War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from the esseist Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi.

After more than 70 years, the Italian son and the Australian daughter of two NCOs on enemy ships meet and recall, through their parents’ diaries, the fate of the naval battle off Crete on July 19, 1940.

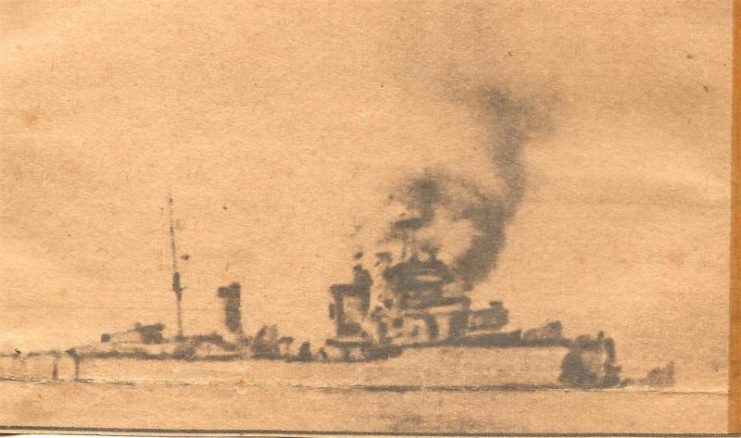

The Australian cruiser Sydney, in command of a squadron of five English ships, sinks the Italian light cruiser, Bartolomeo Colleoni.

The Battle

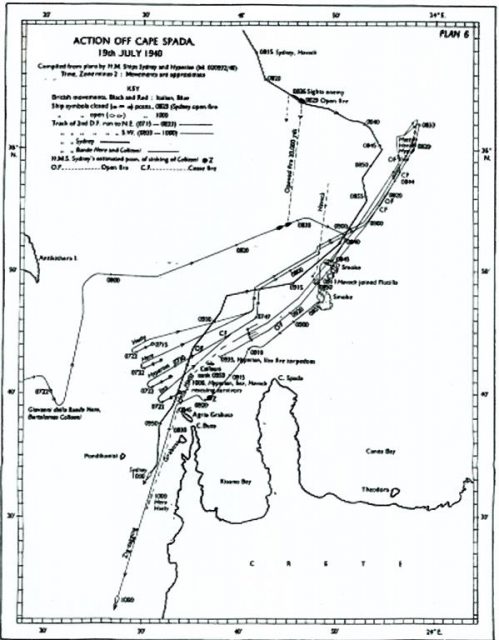

At dawn, on July 19, four British destroyers, Hyperion, Ilex, Hero and Hasty, were sighted by Giovanni delle Bande Nere and Bartolomeo Colleoni, 16th-century captain of fortune class light cruisers, sailing from Tripoli to Leros. The order to attack was given. The speed was increased and the engagement with the naval guns began shortly thereafter.

The English ships reversed the route followed at maximum speed by the Italians until, on the left side, the outline of an enemy cruiser, the Sydney, followed by a second one, the Havock, suddenly appeared and came into action.

The Colleoni was hit in its vital point: the electric power generator. It stopped.

The Bande Nere emitted a smokescreen and circumnavigated the immobilized sister ship waiting for the damage to be repaired.

The Sydney was getting closer and closer and the Bande Nere was forced to move away so as not to be hit in turn, whilst the Colleoni was easy prey of the enemy although its manually operated main armament continued to shoot.

