During WWII, the US Army and its justice department dealt with many offenses carried out by the men in their ranks. From petty theft to rape and murder, life on the frontline sometimes caused soldiers to turn to crime for personal gain.

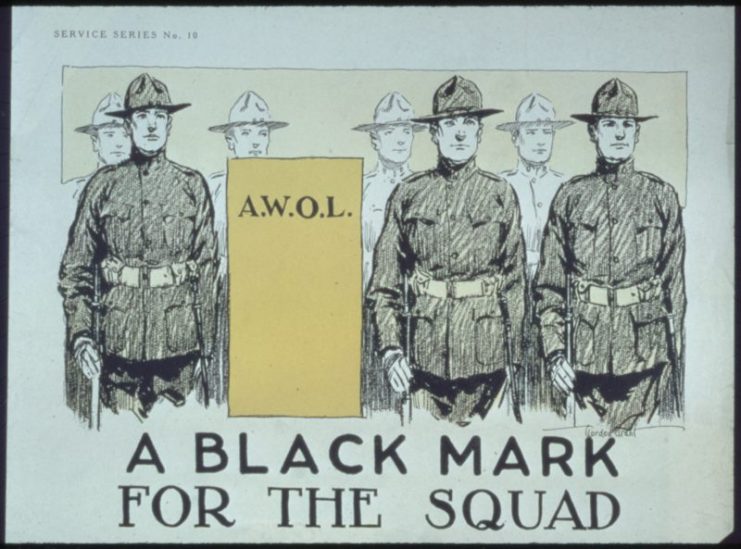

But the army also had another problem ― one that was much more common during wartime ― desertion. Around 21,000 American soldiers faced charges for desertion, and 49 of those were given severe sentences. Out of those 49 soldiers who were sentenced to death, only one was executed. His was the first death sentence for desertion that was carried out since the American Civil War.

His name was Eddie Slovik.

Slovik was a troubled youth and was frequently arrested as a minor. At 12 years of age, he was arrested after he had broken into a foundry with several accomplices to steal brass to sell on the black market. Between 1932 and 1939, he was apprehended several times for crimes such as petty theft, breaking and entering and disturbing the peace. Slovik’s last adventure into disobeying the law during peacetime happened in 1939 when he and a few friends stole a car and crashed it while extremely intoxicated.

Having spent three years in jail, Slovik was paroled in 1942. He found a job in a plumbing company, married and sort of backed down from his turbulent life. As he had a criminal record, he was at first classified as unfit for duty by the authorities. But as the war progressed and the US Army was in need of fresh recruits for the invasion of France, Slovik was reclassified in January 1944 and drafted.

In August he was sent to join the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division in France, as part of a 12-man replacement detachment. En route to his unit, somewhere in France, he was met by an enemy artillery barrage. It was his first encounter with the reality of war, and his first instinct was to hide. Together with a friend he had met in basic training, Slovik found refuge in an improvised cover. As a result, the two men became separated from the rest of the detachment.

It was there that he witnessed the true horror of war. Later, he stated that his christening in the barrage of fire was the moment when he realized that he “wasn’t cut out for combat.”

Slovik and Private John Tankey, the friend with whom he sought cover during the bombardment, wandered around for a while. Eventually they encountered a Canadian military police unit. They spent the next six weeks with the Canadians, after which they finally joined their designated unit.

Slovik became persistent in his attempts to avoid combat in any way possible. When he was refused transfer in a rear unit, he became determined to desert. On October 9, that was exactly what he did. In order to make his intentions clear, he wrote a letter which he handed to an enlisted cook at his headquarters detachment, who was to serve as his messenger:

I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion, we were in Albuff in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my foxhole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed overnight at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE.

— Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415

He was soon captured and taken into custody. Slovik was then brought before Lieutenant Colonel Ross Henbest, who offered him the chance to return to his unit and forget about deserting. The cook and the military policeman whom he had met before his capture both advised him to do so as well, before it was too late.

What constitutes as bravery, in this case, was the fact that Slovik refused to stand down from his decision, no matter the price. On the other hand, he was also aware that, given the circumstances, the worst thing that could happen to him was a dishonorable discharge and a prison sentence, all of which he considered far more acceptable than combat.

After he refused all of his chances to return to his unit, Slovik was court-martialed. His trial could not have occurred at a worst time. In November 1944 the Battle of Hurtgen Forrest, which proved to be the longest and perhaps the bloodiest battle that the US Army faced during WWII, was entering its third month.

The fear of desertion was becoming a real threat to the American war effort, as the winter weather was taking its toll on an otherwise successful campaign in continental Europe. Slovik was court-martialed and sentenced to death, partially as an example to others who thought desertion was an option.

Once he realized he was actually going to be executed, Slovik wrote a plea addressed to General Eisenhower. His desperate last attempt to preserve his life was rejected and on January 31, 1945, just a few months before the war ended in Europe, Edward Donald Slovik was executed by firing squad.

As noted earlier in this article, a number of other soldiers were sentenced to death for desertion, but their sentences were all revoked due to different reasons. The US Army certainly did not feel comfortable with killing their own men. But Slovik’s case was different. The way he acted, his nonchalance towards authority and the fact that he had even written a stubborn explanation for his decision apparently triggered his superiors much more than he expected.

Slovik was buried in the notorious Plot E of Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial in Fère-en-Tardenois, alongside 95 other members of the US Army; all of whom were sentenced to death due to crimes such as rape and murder.

This decision sparked sympathy after the war, as Slovik’s honest statement was perceived as an act of a true pacifist by some and not that of a coward. Somewhere in between, Slovik’s soul still roams. Before we cast the stone of judgment concerning his fate, we must first realize how absolutely horrendous it is to witness the devastation of war. Slovik’s rational fear overcame his sense of duty which was not at all uncommon during the time. However, the combination of circumstances made him the only one who had to pay for his decision with what he considered dearest ― his own life.