He didn’t dream of being a soldier or a flying ace and was happy with his desk job.

Oskar Gröning was 94 years old when he had to stand trial for war crimes from WWII.

He maintained that he had been only a “small cog” in the Auschwitz machine, but he was still sentenced to four years in prison.

The court case made headlines around the world. It sparked such interest that Signature Entertainment made a documentary about Gröning, his life, and his trial.

The 75-minute documentary will be available on DVD and Digital HD from April 15, 2019.

Gröning’s childhood

Gröning’s early life certainly influenced his later crimes.

His mother died when he was just four years old. He was brought up by his father who was a nationalist and strictly conservative. Gröning described his upbringing as one filled with “discipline, obedience, and authority.”

His father had fought in the First World War and felt strongly that Germany had been treated badly in the Treaty of Versaille.

Military service ran in Gröning’s family. He claimed that one of his earliest memories was looking at pictures of his grandfather who had served in an elite regiment of the Duchy of Brunswick.

He had been part of the Scharnhorst in the 1930s and later joined the Hitler Youth where, among other things, he burnt Jewish books.

He claimed he only wanted to free Germany from the culture of others. He felt that National Socialism would benefit the German people and the economy.

The accountant goes to Auschwitz

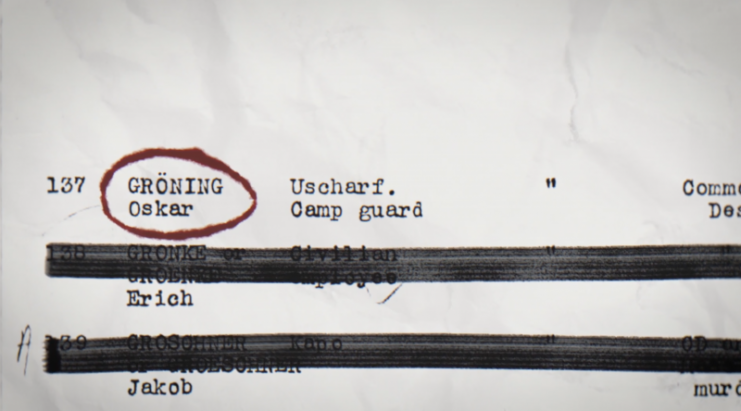

Gröning became a trainee bank clerk when he was 17 years old. When war was declared, eight of the twenty clerks were conscripted. However, Gröning and several of those left behind didn’t want to advance their careers – they wanted to do their bit for Germany as well.

Inspired by Germany’s swift victories in France and Poland, Gröning joined the Schutzstaffel. He didn’t dream of being a soldier or a flying ace and was happy with his desk job that combined career and military opportunities.

In 1942, the SS declared that desk jobs should be reserved for injured veterans. Gröning and 22 of his colleagues who were to be reassigned were sent to a briefing in Berlin.

There, they were told they were going to be assigned to a task so secret that they had to sign declarations promising not to talk about it with friends, family, or anyone outside their unit.

Gröning and the men were then sent to a place they’d never heard of before: Auschwitz. When they arrived, they were warmly greeted by SS officers. Gröning was surprised to be given a meal that was much better than the standard SS rations.

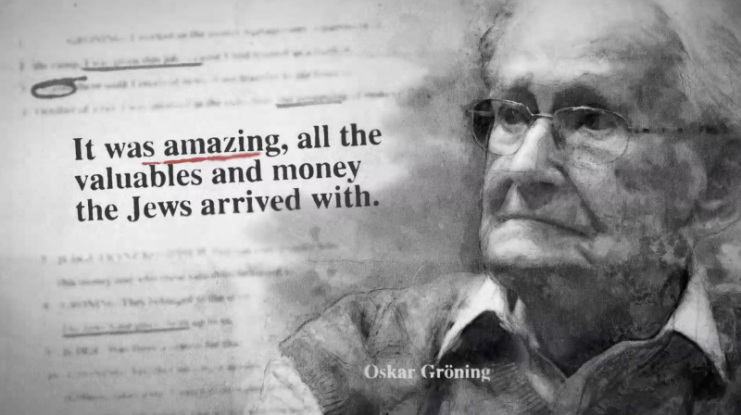

Due to Gröning’s bank skills, he was sent to the barracks which housed the prisoners’ money. He was informed that when the prisoners arrived, their money was taken away and stored, to be returned to them when they left.

At first, Gröning believed what he’d been told. However, it was clear that Auschwitz was a different kind of concentration camp and he eventually learned that the money he was counting was not returned to the prisoners because they never left the camp alive.

Even on his first day, Gröning witnessed people being shot. But it wasn’t until he saw a soldier killing an abandoned baby by smashing its head against the wall that he told his superiors that he couldn’t work there anymore.

Gröning felt that if Jews needed to be exterminated, “then at least it should be done within a certain framework.” But his superiors forced him to continue working, using the document he had previously signed against him.

Due to the administrative nature of Gröning’s work, he was often shielded from the greatest horrors of the camp. However, after another incident where he witnessed some escaped prisoners being gassed in a farmhouse, he took even greater care to ensure that his life at Auschwitz avoided the worst of the butchery.