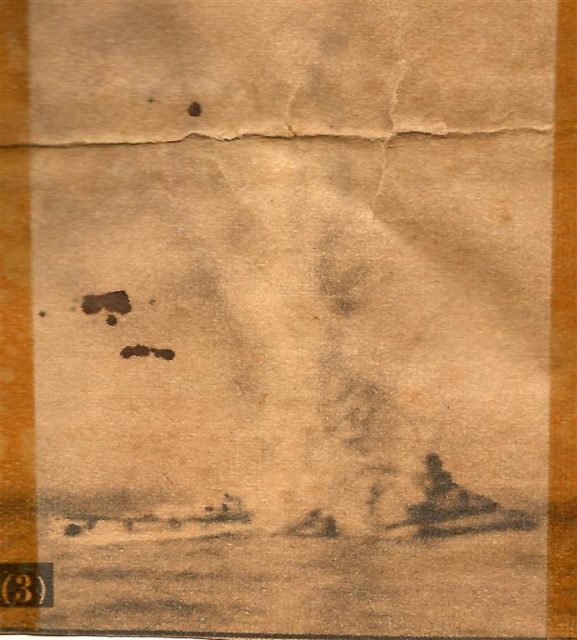

Sydney, Hero and Hasty tried to reach the Bande Nere meantime Havock, Ilex and Hyperion were launching torpedoes that struck the bow of the Colleoni, cutting off a hundred feet of hull. Then its centreline was slashed giving way for water to flood into the ship. Colleoni rolled over and, lifting the stern slightly, sank rapidly.

The lifeboats for the recovery of the shipwrecked sailors departed from the British units. The operation lasted a few hours until the arrival of Italian torpedoe aircraft flying from Rhodes. Many sailors were abandoned at sea and lost their lives. Those who tried to reach the coast found themselves in front of only steep rock with no holds. More than 500 men were rescued and 121 died.

Responsibilities

The two Italian ships of the Condottieri class, fast and manoeuvrable, were vulnerable due to the reduced armour of the hull to the blows of 6”guns. The outcome of the battle, in addition to the lucky blow that stopped the Colleoni’s life, is due to several factors; we mention some. Lack of aerial reconnaissance. The arrogance of the Dodecanese Governor, De Vecchi, delayed the departure of his “own” military Italian aircraft. This caused the ships to fall into the trap but allowed the rescue of half of the Colleoni’s crew. The arrival of the planes, after hours of delay, forced the English ships to abandon the rescue area. De Vecchi was thrown out from his position after a few months.

In this regard in para196 of the R.A.N. Ships overseas June-December 1940 ” is reported … In one particular example, the action provided a lesson for the British. The delay imposed upon the Hyperion, Ilex and Havock by their stopping to rescue Colleoni’s survivors may have contributed to the escape of Bande Nere was an experience which brought home the unpalatable fact that British commanding officers could not afford to permit the escape of enemy vessels. They must harden their hearts in similar circumstances in the future. An order to this effect was issued.

Piero Baroni, in the book “Una Patria venduta (A sold country)” writes: “What is called a sudden encounter was actually a real enemy ambush implemented on the basis of precise information from an unfaithful Italian source.” This statement is motivated in the book ” Gli eroi vinti – The heroes won”: – why were the two cruisers sent to sea without the necessary escort? – Why was the plane not catapulted for reconnaissance? It represented a danger to the ship during the combat with its fuel load and its position above the stern turret that did not allow the full tilt of the guns. The explanation was that there was very rough sea while on the English side calm weather conditions were reported. – Why did not the two cruisers continue the route to Leros? – Why did not Admiral Casardi break the radio silence at the start of the fight and wait an hour and a half before asking for air intervention? – Why did the Bande Nere, under the command of captain Maugeri, manage to get out and save himself? The answer is in the citation of decoration awarded by the Americans. It reads: “For the exceptionally meritorious conduct in the execution of very high services rendered to the United States government as head of Italian naval espionage.” Perhaps one day, History will clarify all doubts.

