The Napoleonic Wars of the 19th century were, in many ways, a precursor to the World Wars of the 20th century that would rock first almost the entire Western world with WWI, and then almost the whole world with WWII. Like the World Wars, the Napoleonic Wars involved many nations, had repercussions that were felt across the globe in an increasingly interconnected world, and changed world history in major ways.

The largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars was the Battle of Leipzig – also called The Battle of the Nations – which was fought from the 16th to the 19th of October 1813. It involved close to 600,000 men, many of whom were part of a huge multinational coalition force.

The French Army under Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig consisted of around 225,000 troops. In addition to French soldiers, it included troops from Italy, Poland and Germany. They all fought against the combined armies of the Sixth Coalition, which at this particular battle consisted of Russian, Swedish, Austrian and Prussian forces, and a British rocket brigade, altogether numbering approximately 380,000 troops.

The battle ultimately resulted in a French defeat. The 90,000 casualties at the end of the battle, along with the vast number of troops involved, made the Battle of Leipzig the largest battle on European soil prior to WWI.

From the outset, things were not looking good for Napoleon, who at the start of the battle was occupying the German city of Leipzig. Although this position afforded him numerous tactical advantages – the terrain was split by a number of rivers that converged here, and Napoleon controlled all of the bridges that crossed them – he was heavily outnumbered.

Also, after the decimation of his Grande Armée in Russia the previous year, the army he now controlled consisted largely of inexperienced, raw conscripts. In spite of this, he believed that superior tactics could win the day.

The opposing commanders, Tsar Alexander I of Russia (the supreme commander of the army), Emperor Francis I of Austria, and King Frederick William III of Prussia, were equally confident in their army’s ability to crush Napoleon’s forces, and with good reason. They not only outnumbered Napoleon in terms of men on the ground, but they also had twice as many artillery guns.

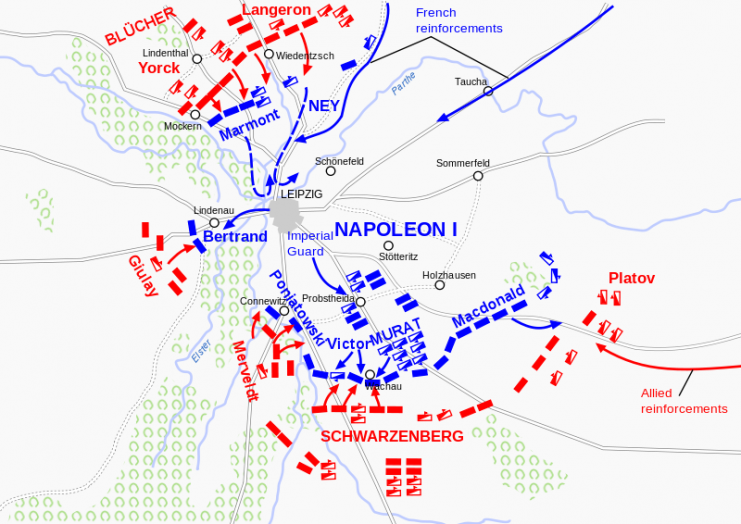

The battle began on the morning of October 16, 1813, with fighting taking place in a number of positions around Leipzig’s surrounds. The chief clashes occurred to the north, around the villages of Möckern, Groß-Wiederitzsch and Klein-Wiederitzsch, and to the southeast, in and around the villages of Markkleeberg, Dölitz and Wachau.

These battles involved everything from artillery bombardment, infantry maneuvers, and mass cavalry charges, to street-to-street fighting among the buildings of the villages. While the massive slaughter on both sides was bloody and the fighting furious, ultimately the day ended in a stalemate.

Compared to the slaughter and attrition of the 16th, the next day of the battle was relatively quiet. One of Napoleon’s soldiers, Lieutenant Parquin, a chasseur of the Old Guard, says that on the 17th, “the two armies confronted each other as if merely on dress parade” and did not engage, and that most of the French force “spent the entire day cleaning [their] arms and equipment.”

There was some action, however. Russian hussars charged a section of the French cavalry corps and drove the French cavalrymen back with force, smashing through their ranks and causing heavy losses.

By the 18th, Napoleon’s confidence had taken a serious blow. He realized that his army was on the verge of being totally encircled by the Coalition forces, and on top of this his men were running low on both supplies and ammunition. He attempted to sue for armistice, but his offer was rejected by the Coalition leaders.

The Coalition launched an all-out assault, which lasted for nine violent and bloody hours, and in which the French forces were driven out from the villages and other positions they occupied toward Leipzig. Probstheida, a village south-east of Leipzig saw some of the most furious fighting and most wanton bloodshed – here around 12,000 men were killed in under three hours.

Some of the fighting on the Coalition side involved the Bashkirs, Russian steppe warriors who were descendants of Genghis Khan’s Mongol hordes. These warriors, dressed and armed in a remarkably similar fashion to their Mongol ancestors of five hundred years prior, fought in the same way as those ancient warriors had. On horseback, they attacked the French as mounted archers, whooping out war cries and firing swarms of arrows into the French ranks.

