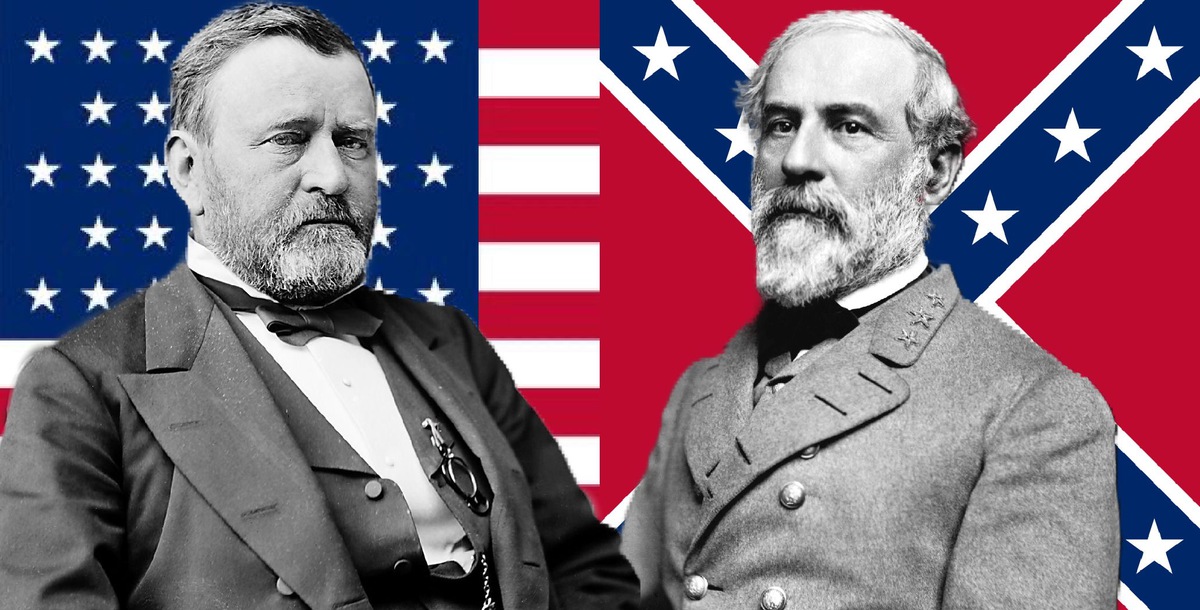

It is the American Civil War. You have been walking hundreds – perhaps thousands of miles – in tattered clothes and worn out shoes. You have survived mosquito-ridden forests, ferocious battles, and fires, starvation and misery and now your regiment’s route is taking you within ten miles of your home. Would you desert, or keep on marching to your probable death?

What is desertion?

The act of desertion should not be confused with either cowardice or a rout. If a soldier did indeed slip away and go home, that would be desertion. Desertion is the act of leaving the military with no intent to return. A soldier on his own abandoning a battle would be charged with cowardice. If several soldiers run from battle all at once, then it is a rout.

These three things are treated differently in consequence and punishment. The penalty for cowardice being the harshest, both officially and as a blight on a man’s reputation for the rest of his life; if he was not sentenced to death.

Who were the deserters?

These men were not usually cowards. It was not about their own safety; desertion was generally for practical reasons or principles. A lot of deserters had been in the war for a long time and had been through several horrific battles.

The official numbers for each side are 103,400 Confederate deserters and 200,000+ Union.

Most deserters on either side came from hilly, rural regions: New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, North Carolina, and Virginia.

Why did soldiers desert?

Proximity:

When a soldier’s unit was skirting around the area he was from, he had an opportunity to escape and care for his family. It was easier for men that lived in backwoods places with plenty of hills, caves, and woods to hide in should anyone decide to chase after him.

Hardships at Home:

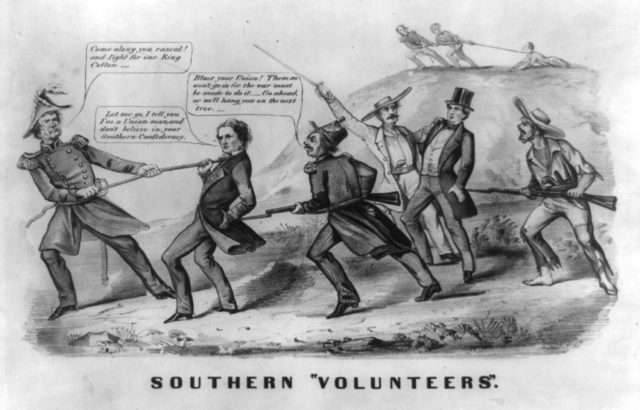

Both sides thought the war was going to be over in a heartbeat. Those that had volunteered never intended to be gone for long and there was little preparation for the families they left behind. Those that were drafted or were forcefully taken through conscription by local militias enforcing the draft had even less time.