Italian View Point

Operation Order

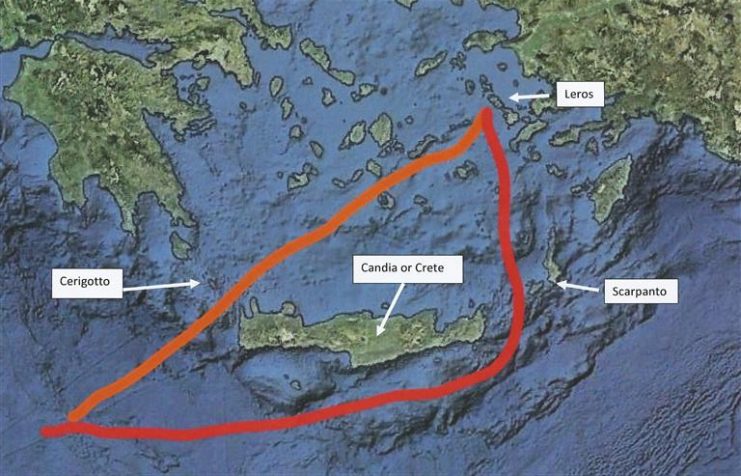

For a short time, the Bande Nere and Colleoni cruisers will soon be displaced in Portolago (Lakki – Leros island), under the command of the Division Admiral Ferdinando Casardi. The purpose of the temporary relocation will be to perform raids in the waters of the Aegean to cause maximum damage to the enemy traffic if it turns out that the British were concentrating vessels in Crete coming from the Turkish or Greek ports. […] The Division will arrive in Portolago in the early afternoon of a day that I will communicate only at very short notice, after performing at Sollum (Cyrenaica – Libya) a sudden heavy bombardment. A route will follow passing through the channel between Rhodes and Scarpanto, or between Heraklion (Crete) and Cerigo.

The Chief of Staff F.to Cavagnari.

On July 17 at 09.30, Supermarina orders the Second Navy Division to prepare for departure and transmits to Admiral Casardi the message: “SEDICI TRASMISSIONI ERRATE”. This meant that the departure was to be understood on the 17th with destination Leros without carrying out the planned bombardment of Sollum.

A subsequent message was sent:

21.00 hours on July 17th departure from Tripoli. Transit 30 miles north of Derna at a speed of 20 knots; passage between Cerigotto (Andikithira) and Crete. Guaranteed aerial reconnaissance insurance from Egeomil.

Arrival in Portolago (Lakki) 19 July at 14.30

In navigation

A sailor writes:

18 July 1940. The night runs down quietly. In front of us the “Bande Nere” black silhouette slits the horizon line. The deep silence is broken by the waves lapping against the bow and then sliding on the hull to be swallowed by the sea.

The hours are slow, marked by the changing of the guards. An exchange of orders, some excited greetings , agreements for the next franchise in Rhodes, a hurry of steps and then a vigilant silence: silence of war.

It is dawn of 19 July and the ship awakens with the usual noises, there at the end, the horizon line is covered by a thick haze. Another day awaits us but, suddenly, a trumpet blast tears the air, followed by a sharp command “Combat post”. In a moment we are at our posts: watchful, with the nerves on edge, ready to respond to the commands.

Two enemy ships run on the horizon, our batteries open their din of death. Our ship runs safely on the waves, but from a distance comes a deafening roar like thousand trains clatter on our heads. Death responds to death, orders are the same on the fronts: “Fuoco – Fire”. The roar is followed by harbingers of destruction but from our mouths comes out a cry of rage. The ship slowly stopped, its torn heart ceased beating; death begins to play his macabre dance in the green meadow of our youth […]

From the bridge, the commander Novaro, despite being seriously wounded, strives for the safety of the crew and launches his hoarse cry of pain “save those who can”, while with flying colours accompanied the sinking ship. He was determined to stay in his place, but some officers forcibly put a life buoy on him and pushed him into the sea. […] Meanwhile, the ship as a living creature, rolls on its side and slowly slides into the abyss.

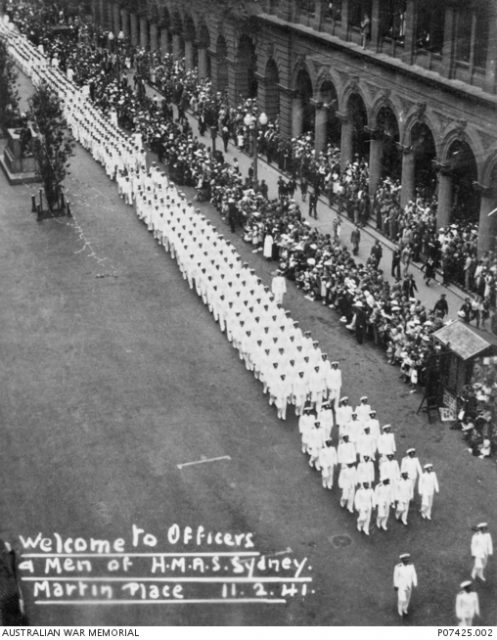

Alexandria in Egypt

In the port of Alexandria in Egypt all the Mediterranean Fleet ships celebrated the victorious return of the squadron after the battle of Cape Spada. The sailors were waving on decks to greet the winners, throwing up into the air their hats. It was a riot of flags and sirens that gave a warm welcome back to fellow sailors.

