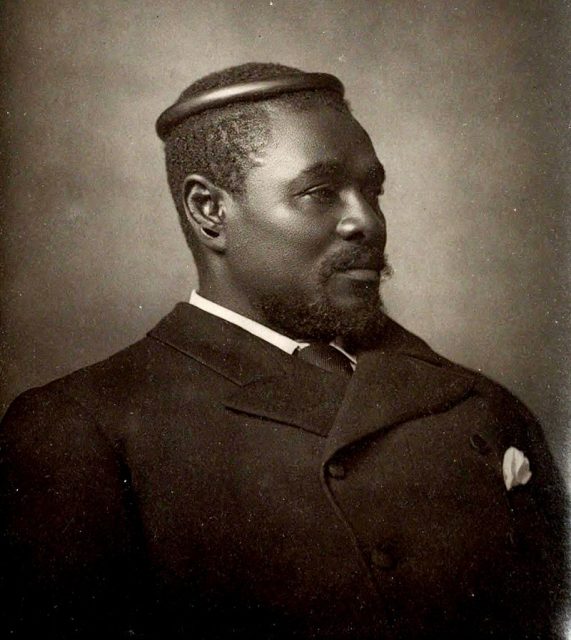

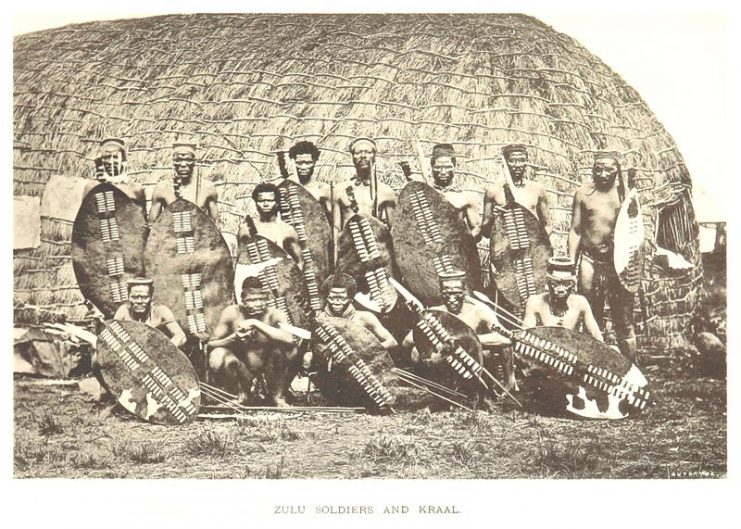

In response to the invasion of his territory, King Cetshwayo of the Zulu nation mobilized his army, a force of around 24,000 – 30,000 men.

January 22, 1879, is a date recalled with pride among Zulu historians and cultural custodians, for this was the day that the Zulu nation successfully and quite spectacularly defended itself against the colonial aggression of the most powerful empire in the world: Britain.

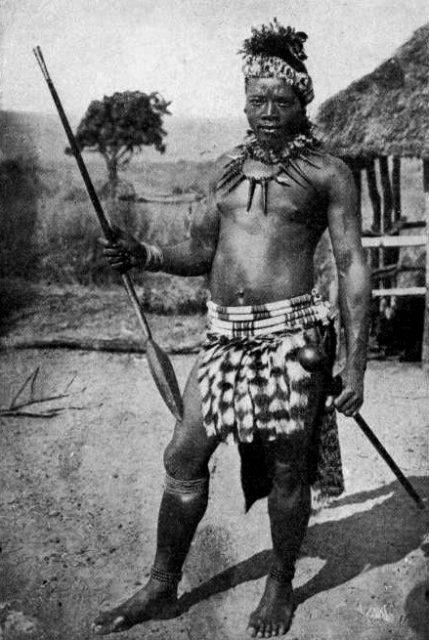

On this day, a Zulu army armed primarily with assegais (short stabbing spears) and cowhide shields utterly wiped out an invading British army column which was equipped with modern breech-loading rifles, artillery pieces, and Hale rockets.

This battle occurred on the slopes of Isandlwana, a large sphinx-shaped hill in Zululand (modern-day KwaZulu-Natal), South Africa.

