If you were asked to picture an average sixteen-year-old British boy, you’d probably imagine a kid who goes to school from Monday to Friday, and who spends his weekends messing around on his phone, listening to music, playing on his Xbox One or PS4, and probably wasting a lot of time on social media.

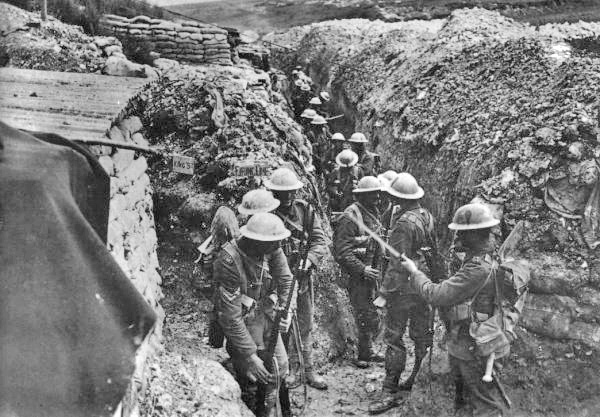

One hundred years ago, however, hundreds of thousands of boys just like this imaginary one had rifles and bayonets in their hands and steel helmets on their heads – and they were fighting and dying in the trenches of France.

Wars throughout history have mostly been fought by young men – men in the prime of their physical health, at peak levels of strength and endurance. While this fact is necessitated by the physical demands of warfare, it nonetheless makes for tragic outcomes as war cuts short many young lives, and it is even sadder when children get caught up in it and end up suffering and dying.

It is a widely-known fact that most armies of the modern era have included a number of soldiers who were in their teens, having lied about their real age to bypass minimum age limits for soldiers, but what is perhaps not so widely-known is the massive scale at which this occurred, particularly in the First World War.

In the British Army of the WWI era, for example, it has been estimated that around 250,000 boys under the age of eighteen fought and died for their country.

While the bulk of these boy soldiers were in their late teens, and thus close to the minimum age limit of eighteen (to enlist, but they had to be nineteen to fight on foreign soil), others who were far younger ended up in the trenches. Indeed, the youngest soldier to have fought in the extremely bloody and drawn-out Battle of the Somme was reported to have been a mere twelve years old.

The memory of this child was recalled by another boy soldier, George Maher, who was barely into puberty at the time he was a private fighting in the trenches. Maher was only thirteen at the time, and he said that the twelve-year-old couldn’t even see over the top of the trench. Maher ended up breaking down in tears when the trench was shelled, and he and five other underage boys were hauled out and sent home.

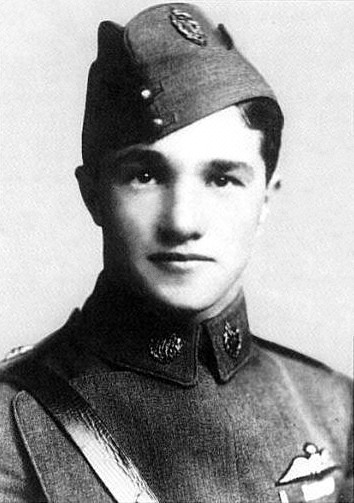

A more tragic story of an individual boy soldier was that of Aby Bevistein, who changed his surname to “Harris” when he enlisted at the age of fifteen. After surviving months in the horrific trenches of the Western Front, he was injured by a mine exploding, and also suffered from what we would now know as PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder), but what was then simply termed “shock.”

After a recovery period in a hospital for his wounds, he was sent back to the front lines. A few months later, the Germans attacked the trench in which he was stationed with grenades. Disoriented and confused, he wandered aimlessly back and forth between the British lines, and was then arrested and charged with desertion. He was later executed for his supposed crime – at the age of seventeen.

While it is inevitable that some underage soldiers will manage to sneak their way into any army – teenagers have always proved adept at sneaking into places where they are not supposed to be – one has to wonder how such a vast number of teenage boys ended up getting into the British Army at the time of WWI without attracting a lot of attention and publicity.

There are a few reasons that so many boys were able to bypass the legal age limit for fighting overseas. Firstly, there was the fact that a lot of soldiers needed to be mobilized at short notice. At the time WWI broke out, Germany had an army of 3.7 million men, while Britain had around 700,000.

A storm of intense patriotic fervor gripped the nation, and young men – including hundreds of thousands of underage boys – lined up in droves to serve their king and country, not knowing a thing about the horrific realities of warfare that awaited them across the ocean.

Secondly, record-keeping was nowhere near as strict and comprehensive a hundred years ago as it is in today’s digital age, and bureaucracy was not nearly as pervasive as it is now, so it was a lot easier for young men to lie about their age at that time.

Thirdly, many recruiters were more concerned with the recruits’ ability to meet the minimum physical standards of at least five foot three in height, and a chest of at least thirty-four inches, than they were with strict age limits. As long as a young man was physically large enough and keen to fight, many recruiters were fine with turning a blind eye to the fact that the recruit was obviously underage.

Sadly, many recruiters were motivated by pure greed, too. They were paid two shillings and sixpence, equivalent to about £6 in today’s money, for every man that successfully signed up, so they could make a lot of money by letting in pretty much anyone who satisfied the physical requirements.

Finally, much of the motivation for underage boys to enlist came from the circumstances of the boys’ lives. Many ran away from home to escape unhappy home lives, or enlisted because they saw the army as a ticket out of dire poverty or other situations of hopelessness. Others lusted for adventure, having little idea of the horrors that lay ahead.

Others were pushed by family, schoolmasters and even priests to enlist as a way of toughening them up and getting to learn about duty and responsibility. None of those pushing the boys to enlist had much idea about the realities of warfare.

Attitudes toward the boy soldiers and their place on the battlefield did change, however, as WWI progressed. As the public became more aware of the scale of carnage and the brutality of the war, there was a swing in public opinion and many people began to demand that boy soldiers be removed from the front lines and sent home.

In 1916 the War Office acquiesced and said that if parents could prove their sons’ ages with a birth certificate, they could have the boys removed from the front lines and sent home. Nonetheless, many of these boy soldiers ended up staying at the front and fighting in the savage battles of the First World War right up until the end of it in 1918.

Read another story from us: The Youngest Soldier In WWI Was A Serbian Boy, Aged 8

Those who survived made it home, having done a lot of growing up in those terrible years and having seen, experienced and survived things that most men three or four times their age would not have lived through.

The end of the First World War was not to be the end of child soldiers fighting in wars, of course, as this has continued until the present day, but it was, thankfully, perhaps the final instance of the presence of underage boys in such vast numbers on the battlefields of war.