Most military commanders will think twice about an attack unless they have an advantage in numbers over the enemy.

However, in 1532 a Spanish conquistador found himself facing an Inca army which outnumbered his tiny force of mercenaries by more than five hundred to one. Undaunted by these overwhelming odds, he decided to attack.

Francisco Pizarro was a Spanish adventurer who came to South America in search of gold. He was a soldier who had spent time fighting in Italy where he gained a reputation for courage in battle.

He first arrived in present-day Columbia in 1502, ten years after the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus. For almost 30 years, Pizarro led expeditions in various parts of South America in search of riches which he conspicuously failed to find.

However, he heard persistent rumors of a people who lived in the Andes Mountains in present-day Peru who were said to possess fabulous quantities of gold.

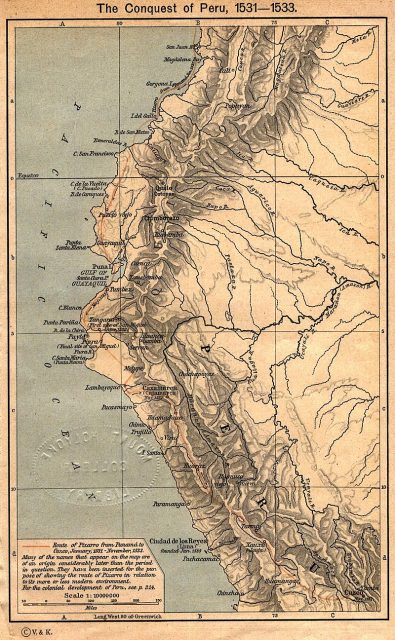

In 1531, he was finally given license to explore the Andes Mountains on behalf of the King of Spain, on the understanding that one-fifth of any treasure he found would belong to the Crown.

He had sufficient money to hire just one ship and a small band of mercenaries. Many of these men were, like Pizarro, grizzled veterans of conflicts in Europe and South America.

Pizarro was 55 when he set off on this voyage, and some people considered him to be too old to be an effective commander. The average life expectancy in Europe at that time was less than 40, and it was relatively rare for a person to reach Pizarro’s age.

Though he didn’t know it when he landed on the coast of Peru, Pizarro was about to take on the most powerful empire in South America.

By the early 1500s, the Inca Empire stretched for more than 1,000 miles from north to south and incorporated more than fourteen million people.

Inca armies were huge – on some occasions, up to 200,000 men had taken to the field under the command of the Sapa Inca, the supreme ruler.

However, the Incas had recently been involved in a bitter and protracted civil war when two brothers, Huáscar and Atahualpa, fought to become the new Inca leader.

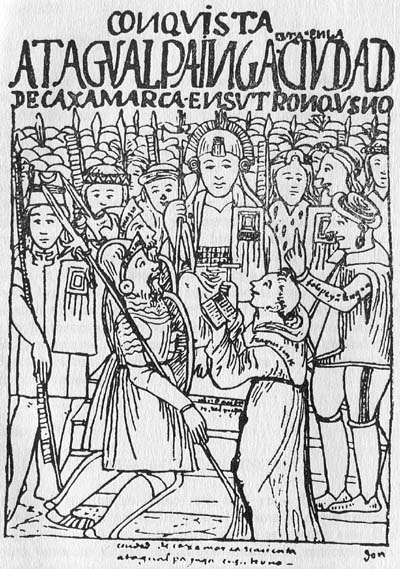

In early 1532, Atahualpa finally defeated his brother and established himself as the new Sapa Inca.

The Incas had heard of the Spanish explorers with their strange customs and clothing, and Atahualpa was curious – he wanted to see these odd people.

When he learned that a small group of them had landed on the coast of Inca lands, he sent an envoy to guide them to the city of Cajamarca in the highlands of northern Peru, 9,000 feet (2,743 meters) above sea level.

The Sapa Inca did not feel in the least threatened by these foreigners – Pizarro’s force numbered just 168 men, including four of his brothers.

They were completely isolated, deep in Inca territory and Atahualpa waited for them with his army of 80,000 men, battle-hardened and recently victorious in the civil war.

Pizarro and his men arrived in the city on November 15, 1532. Most of the civilian population of Cajamarca had been removed on the orders of Atahualpa, and Pizarro quickly realized that his situation was precarious.

The Inca army was encamped on the heights above the town and it was clear that it massively outnumbered the Spanish force.

Retreat was not an option as the route back to the sea would take the Spanish close to several large and potentially hostile Inca fortresses. Pizarro explained to his apprehensive men that the only viable plan was a bold attack on the Incas.