The Battle of Isandlwana was the first major battle of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, which the British eventually won after this first initial and crushing defeat.

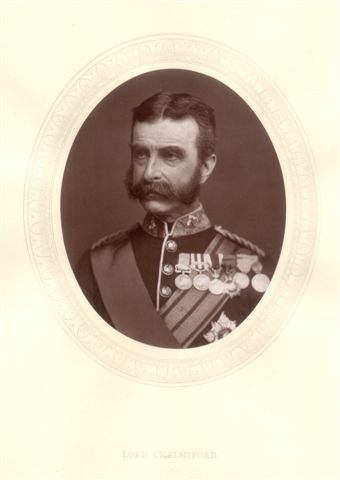

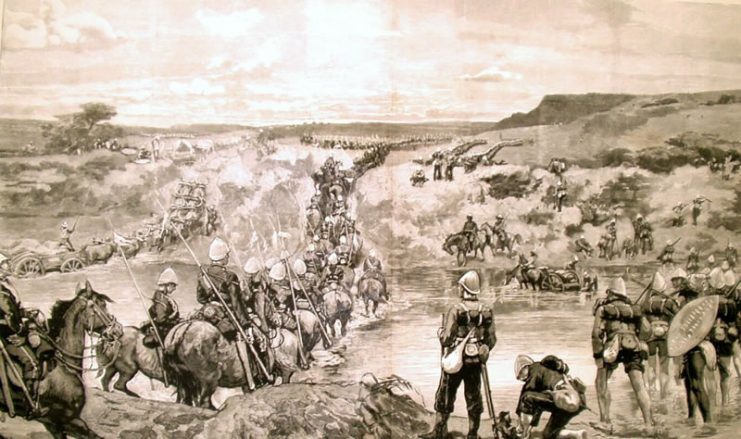

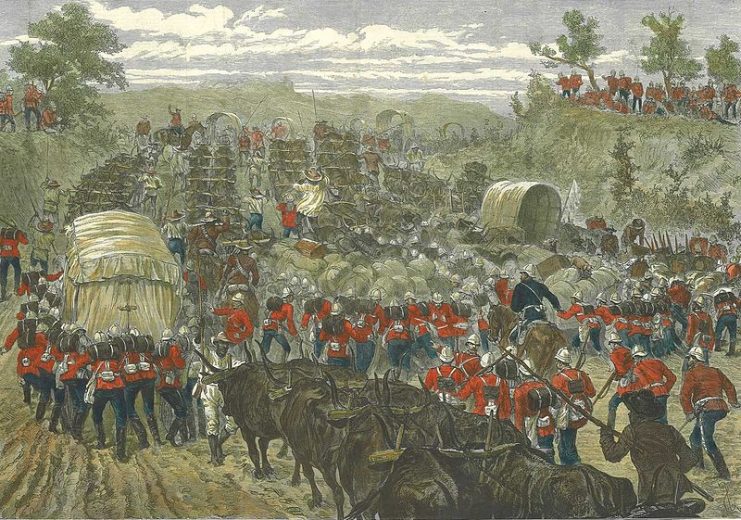

The British invading force consisted of a few thousand British troops as well as colonial volunteer troops and local native levies, all under the command of Lord Chelmsford. On January 11, 1879, they crossed the Buffalo River which marked the border between Natal (a British colony) and Zululand.

Chelmsford’s force formed the central column while two other British columns invaded Zululand from other locations. The regular British troops were, by and large, veterans of other colonial campaigns. They were confident in an easy victory over a technologically inferior foe.

However, they would be proved terribly wrong in this assumption.

In response to the invasion of his territory, King Cetshwayo of the Zulu nation mobilized his army, a force of around 24,000 – 30,000 men. While the men were essentially a militia force rather than a regular army, they were well-trained, highly disciplined, and brave. They were also tremendously physically fit and capable of covering many miles a day.

While they were primarily armed with assegais and cowhide shields, a few Zulus were armed with antiquated muzzle-loading muskets. Gunpowder and ammunition for these, however, were in very short supply, so the weapons played no significant role in the battle.

