The modern view of Buddhism is one of a peaceful, highly spiritual faith, where the devotee sets out upon the path to enlightenment through meditation and discipline. But the sohei of feudal Japan were anything but peaceful.

Sohei means ‘warrior monk’. They came into being in the early middle ages, as differing sects of Buddhism ultimately took up arms against each other. They were a major political force in Japan, terrifying not only because of their prowess in war but also because they carried immense spiritual authority, bringing down curses upon any who displeased them.

Their overall effectiveness can be summed up in the words of the 12th-century emperor Go Shirakawa-In: ‘There are three things that are beyond my control: the rapids on the Kamo river, the dice at gambling, and the monks of the mountain.’

Sohei Equipment

The equipment of the sohei differed little from that used by samurai. They wore the usual kimono and broad trousers. Their garments were usually white or saffron.

They used traditional samurai armor – the do, of lamellar iron construction, with long ‘skirts’ protecting the upper legs. A dark jacket would usually be worn over the armor.

Monks were instantly recognizable because they wore a white headcowl over their shaved heads, wrapped around until only the eyes were exposed. Some, but not all, wore helmets.

The most popular weapon in the warrior monk arsenal was the naginata, a vicious glaive-like polearm that they wielded with great proficiency. They also carried katana (swords) and tanto (daggers) tucked into the belt. Many sohei were expert archers.

Distinguishing features included the headcowl, and most monks wore wooden rosaries around their necks. Many warrior monks wore geta (wooden sandals), although these would have been impractical in a fight, so whether they wore them in battle is debatable.

When on campaign, sohei carried a mikoshi (portable shrine) around with them. This in itself was daunting to their foes, for to enact violence in the presence of such a holy item was blasphemous in the extreme.

Sohei Organisation

Warrior monks were loyal to their temple. Some of the most famous (or notorious) were the sects of Negoroji, Nara, Miidera and Mount Hiei. Most of the infighting between rival sects was not secular in nature: almost all violence had its roots in politics. In this, the wars of the sohei differed markedly from the religious strife of medieval Europe.

The backing of the sohei could spell the difference between victory or defeat in a conflict. Many samurai warlords loathed them, branding them akuso (evil monks), whilst others fearfully curried favor with them.

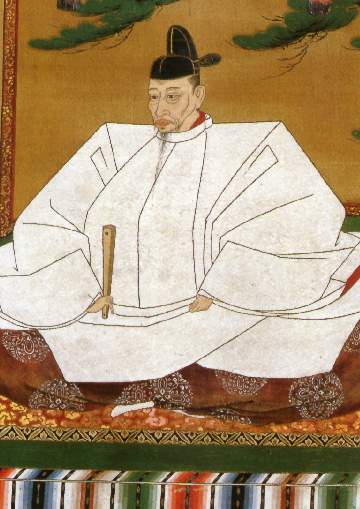

Oda Nobunaga, one of the great generals who put Japan on the path of unification, had particular reason to hate them. The monks of Mount Hiei became the allies of the Asai and Asakura families, some of Nobunaga’s biggest rivals. Nobunaga defeated them in battle in 1570, but they struck back later that year.

Defeated by Nobunaga’s general, Toyetomi Hodeyoshi, they fled into the mountains and were saved by the sohei of Mount Hiei. Weary of their interference, Nobunaga launched a campaign against the monks in September 1571, completely destroying the temple complex of Mount Hiei and massacring every man, women, and child – in all, over twenty thousand people.

Nobunaga detested the sohei and mounted a number of campaigns against them, all resulting in heavy slaughter. As Japan gradually came under a single unifying influence – first Nobunaga, then his successor Hideyoshi, and finally Tokugawa Ieyasu – the last centers of independent sohei authority were brought to heel. The days of the warrior monks were over.