Their presence was vital to protect these heavily laden and incredibly valuable ships from attack by foreign powers and pirates.

Emerging in the mid-16th century, the Spanish galleon quickly became hugely important both to naval warfare and to securing civilian trade from the Americas. It remains one of the most influential warships in history.

The Evolution of the Galleon

Though its exact origins are uncertain, the galleon design combined distinct features of ships from the Mediterranean and northern Europe – two regions in which the Spanish found themselves fighting.

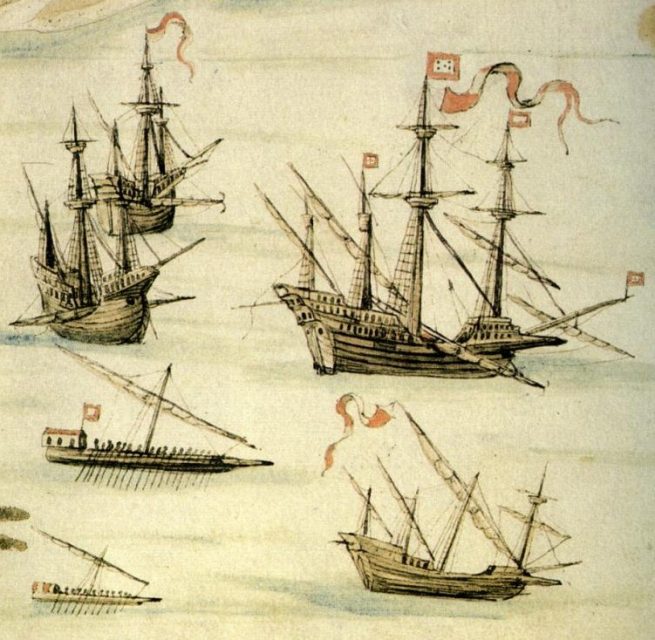

In the Mediterranean, oared galleys were common as fighting ships, and by the early 16th century these carried cannons at the front. They also made use of lateen-rigged sails. They were good for fighting in relatively still waters but lacked the stability for ocean voyages.

In the North Sea and North Atlantic, admirals were fielding increasingly large carracks. Like galleons, these high-sided, square-rigged sailing ships had been in use for centuries. They could survive storm-tossed seas and provide a fighting platform for both men and guns.

The first galleon can arguably be dated to as early as 1517, but it was in the 1530s that the design and its name became common. With a mix of sails, high aftcastle, low forecastle, and ports in its sides from which cannons could fire, it could handle trans-Atlantic voyages as well as fierce sea battles. It, therefore, filled a vital role for the Spanish, protecting their growing treasure fleets as silver and gold flowed back from their colonies in the Americas.

Shipbuilding

Spanish galleons were mostly built in two distinct regions – the Basque country and southern Andalucia. As Spanish power increase in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, shipbuilding also took place in territories engulfed by the Spanish empire, including Portugal, Flanders, parts of Italy, and the Caribbean.

Construction was usually carried out by private shipbuilders following tight regulations laid down by the government. Mathematical principles and practical experience let shipwrights build a large number of increasingly larger ships in line with these rules.

They were paid in installments at specific stages of the work, before handing the ships over to the crown once completed. Royal officials would then arrange for the ships to be outfitted and decorated as ready to sail.

Armaments

The production of ships’ guns and ammunition was even more tightly controlled. Guns, powder, and shot were all produced in royal foundries and workshops. Private contractors weren’t even allowed in on powder production until 1633. When guns ran short in the late 16th century, some were imported from abroad.

The guns came in a range of different lengths and calibers, each with their own type of shot. They were generally longer than the guns used on English ships and were often the sort of field pieces also used on land. This made it harder, slower work to move the guns back and forth for loading and firing in the confines of the ships.

Over time, lessons were learned and more appropriate barrels and carriages were developed, but in times of high demand, such as the equipping of the Armada, every sort of available gun was taken to sea.

Operation

Galleons served in two main roles.

First, there was the protection of the flotas, the fleets bringing treasure back from the Americas. Galleons on these runs would usually transport one fleet west across the Atlantic and then pick up a different fleet to escort home.

Their presence was vital to protect these heavily laden and incredibly valuable ships from attack by foreign powers and pirates – both freelance buccaneers and those supported by the English in their unofficial naval war against Spain. The trips by these galleons were funded by the averia, a tax on ship owners meant to cover the protection they received.