Chelmsford had divided his force into three columns to attack from separate directions. As such, the Zulu army was also divided into a few columns to deal with the invaders.

After an initial skirmish on the 12th of January with a small Zulu force who were quickly defeated by the British, Chelmsford took his force to Isandlwana, a large hill with a rocky outcrop shaped eerily like a sphinx. He and his men made camp there on the 20th of January.

His scouts reported seeing a large force of Zulus in the hills. Eager to find and fight the bulk of the Zulu army, Chelmsford divided his force and departed camp to seek them out, believing that it would be a simple task to crush the Zulu army and bring the war to a swift close.

He left 1,300 men, under the command of Colonel Pulleine, to defend the camp at Isandlwana.

What he did not know was that he had just been outmaneuvered by the Zulu commanders, who planned to attack and wipe out the reduced force at the camp now that they had tricked him into dividing his force.

The Zulus had planned to attack on the 23rd, but a chance discovery by British scouts of the main Zulu army – a force consisting of around 18,000 to 20,000 men – hiding in a valley near Isandlwana on the morning of the 22nd forced the Zulus into action earlier than they had anticipated.

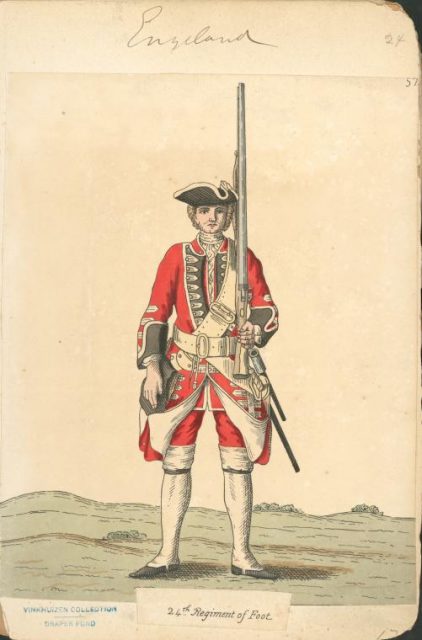

The men stationed in the camp at Isandlwana were mostly infantry troops, of whom the British regulars (some 800 men of the 24th Regiment of Foot) were armed with breech-loading Martini-Henry rifles and bayonets. There were also two seven-pounder artillery pieces, and a Hale rocket battery – Hale’s rockets being crude precursors to today’s guided missiles.

In addition, there was a force of mounted infantry consisting of indigenous troops under the command of a British officer, Colonel Durnford. These troops were well-trained, battle-hardened and extremely loyal to Durnford. There were also mounted colonists.

An auxiliary force of indigenous African troops was present, called the Natal Native Contingent. The British had not deemed these troops to be important enough to train properly, and they were armed mostly just with spears and shields, as the Zulus were. Only the non-commissioned officers (one man in ten) were issued with a muzzle-loading firearm and a handful of rounds.