The Italian prisoners were put ashore and located in a square awaiting further orders.

Who would have thought of arriving here under these conditions. Naked, dirty, tired.» Said Gastone Tanzi, war correspondent on board the Colleoni, addressing a young non-commissioned officer who was at his side. «Perhaps we are half as many as we were leaving from Tobruk. Unfortunately they beat us and we must accept it. Feel how they greet the arrival of the ships ! The port is at the party. They had a nice day of hunting. If Admiral Casardi had been more versatile he would have launched the reconnaissance plane and would have discovered the ambush we were running into. It seems that he did not use it because there was a lot of wind and it would have been difficult to recover it afterwards. Among other things, he was sure of the air surveillance intervention from Rhodes.

The blast of a whistle, repeated several times, was heard and the prisoners were directed towards the exit of the port where about twenty trucks were lined up. Two long queues of onlookers had formed along the road watching the prisoners passing by; it was the first time that it happened in town. The Italians, dressed like beggars, were truly mortified. Someone, on board, had received clothing from the British so that they would not remain naked.

Look at those old women. They raise their dresses to show their nudity. What a disgust!: said a sailor. Look those beggars how they laugh. Those s**ts spit on us: Said another one. Let’s go! Pretend nothing: replayed someone.

The ambulances shuttled to the British military hospital for the hospitalization of the wounded while the truck column transported the prisoners to the opposite end of the port, to Mostafà (el Nahaas), suburb where they were left in a building guarded outside by armed English sailors.

From the opposite side

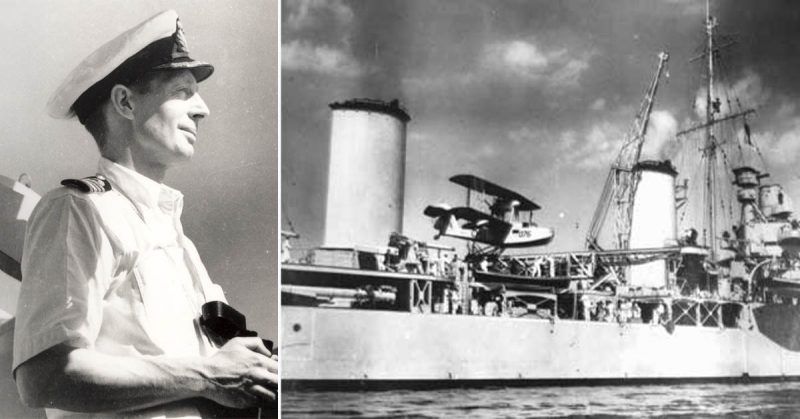

Extract of Petty Officer’s diary, Charles Nelson, HMAS Sydney Cruiser Turret “A” Chief Gunner

July 18, 1940, at 4 in the morning. I was aboard the Sydney under the command of Captain J.A. Collins and we set sail with the destroyer Havock from Alexandria in Egypt. We were ordered to support the destroyer flotilla Hyperion, Ilex, Hero and Hasty engaged in the hunt for enemy submarines in the waters off Crete and destroy the enemy ship direct or coming from the Dodecanese. It was known that an opposing ship was sailing in that area. The flotilla took the sea just before us.

We had spent a day without worries, just like cruising in the Mediterranean. At 21.30 we were sailing along the Dodecanese. It was the most dangerous point for aircraft attacks based at the airports of those islands. Nothing happened. The ships were zig-zagging to protect themselves from submarine attacks. The night passed quietly.

In the morning, I had just gone to breakfast, the message announcing the sighting of two enemy ships came from the Hyperion. It was 08.00 of 19 July. The mutual discovery of ships could have happened even earlier if the cruisers had used the seaplanes supplied for reconnaissance. Sydney found it impossible to do so because its plane, hit in the Bardia action, had not been replaced; on the Italian side a prisoner reported that at about 06.00 that morning there was an attempt to catapult a seaplane but the operation failed due to its malfunction.