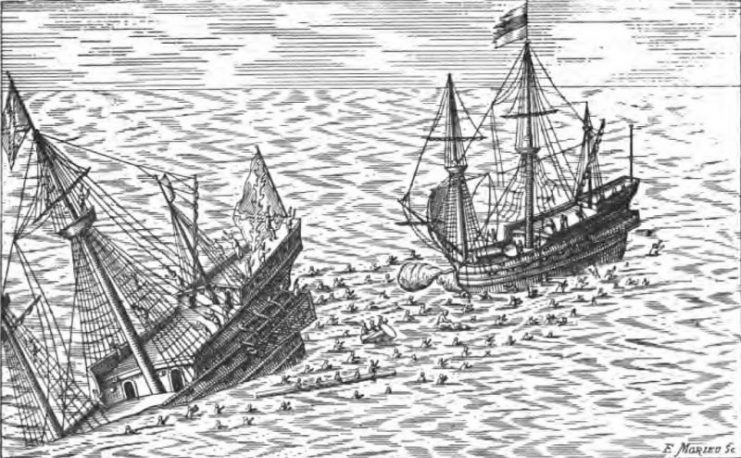

The other use of galleons was in war fleets. The Spanish fought on a number of fronts during the 16th and 17th centuries, launching campaigns against Islamic powers and Barbary corsairs in the Mediterranean, against Protestant rebels in the Low Countries, and against the endlessly bothersome English and their privateer fleets. These sometimes required powerful fleets that packed a punch as well as carrying ground troops, and for this work, the galleon came into its own.

Life Onboard a Galleon

Galleons were crowded full of soldiers, sailors, gunners, officers, and other crew and passengers. Space was at a premium. Most of those onboard slept crammed in together either below or on deck. The most senior officers got private cabins, while others of rank gained some privacy by setting up curtains or wooden screens.

The crew worked in three watches, each taking two four-hour shifts a day. The changes of watches and other significant moments in the day were marked with prayers and religious chanting. Meals were generally eaten around shift changes and consisted mostly of wheat biscuits, beans, pulses, and rough red wine, with salted beef or fish depending on supplies and the day of the week.

With so many men crammed in together, conditions became smelly and unhygienic. Rats were a serious problem, attacking food supplies and any animals on board. Other vermin such as cockroaches, mice, scorpions, and fleas added to the discomfort.

The Galleon at War

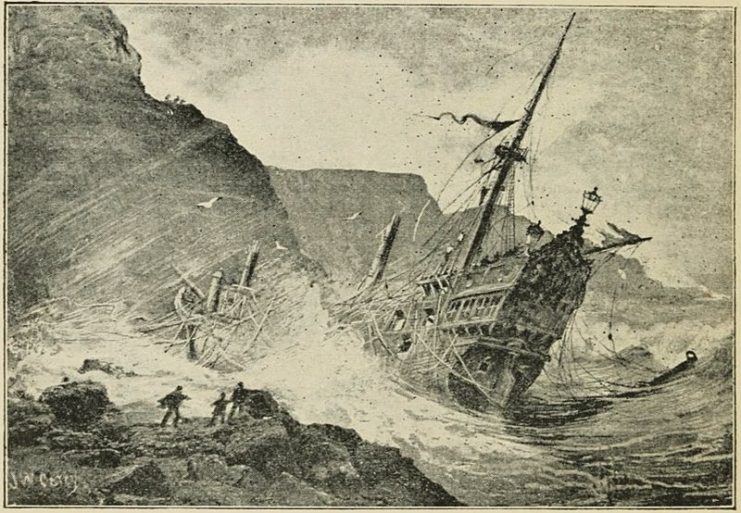

For most of the 16th century, the Spanish clung to an old-fashioned model of naval warfare in which most of the damage was done through boarding actions. Guns were used just for preliminary bombardments and few shots were fired compared with some other navies. This was still the case as late as 1588 and played a part in the disastrous failure of that year’s attempted invasion of England.

Read another story from us: Sunken Treasure: The Fight Over the Spanish Galleon San Jose

Following the Armada, more emphasis was put on gunnery. Galleons carried a fearsome weight of guns and could devastate enemy ships. But mismanagement led to repeated disasters against better-led fleets such as those of the Dutch.

The Spanish galleon was a deadly weapon that helped ensure Spain’s place as a leading world power. But any weapon was only as effective as the men wielding it, and the rise of British and Dutch naval power was made possible by Spanish commanders who failed to capitalize on the galleon’s potential.