slovakia that would overthrow the local fascist government and support the Red Army advance.

Members of the Slovak Army were sick of the war with other Slavic nations, and many of the officers were loyal to their true homeland, Czechoslovakia.

Preparations for the armed resistance in Slovakia

Organizers of the armed resistance prepared two plans.

The Offensive Scenario worked with the idea that the armed resistance would start when the Red Army captured the Polish city of Krakow. Slovaks would rise up, seize power, and help the Red Army penetrate the Carpathian Mountains, thus creating a third main battlefront right after the two main ones in Poland and Hungary.

The Defensive Scenario worked in a situation where Slovakia would be invaded by Nazi Germany, as happened in Hungary in March 1944. In the case of such an invasion, Slovaks would create a defensive perimeter around the heart of the Uprising, the beautiful town of Banská Bystrica, and they would hold out until the arrival of the Eastern Front with its Red Army and the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps formed in the Soviet Union.

The armed resistance also had its material organizers that formed themselves around the Governor of the Slovak National Bank, Imrich Karvaš, and member of the parliament, Peter Zaťko.

Both established a network of anti-fascists that managed to block Slovak gold reserves and move 3.5 billion Slovak crowns, 1 million liters of gasoline, 20 thousand pairs of shoes, large amounts of wheat, flour, legumes, vehicles, tires, and other important goods into Central Slovakia for the use of the armed resistance.

At the same time, military organizers were filling storages in Central Slovakia with weapons, ammunition, and other military materials. This went on without anyone even noticing what was going on. Ján Golian created a network of antifascist officers that was ordered to seize power and engage Axis forces, according to one of the scenarios.

By this time, the Slovak economy was already on its knees and the country was trading only with Nazi Germany, Switzerland, and Sweden. Nazi Germany got its hands on all key Slovak industries. It owed Slovakia 7 billion crowns and sucked the country dry through an unfavorable exchange rate.

Slovaks were on ration cards with shortages of goods. The country was paying its investments and welfare programs by printing out more money, having a twofold increase of currency in circulation and thus causing high inflation. Wartime boom was going down, and information about horrific Nazi war crimes committed in the Soviet Union and Poland were coming in. People had had it with their government and were willing to fight their way out.

The Soviet Union had valid agreements with the Czechoslovak exile government in London and was obliged to support its ally and ensure that Czechoslovakia would be re-established within its pre-Munich borders, i.e. prior to the Munich Agreement of 1938.

Slovaks in Slovakia and Czechoslovaks in London were seeking Soviet help regarding the upcoming Uprising, but the Soviets were silent. They were simply not interested in helping democratic forces gain power in their country because they wanted the country to turn red, adopt communism, and become its satellite within a new bipolar world.

By this time, Czechoslovakia was already falling within the Soviet sphere of interest. Military help coming from the West would be blocked, including two airborne brigades that were to be deployed to support the Uprising.

Flame over the Carpathians

Slovakia was invaded by Nazi Germany on the 29th August 1944, forcing insurgents to follow the Defensive Scenario and defend the mountainous central parts of Slovakia until the arrival of the Eastern Front. The situation looked bleak and the Slovaks had to deal with one crisis after the other.

SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger was entrusted with the invasion of Slovakia, and he was so confident in his mission that he proclaimed that the Uprising would be defeated within days. This wouldn‘t happen, so on the 19th September 1944, he was replaced with SS-Obergruppenführer Hermann Höffle, who took part in Hitler’s Munich Putsch in 1923.

At the end of the war, the war criminal Gottlob Berger would be taken prisoner by Americans and sentenced to 25 years in prison at the Nuremberg Trials, but he would be released in 1951. Hermann Höffle would be tried for war crimes in Bratislava and hanged in 1947.

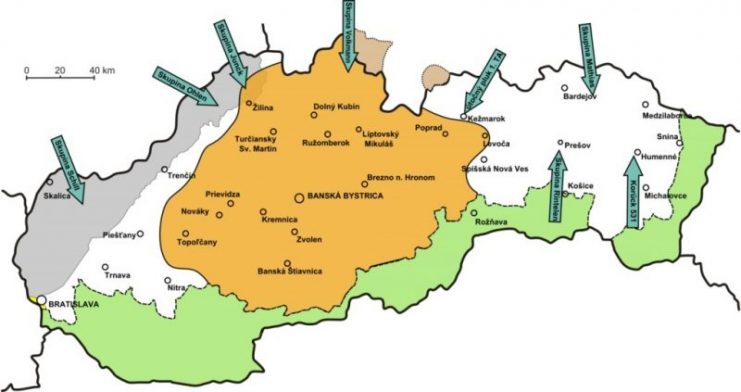

Germans started entering Slovakia from all directions, except the south so as not to make it look like Hungarians had something to do with the invasion, which would definitely lead to a stronger Slovak resistance.

Group of Colonel Conrad von Ohlen and Group of Colonel von Junck attacked the town of Žilina. SS Kampfgruppe Schill captured Bratislava and continued its advance onto Nitra. Kampfgruppe Volkmann attacked the Orava region from the north. SS Kampfgruppe Schäfer was advancing towards the Liptov region in the north, and the Assault Regiment of the 1st Tank Army was advancing through Poprad towards Banská Bystrica.

In the meantime, Germans performed Operation Kartoffelernte mit Prämie (Potato harvest with bonus) where they disarmed a major part of the Eastern Slovak Army, which was building defensive positions for Axis forces in Eastern Slovakia. Its members were interned in Germany. The Germans did not trust Slovaks with weapons in their hands anymore because thousands of them changed sides while fighting on the Eastern Front.