At 08.27 the two enemy cruisers passed from the line formation to the side-by-side in order to use all the weapons on board; they opened fire with 6″ guns at a distance of 17,400 metres on two of our destroyers closest to them. Instead of accepting the duel, our ships reversed the course heading for the Gulf of Athens to approach us.

In this first phase of the fight the Italian cruisers had the possibility to shoot keeping out of reach of the guns of our ships. These, in fact, answered the fire but the shots were short; they also launched torpedoes that did not reach the target because they were at a greater distance than their range, around 18,000 metres.

Also from the Italian side the shot had little effectiveness; with the dazzling sun in front, the sighting operations were difficult. Meanwhile the distances were increased because our destroyers were faster, about 35 knots; the Italian ships sailed at 32 knots, almost at their best.

Suddenly the Italian ships stopped shooting. Suddenly they changed course while our destroyers emitted a curtain of artificial fog that, added to the morning mist, made them totally invisible. The flight of our ships should have generated some suspicion; their rapid retreat had to make clear that they were trying to lead the opponent under the firing of other units not in sight at the time.

The Hyperion Commander, Nicholson, continued to transmit messages on the presence of the two Italian ships signaling their position, course and speed which allowed Collins to know where to go. He kept absolute radio silence to guarantee surprise with his intervention even if, in doing so, he did not reassure Nicholson, nor the admiral Cunningham in Alexandria who urged Collins to intervene. Our commander did not want to reveal his presence. Among other things, contrary to the orders received at the start, he thought he did not want to go deeply into the Gulf of Athens because he feared that in case of an attack it would be difficult for him to maneuver. It was a wise choice because it quickly reached the flotilla. The order: Close Up To Action Stations was issued when the bow was directed to intercept the Italian cruisers.

At 08.20 we sighted the two cruisers to starboard at a distance of about 23,000 yards with the EEN route. They did not suspect us. They were armed with 6” guns and not 8” as we supposed. We opened fire with the main armament having mastered the surprise, the Italians responded to the fire. The sudden appearance of Sydney and Havock was a surprise even for the friends and from that moment they kept in touch with the radio. The two groups joined North of Cape Spada. The target range on the Bande Nere was well centered and she was hit.

The Bande Nere and the Colleoni were in difficulty due to the lack of precision in their shooting because of an ineffective telemetry system; their shot seemed to be adjusted to the flashes that appeared in the haze. They approached 90 degrees on the starboard, continuing the shot with the stern turrets. A shell fell on our bow stack; the damage was not serious and only a sailor was lightly wounded. Even our shot became inaccurate because the adversaries concealed themselves with a misting curtain but, after a few minutes the units, ceased to fog and pulled straight to the right heading south.

The Sydney, the Havock and the four Flotilla destroyers were all in pursuit of Italian ships. Italian cruisers were faster than Sydney and were gradually moving away at a speed of 30 knots.

At 09.02, Sydney opened fire again against the Bande Nere at a distance of 21,000 yards and continued firing until 09.08. The situation seemed favourable to the opponents because they could count on 16 pieces from 6”against the 8 of Sydney and the 20 pieces from 4.7”of the five destroyers who had not represented a serious danger until then for their limited range. The Italians tried to get into open water and stay in position to be able to launch the torpedo more conveniently, but they did not.

At 09.24 continuing shooting with all the turrets and making frequent route changing to disorient us, the opponents were almost at the cross of Cape Kimaros, 5 miles beyond Cape Spada. The Colleoni, framed by our precise shot, was hit by the first shot. The ship lost speed then it was no longer governable but continued to proceed until it stopped altogether. In the following minutes the Colleoni was hit in all the other areas of the hull, particularly in the centre and on the tower, with serious losses among the personnel, damage to the structures and fire outbreaks.