Atahualpa arrived in the city with around 7,000 of his men during the evening. The remainder of his army was camped in a meadow just outside the city walls.

There was a meeting between Pizarro and the Sapa Inca, though this led to confusion due to a lack of reliable translation. It was agreed that the Incas would return the following day.

In preparation, Pizarro’s soldiers concealed themselves in buildings surrounding the main square.

The Spanish mercenaries were equipped with the latest and best in European weapon technology: spears and swords made in Toledo (said to be the best in the world), crossbows, a small number of arquebus muskets, and a few small cannon.

Most of the Spanish soldiers wore armor also made in Toledo which included a heavy breastplate, arm and leg greaves, neck protection, a metal skirt which protected the groin, and a helmet called a morion.

The Inca warriors facing them had no armor and most carried only heavy clubs, axes, or maces. These were useful in combat with other South American armies, but they were almost completely ineffective in combat with the armored conquistadores.

Inca weapons could bruise and batter the Spanish soldiers, but they could not or kill or incapacitate them.

When Atahualpa returned to the city with around 7,000 followers the following morning, Pizarro ordered his concealed troops to attack.

What followed wasn’t really a battle. It barely even qualified as a rout. It was simply a massacre.

No-one is entirely sure how many Incas died that day, but the total was certainly several thousand. Spanish casualties were zero.

Atahualpa was taken prisoner and when the 70,000 remaining soldiers of his army outside the walls heard about his capture and the massacre of their comrades, they fled without a fight.

Seldom in the history of warfare has such a tiny force achieved such a total victory over an enemy of vastly superior numbers.

With the benefit of hindsight, the reasons are clear. The Spanish force included a few cavalry, which the Incas had not seen in action before, and a charge completely un-nerved them.

Firearms were also a factor – the Incas had never faced these before either.

However, the main factor seems to have been a realization on the part of the Incas that in hand-to-hand combat their weapons were unable to harm the heavily armored Spanish soldiers.

Tactics were an issue too. The warfare that the Incas were used to was heavily formalized and ritualized. Things like ambush and subterfuge were completely unknown to them.

They were also heavily dependent on the direction of officers and nobles, and when large numbers of these were killed in the initial ambush, the remainder of the army rapidly disintegrated.

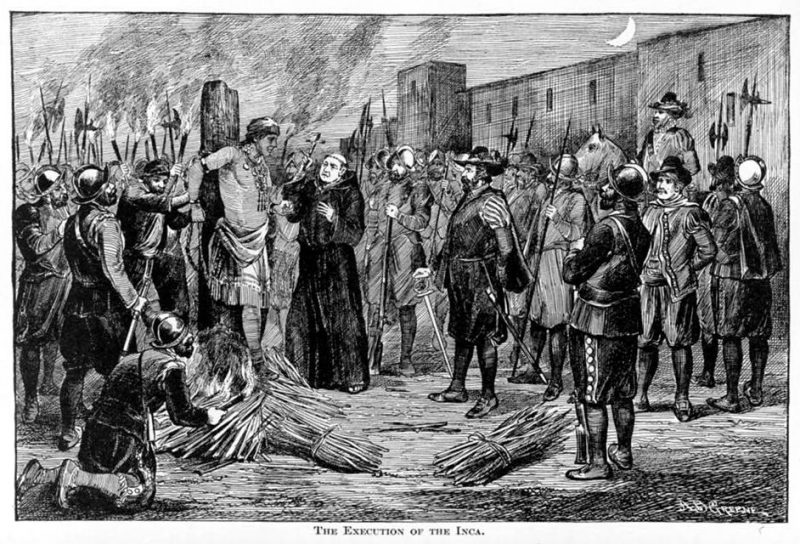

Pizarro kept Atahualpa as a hostage and demanded that the Incas fill a large room with gold as ransom. It took eight months, but the Incas were finally able to do this, using relays of carriers to bring gold from every corner of the empire.

When the room was filled to Pizarro’s satisfaction, he had Atahualpa executed anyway and used the ransom to fund a larger mercenary army with which he conquered the Inca capital, Cuzco, one year later, signaling the effective end of the Inca Empire.

Pizarro was assassinated in 1541 following a squabble over the division of the spoils of his victory. The last leader of the rump Inca state was executed in 1571.

There were many other battles between the conquistadores and the indigenous people of South America in the years to come, but none were as one-sided or decisive as the Battle of Cajamarca.