The women, children, and men not able to go to war were faced with financial ruin. They were losing their homes to raids and fires or were unable to deal with agricultural demands or earn money. Many were near starving.

Incentive:

The US government bribed Confederates to desert by offering them amnesty, restored citizenship, and pardon if they swore loyalty to the Union. They also offered them money late in the war.

Because they could:

Southern deserters were mostly from mountainous areas. Those from the lowlands had a harder time. Slave labor was keeping farms going, and politicians and citizens in those areas were mainly in support of the war. Any deserter trying to come home to one of those areas would do so at risk of harm or death.

Some men never got close enough to their homelands to desert. The trek home would have been far too long and perilous. Most who did desert were those that could.

Principles:

Both armies were full of soldiers who had signed up to a contract that was being ignored or forgotten. They thought the government should live up to its promises and when it did not, they felt free to leave. Southerners believed the Confederacy was caring for their loved ones and Union soldiers wondered why their service kept being extended.

Intolerable Exposure and Disease:

More soldiers were dying from diseases than from warfare. Terrible epidemics such as smallpox, dysentery, malaria, and typhoid swept through their camps. They were plagued by lice, mosquitos, and other insects leading to a maddening condition called the Army Itch.

Camping is fun for a day or two. They had been trudging and sleeping for months and years in the wet and cold and hot and humid and would have been very demoralized. These soldiers saw men dying all around them. They could not go home on leave. There was no break. It was interminable hell.

Fraud:

“Bounty jumpers” were Union men that took advantage of the system. To recruit more soldiers, the Union paid “bounties” of $300 to each man who enlisted. Three hundred dollars is equal to $5968 now. A soldier’s monthly salary was $13 a month, so $300 was almost double what he would have earned in a year.

In an age before photo identification, some people took the money and then left. They went to another place, joined under an assumed name and collected another bounty.

The Confederate bounty system paid too little (and the money became worthless) for this scam to be worthwhile in the South.

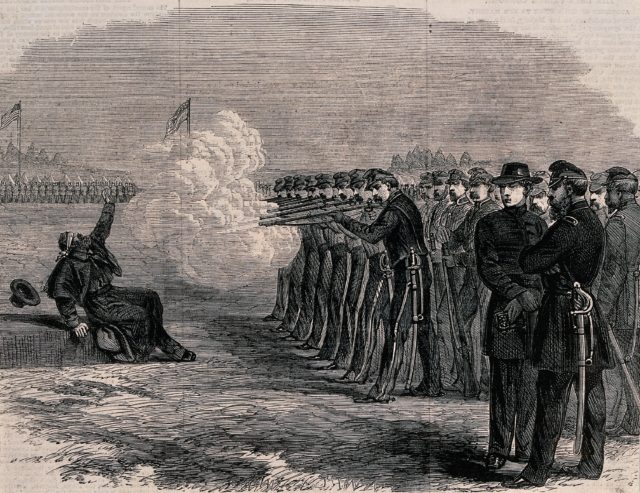

What were the consequences?

The laws were loose and confusing. Neither side had formal laws concerning desertion at the outset of the war. Officers took it upon themselves to come up with makeshift rules.

In 1863, the Union finally wrote out a formal policy. The Confederacy did the same with an act that made aiding deserters a criminal offense. The Confederate’s General Lee confused the laws yet again in 1864 by offering amnesty to Union deserters.

President Lincoln felt that desertion laws were harsh and pardoned many condemned soldiers. He also mandated that no soldier under 18 years of age could be executed.

Of the many deserters, very few were executed. Those that were died as “examples” of what would happen. For the most part, armies threatened execution but pardoned men if they returned to their ranks. The worst punishments were meted out upon bounty jumpers who were tortured with thumbscrews, sentenced to war prisons like Andersonville, or executed.

War pensions were also structured so that a soldier had to have an honorable discharge to receive one. After the war, some deserters were able to get that pension when their records were “corrected” by acts of Congress to amend the military record in their favor.