The Bande Nere emitted smoke to make Colleoni less visible as he turned around. It was not enough. The Sydney’s shots were joined by those of the approaching destroyers. The shells hit the boiler room because a dense cloud of steam was seen. Shortly thereafter electric power was also lost on that ship because everything became still. The Colleoni continued to shoot with the 4” guns manually operated against our ships approaching fast. Our vessels fired on the easy target and under the hail of blows the tower and the bridge were destroyed and burned. The Colleoni was now a smoking wreck. From a short distance, Ilex and Havock launched torpedoes that first hit the easy target at its bow, causing the detachment and the immediate sinking of about thirty metres of hull, and then in the middle of the ship a large opening allowing the sea to rush in. It turned upside down and sank rapidly lifting the stern a little.

The dozens of shell holes in the hull and upperdeck other than in the funnel indicated great devastation to the interior of the ship. Clouds of steam and black smoke escaped from the cavity of the funnel because of the fire in the engine department and in the boilers. The metal part above the bridge was all curled up, pieces of lumber everywhere.

While we, Sydney, Hero and Hasty, chased the Bande Nere, the other three, Havock, Ilex and Hyperion dropped the boats and the wide-meshed nets overboard for the recovery of the survivors. We saved 525; 12 had to be transported on a stretcher, 4 did not survive and were buried in the sea off Alexandria and with military honours, 4 died as soon as they reached the port.

Not all the shipwrecked men sought salvation on board our ships, some of them, about fifty, wanted to swim to the coast not far away. I do not know if they succeeded. While recovering survivors, after a few hours, Italian bombers arrived from the Dodecanese, perhaps from Rhodes, who launched bombs without hitting the targets. Some fell near the Havock causing only negligible damage to the sides and a boiler. I am convinced that other sailors could have been saved.

Sydney, Hero and Hasty continued their gunfight duel with the Bande Nere. At 10.37, with only 10 of 6”shells available in the bow turret, Sydney was forced to abandon the pursuit and return to Alexandria to stock up on fuel and ammunition.

During the fight, the Sydney’s guns had fired 956 of 6”shells, with an average of 120 per weapon. The guns were so hot that the gunners were forced to cool them with water.

I had known that on the morning of July 20th the British bombed Tobruk using the Swordfish onboard the Eagle with the hope of finding the damaged Bande Nere. Their raid, however, caused the sinking of the destroyers Nembo and Ostro who were at anchor in the harbour and the steamer Sereno.

During the night the navigation was calm.

At 09.00 we met the Liverpool with the Admiral’s insignia. He had put himself to sea just to escort us in port as a sign of esteem for our work. We entered the port at 11.30. The crews of the units back from missions were on decks to receive the “welcome”. The ships in the harbour, including the French ones and a Japanese freighter, sounded their sirens. Even the Egyptians with their little boats had come to meet us. The Commander in Chief waited in his motorboat about 30 minutes before he could get on board. He wanted to be the first to congratulate us. It was not a good show to see the big hole in the funnel the splinter holes all over the bridge

The 4” turret had a hole on the steel serving platform; the safety depression gear of one of our guns was out of order; a sailor had been lightly injured in the shoulder by a splinter but recovered after a week of hospitalization in the infirmary. We received congratulatory messages from all the ships for the victory reported. And then, when we went ashore, wherever we were celebrated.

The naval battle lasted two and a half hours; the Colleoni sank in an hour and a half.

Our commander was awarded Commander of the Order of the Bath by King George VI.

The Colleoni commander, Novaro, died on July 25 on a hospital ship. At his funeral, according to the will of Admiral Cunningham, officers of the ships which participated in the battle were pall bearers, his coffin was placed on the gun carriage, he was buried with full naval honours. He was later buried in El Alamain’s Italian Military Memorial. ”

My sincere thanks to Mary Bell Nelson who has granted part of her father’s war diary to be inserted in my book “Granita al Gran Caffè”.

With pride I found the following note in Pietro Turi’s diary: “The chief carpenter 2nd class Michele Liuzzi of Taranto, wounded in several parts of the body, after being rescued from the enemy ship, claims that his companions were treated first”. Later I found the Citation of his Bronze Medal for Military Valour. It states: “… Wounded in several parts of his body remained in his combat post and required his superior officer being transported to the hospital due to his mortal wounds. Saved by an enemy unit following the sinking of his ship he worried that the wounded companions be treated before him and stoically endured the suffering. Example of high military virtue … “