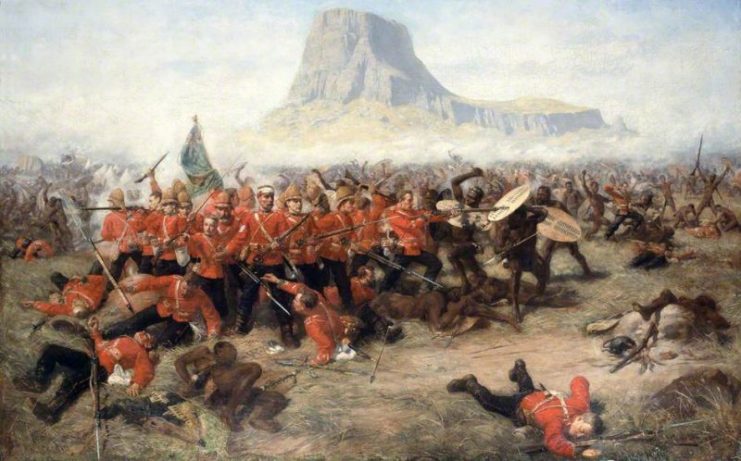

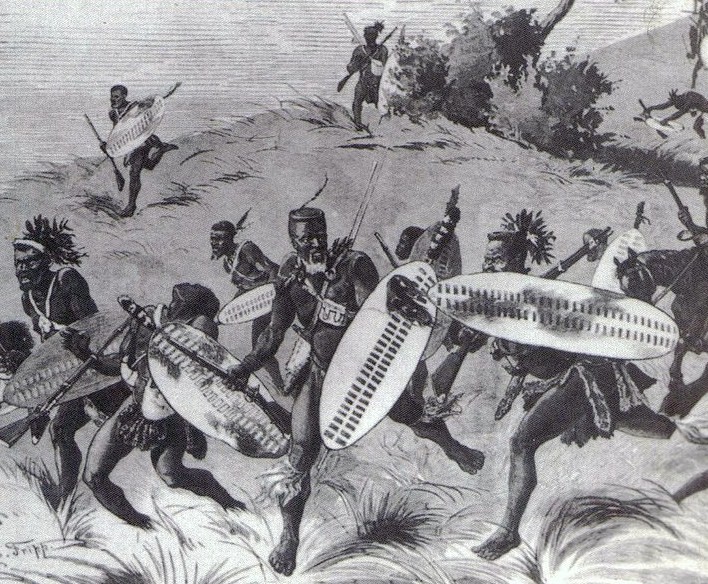

Once the bulk of the Zulu army had been discovered, they knew that they had to act. The Zulus began their advance toward the British camp, forming up into the traditional “horns of the bull” formation.

In this formation, two “horns” consisted of younger, faster troops who would sweep around to encircle the enemy’s flanks and eventually cut off any chance of retreat. Meanwhile, the “chest” of the army, consisting of the more experienced veterans, would engage the enemy head-on.

In this way, thousands of Zulu troops began pouring down off the Nqutu plateau onto the plain below Isandlwana.

The British had been given some pertinent advice by Boer settlers in Natal, who had plenty of experience fighting the Zulus. The Boers had emphasized the need either to engage the enemy from within a fortified position or to create a laager of ox-wagons (a closed circular improvised fortification) to protect themselves.

The settlers had suggested that it would be a very bad idea to engage the Zulus in open country with no fortifications – but this is exactly what the British did at Isandlwana, completely ignoring the advice they had been given.

The infantry formed up into spread-out lines far in front of the camp and commenced firing once the Zulus got within range. Durnford took his men out to the far right of the camp to try and stop the left Zulu horn from encircling them.

The Rocket Battery headed out to the very front and managed to fire one rocket at the Zulus. But they had not counted on the speed of the Zulu advance and were quickly overrun before they could fire again.

The men of the 24th kept up a disciplined and steady rate of fire. As the Zulus got closer, the heavy Martini-Henry rounds quickly began to take a heavy toll. The barrage slowed and almost stopped the huge Zulu army in its tracks to the point where many Zulus were lying down on the ground, frozen in their tracks or simply trying to crawl forward, hoping not to be hit.

However, the British could not keep up their fire indefinitely. As frantic calls were made for more ammunition, the Zulus began to press forward again. Durnford’s men ran out of ammunition and had to retreat, which created an opening for the Zulus.

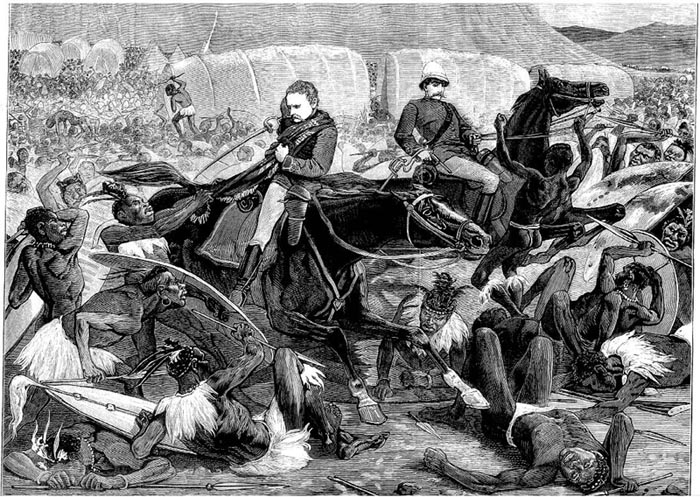

As Durnford’s troops were making a retreat, a Zulu regiment in the center jumped up and charged the British lines. They broke through them and, at that moment, all hell broke loose.