Life after Auschwitz

Eventually, Gröning managed to secure a transfer to a front-line unit in 1944. His unit surrendered to the British after Germany capitulated in May 1945. In a darkly ironic twist, they were imprisoned in an old Nazi concentration camp.

Gröning realized that revealing that he’d spent time in Auschwitz might result in a “negative response” from his captors. So, instead, he claimed that he’d been a clerk at SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt (a Nazi organization responsible for finances and other administrative matters for a paramilitary organization).

In Lawrence Rees’ book, Auschwitz: The Nazis and ‘the Final Solution,’ Gröning is reported as saying that he told this lie because “the victor is always right” and that some of the goings-on at Auschwitz “did not always comply with human rights.”

In 1946, he was sent to the UK as a forced laborer and enjoyed a quite comfortable life. He ate well, earned money, and traveled through Britain performing in concerts where he sang traditional German hymns and English folk songs.

Back to Germany

Gröning was able to return to Germany sometime around 1947-8. He reunited with his wife and lived with his father-in-law.

He refused to talk about his experiences during the war. At the dinner table one night, an off-hand remark was made implying that he might be a real or potential murderer. He flew into a rage and demanded that the subject was never raised again. It wasn’t.

He was unable to get a job at the bank, so he worked at a glass factory where he rose to a managerial position.

After the war, he made some comments in response to some Holocaust denial literature. He wrote to Thies Christopherson, a prominent Holocaust denier, and said: “One and a half million Jews were murdered in Auschwitz. I was there.”

His words were published in a Neo-Nazi magazine, and he ended up receiving phone calls and letters from people arguing with him. He described how people “tried to prove that what I had seen with my own eyes, what I had experienced in Auschwitz was a big, big mistake.”

As a result, Gröning decided to speak publicly about his experience. He asked forgiveness from God and the Jewish people, but always maintained he was merely a “small cog” in the great machine of extermination.

The Trial

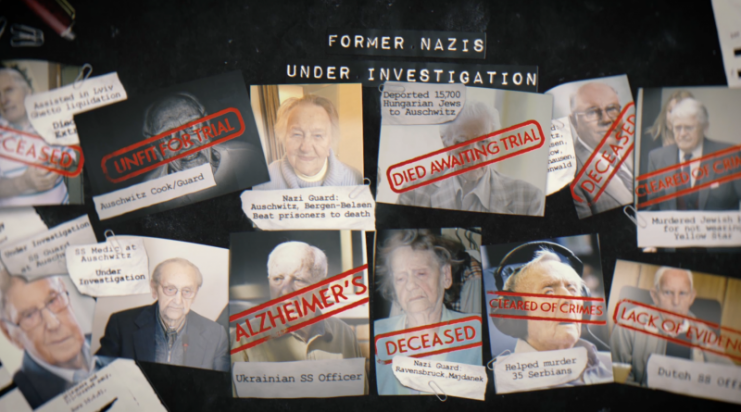

In September 2014, charges were brought against Gröning by state prosecutors as a last great push by Germany to bring those charged of Nazi war-crimes to justice.

According to the German newspaper, Zeit, for legal reasons the indictment against Gröning was limited to the so-called “Hungarian action” which took place in the summer of 1944. But even limiting the charges in this way meant that Gröning was on trial for the deaths of 300,000 people out of 425,000 who arrived in 137 rail transports during that time.

The trial began on April 20, 2015. In the following days, the court heard from 60 co-claimants. Under German law, a victim or certain offenses or a spouse, life-partner, child, sibling, or parent of a homicide victim can act as a “co-claimant.” This is in addition to the state prosecutor who is the principal claimant in a trial of this kind.

Ultimately, he was convicted of being an accessory to the murder of about 300,000 people and sentenced to serve four years in prison.

Public response

Public reaction to this trial has been mixed.

Some people feel that it’s important to bring these crimes into the light and ensure that the perpetrators are punished. Others just want to move on and leave that terrible past where it belongs – in the past. But there’s a worry that if we don’t learn from our mistakes, we’re doomed to repeat them.

However, Eva Moses Kor, an Auschwitz survivor and co-claimant at Gröning’s trial, had a different view. In July 2015, she was reported as saying: “They are trying to teach a lesson that if you commit such a crime, you will be punished. But I do not think the court has acted properly in sentencing [Gröning] to four years in jail. It is too late for that kind of sentence… My preference would have been to sentence him to community service by speaking out against neo-Nazis. I would like the court to prove to me, a survivor, how four years in jail will benefit anybody.”

Gröning’s appeal was denied and, in August 2017, he was declared fit for jail. The Federal Constitutional Court ruled that his advanced age was not a reason to avoid prison time.

However, on March 9, 2018, Gröning died in hospital before he could begin his sentence.

The Documentary

The documentary about Oskar Gröning’s life is written by Ricki Gurwitz, directed by Matthew Shoychet, and will appeal to those who enjoyed the popular series Making a Murderer.

It premiered in 2018 and will be available to own on DVD and Digital HD on April 15, 2019.

It is important to remember the past, to learn from it, and to avoid repeating the same mistakes. This documentary, covering the trial of a man who was shown to be an accessory to the death of 300,000 people, is a reminder of what atrocities have been committed in the past.

Gröning’s case shows us that being a “small cog” in a deadly machine doesn’t mean you can avoid responsibility for the deaths that occur.