Before and during WWII, or “Great Patriotic War” as it is known in the nations that made up the USSR, the Soviets built tens of thousands of tanks, artillery pieces, and planes. Most of those planes were fighters, but it might surprise you to learn that a large number of them are listed as bombers, at least according to the statistics of Oxford Companion to WWII compiled by noted historians I.C.B Dear and M.R.D Foote.

However, statistics can be misleading, for when people in the West think about WWII bombers, they think about American B-29’s, -17’s, and -24’s, and British Stirlings, Halifaxes, and Lancasters. All were large in size, carried a large payload, and traveled a great distance.

The Soviet Union, for a variety of reasons having to do with strategic and tactical doctrines, politics, and economics, eschewed the large bombers of the Western Allies for smaller dive bombers and fighter-bombers. These are the “bombers” listed in their production reports. The most famous Soviet bomber was the Ilyushin Il-2 “Sturmovik,” one of the best tank-killers of the war, but hardly a strategic bomber.

For that reason, it comes as a surprise to many to find out that the Red Air Force actually carried out strategic bombing raids on Berlin, shortly after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in late June, 1941.

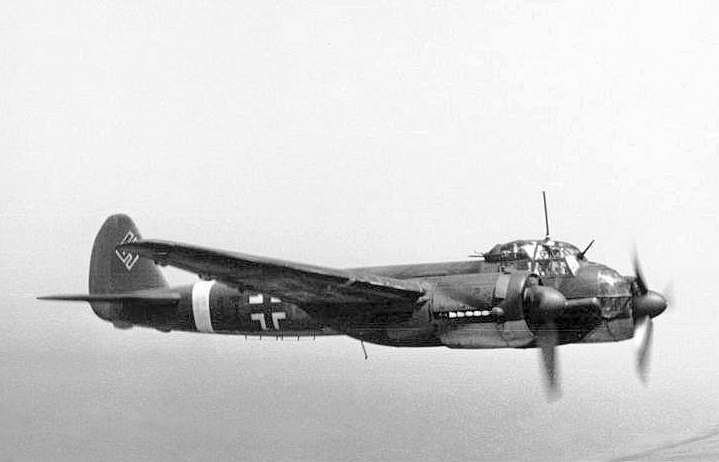

By July, the Germans were close enough to the Soviet capital, Moscow, that they could begin bombing raids on the city. Junkers 88’s, Heinkel 111’s and Dornier 17’s rained high explosive and incendiary bombs, but though they did a significant amount of damage to the city, the destruction never reached the levels of the Allied bombing campaign against Germany in the latter half of the war. The Germans were also surprised by the heavy anti-aircraft defenses ringing the Soviet capital.

The physical damage was still significant, but what worried and angered Stalin most was the potential psychological damage done by the Nazi raids. In a nation already being invaded, and whose army was taking blow after blow on the front lines, the raids could prove to be catastrophic to morale. And in a nation that had also suffered greatly under Stalin’s purges of the 1930’s, political turmoil likely worried the Soviet leader most.

For that reason and others, the dictator ordered Berlin bombed immediately. To that end, the Red Air Force established a bomber base at the airfield at Pushkino, near Leningrad (St. Petersburg). They also used an island base off the coast of Estonia at Osel, now known as Saaremaa.

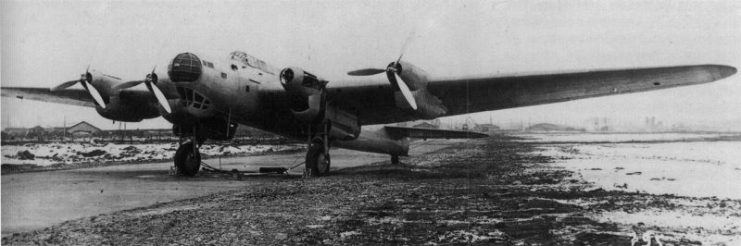

On August 7, 1941, 15 Ilyushin DB-3 bombers headed across the Baltic Sea, reaching the German city of Stettin (today Poland’s Szcezin), and then flew southwest the 93 miles to Berlin.

The DB-3 was designed in the early 1930’s and built from 1936-39. By 1941, like the other large bombers in the Soviet fleet, the Petyakov Pe-8s, they were obsolete. They looked it. Incorporating the new Soviet art deco style of the 1930’s when designed, they were impressive – to look at. But effective bombers? No. Many times, for example, when the Pe-8 took off, the gunners of its 11 man crew made their way to their positions in pods on the wings – by walking to them while in flight.

The DB-3 was roughly the same size as the American B-25 Mitchell tactical bomber. It had a crew of three, a maximum speed of 273 miles per hour, a ceiling of 31,000 feet, and a theoretical range of 2,300 miles–this was for an empty, stripped-down plane, since the Soviets always padded their statistics. The crew defended the plane with 3 7.62mm machine guns, although the last version was outfitted with a 20mm cannon, and up to 5,000 pounds of bombs.

Hermann Göring had famously declared that no enemy bombs would fall on Berlin. If they did, Germans could call him “Mayer,” a nickname for a stupid, ignorant yokel. By 1943, many Germans secretly referred to him as “Field Marshal Mayer.” In 1941, however, Göring’s boast still carried weight. Berlin was teeming with anti-aircraft defenses.

Virtually all of them pointed west, because it was expected that any air attacks launched on Berlin itself would come from England. The few prior air raids that had been mounted against Berlin had been British. Not on July 7.

Fifteen Soviet bombers took off from Osel in the middle of the night. Berlin was lit up like a Christmas tree – at that point in the war, mainly for morale reasons, the Germans did not practice blackout precautions in their capital and other major cities. Of the fifteen bombers, five found the target – Soviet long-range navigation, and to be fair, that of the other western Allies in the beginning, was not that good.

Still, those five planes flew over perplexed anti-aircraft defenders who actually flashed searchlights in the air – not to spot the planes, but flashing codes like “Who are you?” and “From where did you take off?.” They thought that these were German planes that had neglected their duty. The other Red Air Force planes bombed Berlin’s tony suburbs and the coastal city of Stettin.

Did the bombs do any significant physical damage? Not really. But like the American Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in April 1942, they did have a significant psychological impact. Not so much in Germany, though the idea that Soviet bombers could get through when German troops were almost at the gates of Moscow did anger both Hitler and Göring and temporarily shocked the German public.

However, the Soviet press and propaganda machine played up the raid, which did affect Russian morale. “Though the Germans are driving, we’re still in the fight” the raid seemed to say.

Read another story from us: Amazing Photos of the Fall of Germany 1944 – 1945

The raids of August 7 were followed up by more raids which were not so effective. The Germans were now ready for raids coming from the north and east, and eighteen Soviet bombers were shot out of the sky. In early September, the Nazis overran the Osel Island base, which ended Soviet raids on German soil until the end of the war.