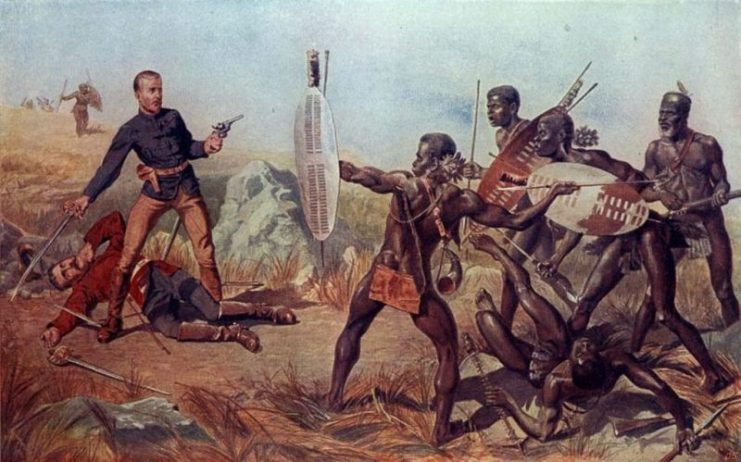

With a fresh injection of courage, the Zulu warriors began racing through the gaps while the desperate British troops tried to retreat in defensive squares towards the camp. Durnford and his men made a valiant stand near the camp to try to hold off the now-unstoppable Zulu charge long enough for at least some men to escape, but they were overrun and slaughtered.

The camp became a scene of savage anarchy, with British, Natal Native Contingent, and colonial troops fighting desperately for their lives.

The British, indigenous, and colonial troops formed up in defensive squares, fighting shoulder to shoulder as the camp was overrun. They fired off the last of their ammunition and then resorted to hand-to-hand fighting with bayonets, shovels, hatchets or whatever other improvised melee weapons they could get their hands on.

To compound the macabre atmosphere, there was a partial solar eclipse at the height of the battle. When combined with the billowing smoke from not only the rifle fire but also the tents and wagons that had been set on fire, the effect was to make the day darken dramatically.

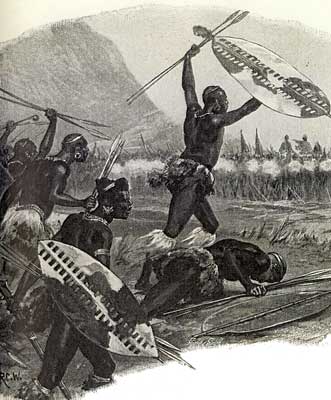

All around the camp men were falling, having been stabbed to death with Zulu assegais. It was clear that the British were done for. Those who were on horseback tried to flee, as did some men on foot, but they were all pursued and overtaken by the fleet-footed Zulu warriors, who cut them down.

A handful of mounted men made it to the Buffalo River, but many drowned in its swollen waters. Others were picked off by Zulus who had taken British rifles from their fallen foes.

In the camp, the few remaining British survivors gathered together at the foot of Isandlwana to make a final stand, firing off the last of their ammunition before charging to their deaths in a frenzy of hand-to-hand combat.

One last British infantryman of the 24th Foot held out for an hour or two by climbing into a cave on the rocky outcrop and picking off individual Zulus until his ammunition ran out, at which point he too was killed.

Read another story from us: Napoleon & the Zulus – Death of the Little Prince

The Zulus had won the day, and the British force had been slaughtered, almost to a man. As spectacular a victory as this was for the Zulus, though, it would not ultimately help them to win the war.

Thousands of Zulu warriors had been killed or severely wounded. Furthermore, the British called in more troops and brought in more weaponry over the following months. The final battle of the war was fought at the Zulu capital, Ulundi, in July, after which the Zulu kingdom was effectively destroyed.