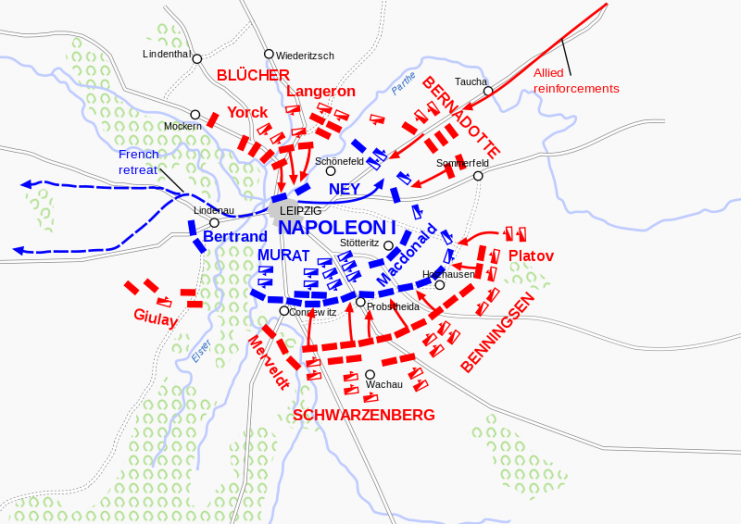

In addition to the carnage wrought by the fighting, Napoleon suffered more losses on the 18th through defections: two Saxon brigades deserted and joined the Coalition. Their defection left a huge hole in the French lines which the Coalition was able to exploit.

The French were not about to hand the Coalition an easy victory though, and they fought tooth and nail to hold their ground, generally only ceding it when they ran out of ammunition or were completely overrun.

Despite their valiant spirit, however, by the end of the day it was apparent that the battle was lost. The numbers of the Coalition were simply too great, and the French were now running dangerously low on ammunition.

Napoleon’s only real option at this stage was to try to salvage as much of his force (and pride) as he could through a fighting retreat. He ordered a retreat, wherein his troops would gradually withdraw to the west, across the Elster River. The retreat started that night, with troops being pulled back with as much stealth as could be managed, in order that the Coalition not discover their movements.

On the morning of the 19th, however, the Coalition became aware of the French retreat, and launched an all-out attack against the French forces from the south, east and north. The retreat through Leipzig was marked by fierce urban fighting, with combat occurring from building to building and on the streets of the city.

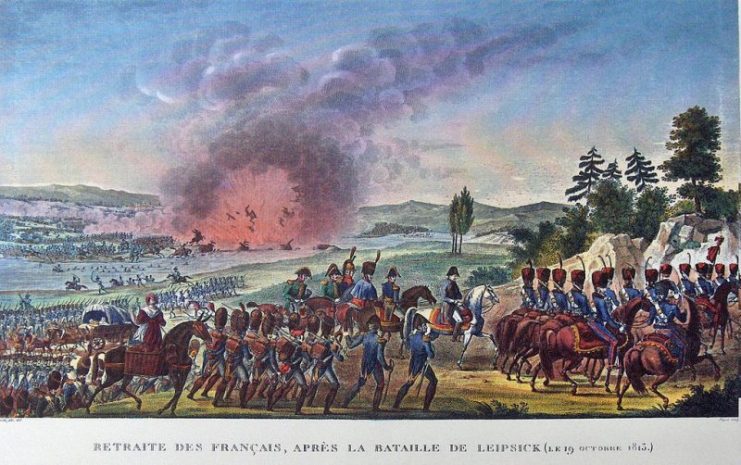

The retreat was marked by a particularly tragic disaster for the French. Napoleon ordered the bridge over the Elster River to be demolished, to prevent the Coalition troops from pursuing the French any further. Due to a bungling of information when the order was passed down the chain of command, however, the bridge was blown up while French troops were still crossing.

The resulting explosion killed many troops, but even worse, it cut off the rearguard French force and left them stuck in Leipzig, which was now swarming with Coalition troops. The French, realizing that they would likely die that day, barricaded themselves into whatever buildings they could, and fought on in pockets of desperate last stands until they ran out of ammunition. Almost all of them were slaughtered.

Many other troops drowned while attempting to swim across the Elster River after the bridge was destroyed. Even those who survived the swim were not safe – many were killed by Coalition sharpshooters, for whom the stragglers, struggling up the muddy banks, were easy targets.

The remnants of the French force retreated toward the Rhine, having suffered a decisive and demoralizing defeat.

Read another story from us: Best Generals in the Napoleonic Wars

All in all, around 90,000 men were killed over the four days of fighting. Estimates range from around 38,000 on the French side to over 54,000 on the Coalition side that were killed, wounded or missing. There were so many casualties that locals found it impossible to dispose of all the bodies, and many corpses were still out in the open the following year.

The Battle of Leipzig was thus the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic Wars, and an ominous harbinger of the mass death, violence and destruction that was to come a hundred and one years later, when the First World War broke out.