On September 10, 1547, the national armies of England and Scotland fought in a pitched battle at Pinkie Cleugh. Though no one knew it at the time, this would be the last such battle in the two nations’ long history of bloody relations.

The End of Peace

When King Henry VIII of England died in January 1547, he left an uneasy truce with the Scots. Though the Scots had already rejected parts of the agreement, the frailty of their leading ally, King Francis I of France, helped to keep the three nations from war.When Francis followed Henry to the grave a few months later, the delicate balance crumbled.

The terms of the truce had bound the infant Queen Mary of Scotland to marry King Edward VI of England, himself only nine years old. Emboldened by the support of the new French King Henry II, the Scots rejected this deal, which would lead them to subservience to the English throne.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Somerset, made Protector of the Realm because of Edward VI’s minority, built his foreign policy around uniting the two countries to create a stronger position against the French.

Throughout the summer, Somerset dithered between raising an army and seeking a peaceful solution, while French forces intervened in support of anti-English elements in Scotland.

At last, in late August, Somerset committed to the path of war. He assembled an army in Newcastle, ready to head north and bend Scotland to his will.

War Drums

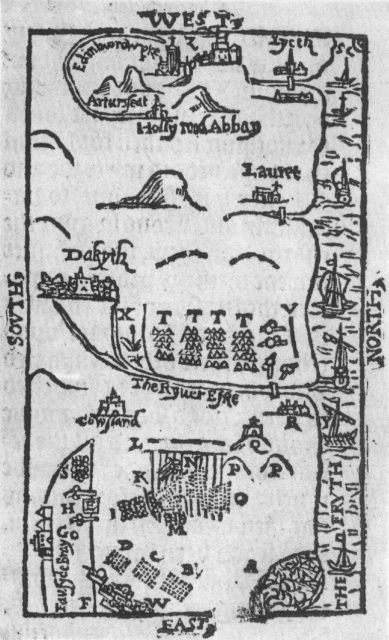

On September 1, the English army crossed the border into Scotland.

The army wasn’t huge but was well-balanced and well supported. It totaled around 16,000 men, a quarter of them cavalry, with eighty cannons, and hundreds of carts and wagons in its supply train.

A fleet under Lord Clinton sailed up the coast parallel to them, carrying more supplies.

The Earl of Arran, commander of the Scottish forces, had a far larger army of around 25,000 men.

On the downside, he had far fewer cavalry and artillery. He also could not be sure about the reliability of everyone serving under him, given recent violent divisions within Scotland.

On September 8, the English reached high ground overlooking flat land east of the River Esk. On the far side of the river, the Scots waited for them, skillfully arrayed for battle. The Scots held strong positions which the experienced Somerset knew he could not take in a frontal assault.

On the 9th, the Scottish cavalry crossed the Esk and maneuvered in front of the English, hoping to draw them out. Somerset held his cavalry back until the Scots were turning to retreat, then attacked.

Outnumbered and caught off balance, the Scottish horsemen were badly mauled, leaving Arran without an effective cavalry force.

Peace talks that afternoon led to nothing, as the two sides had such opposing aims. The stage was set for a pitched battle.

The Battle

At eight the next morning, Somerset advanced off the high ground, bringing his heavy guns forward to threaten the Scots. The destruction of Arran’s cavalry allowed him to risk exposing his left flank so he could threaten the Scottish left.

The reasons for what followed have been debated, but Arran was probably motivated by two factors.

Firstly, the English were advancing towards Inveresk Hill, which would give their artillery a perfect position to bombard the Scots. Secondly, the sight of invading English troops enraged the Scottish soldiers, making it nearly impossible to hold them back.

Starting with a force of Highlanders, the Scots advanced through heavy rain across the Esk. In doing so, they gave up their strong positions and were forced to face an army that, while smaller, had more artillery, more cavalry, and more freedom to organize itself before they clashed.

Those first Highlanders were driven back across the river by English artillery. Meanwhile, the rest of the Scottish infantry, having made their way across, formed their traditional formation of the schiltron – a bristling mass of polearm-carrying men.

Armored in steel and leather, carrying long pikes, the Scots formed an impressive formation, intimidating to infantry and invulnerable to cavalry.

Somerset initially attacked with infantry and cavalry. It was a costly assault that made no dent in the Scottish formation, but it was blood well spent. It held the Scots in place while Somerset moved his artillery to close range.

Now the disadvantage of the schiltron made itself felt. Closely packed together, the Scottish infantry were very vulnerable to ranged attacks, particularly from artillery. Somerset set his cannons, archers, and mounted Spanish arquebusiers to rain fire down on the Scots.

The cannons were particularly devastating, their shot tearing paths of destruction through the pikemen.

As the Scottish lines weakened, Somerset watched for his opportunity. Once the enemy were completely off balance, he attacked with his cavalry once more. This time, the Scots could not stand.

The Earl of Angus tried to make an orderly retreat on the right, while the center collapsed into chaos. Soon, retreat became rout, the whole army fleeing across the river.

The English, their discipline collapsing, chased the Scots, hacking them down as they ran. It took hours to regain control, during which time the slaughter was terrible. Around 10,000 Scots died. Many important nobles were killed or captured.

The English lost around 500 men, mostly from their heavy cavalry – a fraction of the Scottish losses. The road to Edinburgh lay open. But rather than march north and seize Queen Mary, Somerset consolidated his hold on southern Scotland.

This gave the English a strong position in the short term, but lost them the chance to secure Mary and Edward’s marriage and so achieve a lasting victory.

Other wars would occupy the English and Scots for the rest of the century. Then, in 1603, they were united peacefully when James VI of Scotland inherited the English throne as James I.

Though Scots and Englishmen would fight again, Pinkie Cleugh was the last time their national armies faced each other in pitched battle.

It was a sorry end, one side suffering terrible slaughter, the other failing to maximize the advantage it had gained. But though only the passing of decades would make it clear, it was at least an end.