In this way, the Uprising lost its strongest fighting force. There were several reasons for that, but the most important one lay, once again, in the Soviet Union, which was not willing to take control of and utilize the Eastern Slovak Army; at the same time, the Soviets were not eager to say it out loud. They played the dead beetle until it was too late.

Insurgents formed the 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia, the largest military force of the Czechoslovak antifascist resistance in World War 2. At first, the Army consisted of men from local military garrisons, but after the first mobilization wave of all men under the age of 35, their numbers grew to 47,000. By the end of September 1944, the second mobilization wave of all men under 40 made its numbers rise to 60,000 men. The number of partisans grew to approximately 12,000.

Insurgents did not have weapons for one-quarter of their men, and they lacked tanks, anti-tank weapons, planes, and anti-aircraft weapons. The Germans, on the other hand, were well-armed, had heavy weaponry, and total aerial superiority.

As the frontlines were moving, the captured areas were pacified by special SS commandos that murdered civilians, burned villages to the ground, and were finishing the so-called Final Solution of the Jewish Question. Until the end of the war, these forces would murder over 5,000 civilians and send 13,500 racially persecuted people into extermination camps to their certain death.

The second largest mass murders happened next to the village of Kremnička, and the area was littered with mass graves that consisted of 747 bodies. When the soil froze, people were murdered in the lime factory in Nemecká with conservative estimates of 900 murdered people. Sadly, even fascist Slovaks were taking part in murdering their own.

The 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia was able to stabilize frontlines, determined to hold out as long as it would be necessary. It was supported by the American group from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was the predecessor of the CIA. The OSS Mission was led by Lieutenant James Holt Green, hero of the Slovak National Uprising, who cooperated closely with Ján Golian.

The OSS Mission gathered lots of valuable intelligence for the Allies. They also managed to get Allied aviators who were captured in Slovakia into safety, unofficially bring 24 tons of military materials for the Uprising, and support the struggle by directing strategic bombardment missions onto enemy targets.

The majority of the OSS Mission was later captured and murdered by Nazis in the Mauthausen concentration camp, including the only Allied war correspondent executed by the Axis during the war, Joseph Morton.

In comparison to the unofficial 24 tons sent by Americans, Soviets provided the Uprising with only 639 tons of military materials. When compared to American military help to other antifascist groups in Europe, Soviet military help for Slovaks was less than symbolic.

The most important help that came from the Soviet Union were 21 Lavochkin La-5 fighter planes with Czechoslovak pilots from the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Fighter Regiment that were deployed in the Uprising, and parachutists from the elite 2nd Czechoslovak Airborne Brigade that took part in the final stages of the Uprising and acted as its most valuable fighting force.

Nevertheless, even these deeds were sabotaged by the Soviet Union, which wanted nothing less than a servile communist Czechoslovakia and they succeeded in 1948 with the February communist coup.

As the area of the Insurgent Territory was decreasing, parachutists from the Airborne Brigade were acting as a mobile reserve of the 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia. They were deployed into the most critical sections of the frontline, stopping every enemy advance.

The 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia changed commanders with the arrival of the only Slovak interwar general, Division General Rudolf Viest, while Ján Golian became his deputy. Rudolf Viest was highly respected and skilled, which helped to prolong the Uprising.

German General Offensive

The end of the first phase of the Uprising came with the German General Offensive, that started in the second half of October 1944. Germans were strengthened by the 18th SS Volunteer Panzer Grenadier Division Horst Wessel, SS Sturmbrigade Dirlewanger (notorious for its war crimes during the Warszaw Uprising), 14th SS Volunteer Waffen Grenadier Division Galicia, and SS Kampfgruppe Wittenmayer totaling up to 50,000 skilled and well-armed men.

Germans started to push the insurgents from all directions. The 18th SS Volunteer Panzer Grenadier Division Horst Wessel played the most important part in the Offensive. The 18th Division divided itself into three groups and used two of them to attack two southern sections of the frontline.

When insurgents moved their reserves to slow down enemy advances in all directions, the largest group of the 18th Division attacked the town of Detva and captured the town of Zvolen, just south of Banská Bystrica.

After two months of fighting, while being surrounded by the enemy, the 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia was in a state of total decay and de facto stopped existing. SS Kampfgruppe Schill became the first enemy unit to enter Banská Bystrica at 6:30 AM on the 27th October 1944.

The Slovak National Uprising was partially suppressed, but insurgents did not surrender. They fought on in the mountains until they helped the Red Army, Romanian Army, and 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps advance through Slovakia and liberate the land.

Due to Soviet failures in connection with the Uprising, 63,000 members of the Red Army and 11,000 members of the Romanian Army were killed in action while liberating Slovakia in 1944 and 1945. Politics simply had more value than human lives.

Read another story from us: Conflicting Alliances – The Liberation of Prague, 1945

Unfortunately, both commanders of the 1st Czechoslovak Army in Slovakia, Brigade General Ján Golian and Division General Rudolf Viest, were captured by the enemy and murdered. After the February 1948 communist coup, the role of these generals was defamed, and Czechoslovakia entered a four-decade-long period of spreading lies about the Czechoslovak antifascist resistance during World War 2. What’s even worse was that many war heroes who fought in France, Britain, Africa, the Soviet Union, and the Royal Air Force were persecuted, imprisoned or even murdered by the regime.

Vladimír Olej is the author of the novel The Corner of Death, which tells the story of a Slovak female medic who changed sides on the Eastern Front and took part in the Czechoslovak antifascist resistance. The book is filled with interesting historical data, and it tries to set things straight and tell the stories of Czechoslovak war heroes.