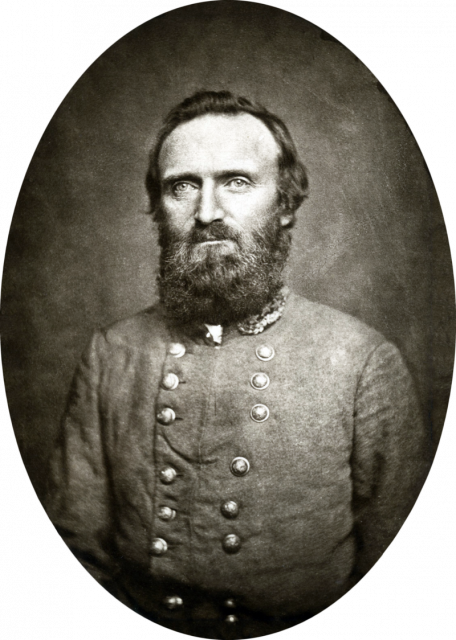

Though his participation was cut short, Rebel General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson proved a skilled tactician and trusted compatriot of fellow Rebel Robert E. Lee.

Like Lee, and their opposite at the fateful battle where Jackson lost his life, George McClellan, Jackson served the United States in its war with Mexico, where his bravery under fire reflected his future Rebel gravitas, and also his eventual demise.

Before his participation in the Mexican-American War, Jackson, having graduated West Point, engaged in frontier duties as a brevet Second Lieutenant of artillery. His time on the frontier facing hostile natives gave him practical but limited experience on horseback under fire, another skill that would serve him well in his brief career.

Eventually, Jackson found himself transferred to the Rio Grande as part of the First Regiment of Artillery, where he was put in charge of overseeing the transport of guns and mortars to various forts protecting Port Isobel.

With the Texas frontier more or less stable, Jackson found himself away from combat with little prospect of an invasion through northern Mexico to Mexico City. However, Major General Winfield’s Scoot planned invasion of Vera Cruz, from which he would march to Mexico City, required the bulk of the troops stationed at the Rio Grande. Jackson, along with the First Regiment of Artillery, joined the General as his army sailed southward.

At Vera Cruz, Jackson’s unit faced continual action, the regiment’s heavy guns were put to good use to take the city. His calmness under fire earned the notice of his commanders, and Jackson was promoted to First Lieutenant of Volunteers “for gallant and meritorious conduct at the siege of Vera Cruz.” Having secured a beachhead, General Scott’s army marched on to Mexico City.

Along the way, the General’s forces faced continued Mexican resistance. The First Regiment of Artillery found itself in the roll of infantry for the Battle of Cerro Gordo of April 18. After the battle, Jackson was offered the chance to serve with a captured Mexican battery. Jackson, partial to the beauty of the bellow of blast, eagerly accepted the posting to Magruder’s Battery.

His new position secured, Jackson and the rest of the US Army continued the march to Mexico City, engaging the Mexicans between them and the enemy capital. Jackson himself would face little direct action until the assault on Chapultepec, the mighty fort anchoring the defense of Mexico City where many future Civil War generals –and the United States Marine Corps- distinguished themselves.

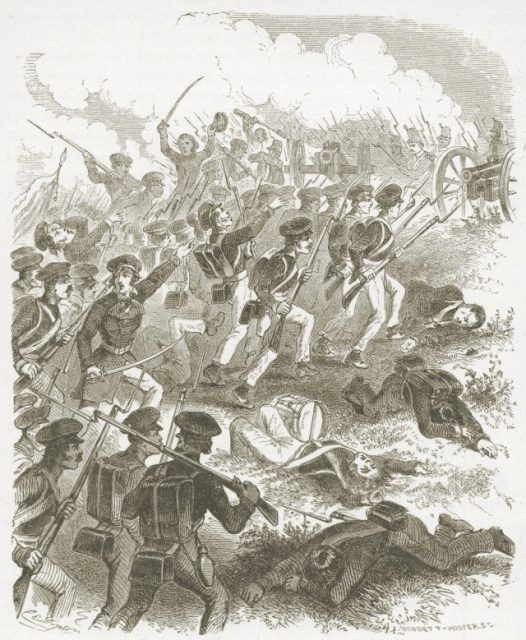

Magruder’s Battery was attached to Major General Gideon Johnson Pillow’s prong of the assault, where it found itself under heavy fire from Mexican artillery.

Placed in a causeway and with the enemy artillery well protected by breastworks, the battery started to route in the face of such intense bombardment. Jackson, perennially calm under fire, hauled a small fieldpiece into a new position to try and take out the enemy artillery.

While enemy guns blasted all around him –one shot even landing between his legs- he endeavored to rally the remains of his battery, but they had already fled. Jackson was given orders to withdraw, but argued that retreating would be more dangerous, and, if given fifty veterans, he could storm the breastworks and silence the defensive artillery.

With only a sergeant to aid him, Jackson proceeded to return fire on the Mexicans with his lone fieldpiece. Another gun was eventually manhandled into position, and the battery, no doubt inspired by Jackson’s courage and seeming immunity to enemy artillery, rallied.

In due time the breastworks fell, the castle stormed, and the city taken. For his bravery under fire, General Scott personally praised the young officer, promoting him to the brevet rank of Major for his heroic actions. Jackson, amusedly, seemed not fully aware of the full extent of his actions until long after the city fell.

While the dust settled, Jackson met a fellow southern officer by the name of Robert E. Lee, and the two would be close associates until Jackson’s death.

After the war Jackson pursued military academics. Teaching at the Virginia Military Institute, when the state seceded from the Union, the future Stonewall joined his fellow southern officers in fighting for the rebellious states.

Jackson’s courage would earn him his Civil War nickname, and, combined with the fog of war, bring about his death. Ironically, though well versed in artillery, Jackson would find himself in command of infantry, his love for action outweighing his adoration for well placed artillery. Had he stuck with his original profession, he may well have survived the war.