Great Britain’s colonialism in the 19th century is an action the country is still answering for today. Back then, it considered itself very much entitled to interfere in the affairs of other nations, particularly those over which it had ruled for decades.

English attitudes about Sudan, for example, were especially negative in the 1890s, and the British felt they were justified in dictating civic policies. In order to regain the control they had lost in the previous decade, as well as enhance its power in nearby Egypt, the government ordered military action.

The British were nervous about their own level of influence in the area, as well as about French expansion. The two countries were distrustful of one another, and on the brink of a cold war, 19th-century style. Sudan became a pawn in their political one-upmanship.

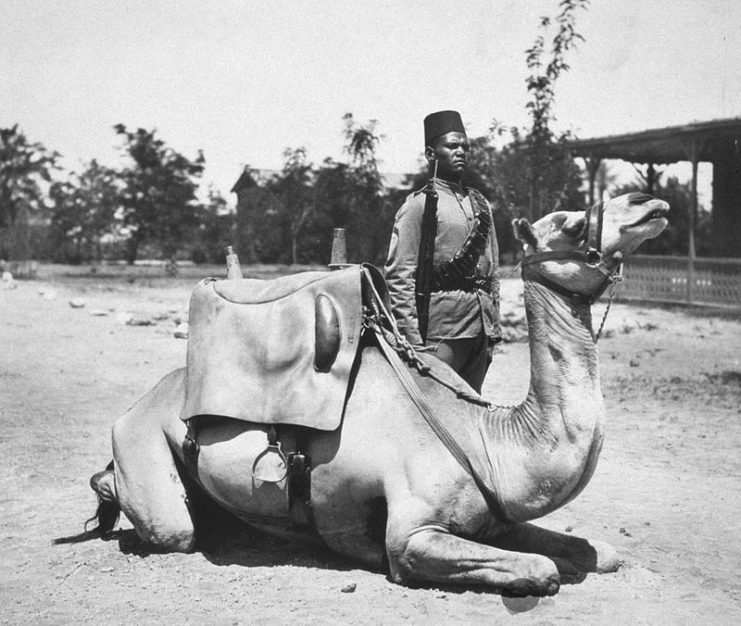

The army Great Britain sent in was Anglo-Egyptian. Some were experienced soldiers, some not, but they were armed with the latest in military weapons.

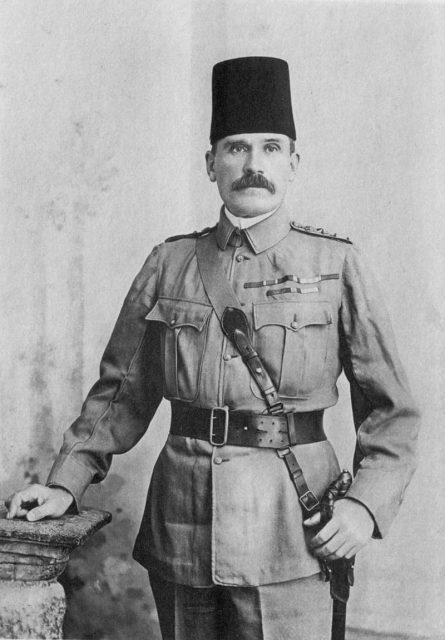

In 1898, Major General Herbert Horatio Kitchener had his men build the Sudanese Military Railway, with the express purpose of getting troops as close as possible to Omdurman, in central Sudan.

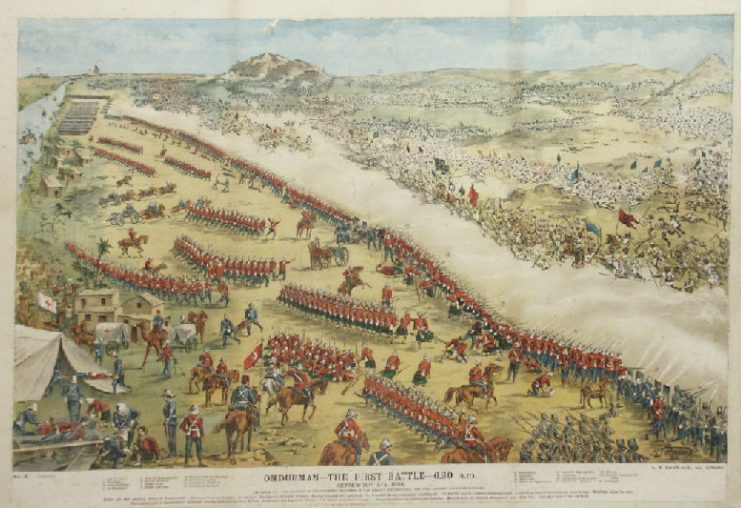

Kitchener sent men to investigate the terrain around Omdurman, then promptly bombed it. But when Kitchener saw approximately 52,000 Mahdist infantry emerge from the town, he pulled his men back immediately. Although the enormous Mahdist force also had a cavalry of about 3,000 men, it was hampered by its old weapons.

By the onset of September, Kitchener was rethinking his strategy. He made camp close to the edge of the Nile, just a short distance from Omdurman. He ordered his men into a half circle, and had them probe the river’s darkness, and the surrounding territory, with massive lights.

Kitchener knew that if his forces were set upon in the pitch black of night, they would be unable to defend themselves.

He was determined they would remain vigilant. They may have had modern weapons and skilled personnel, but those would be useless if they fell prey to an attack in the middle of the night.

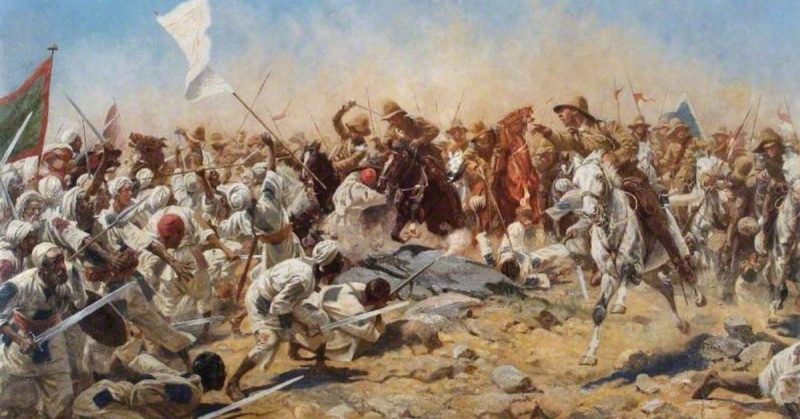

As day broke, Sudanese forces bore down heavily on the British soldiers. The Anglo-Egyptian army fired back with everything from rifles to machine guns. It was like shooting fish in the proverbial barrel.

The Mahdists hastily retreated, but they had not given up yet. Kitchener called upon the 21st Lancers to go after them. In charge was Colonel R.H. Martin, who quickly led his men in pursuit of the enemy.

But the Sudanese soldiers caught them in a surprise attack, and the opposing forces locked in brief, bloody, close combat. Three British soldiers were later awarded the Victoria Cross for their participation in this part of the fight.

The British then gathered together to head for Omdurman, which was about seven miles away.

During this trip, they lost their unity and focus, which made them again fall prey to the Mahdists. Brigadier General Hector MacDonald was able to repel attacks from all directions, and thanks to his strategies, the British were able to take Omdurman.

Although it was a big win for the British in many ways – they lost only 48 men – the public back home was growing weary of the violence that always seemed to accompany colonialism. Their forces had killed about 11,000 Sudanese men, and some wondered if the conflict was worth the price.

When the press broke the news that British soldiers had defiled a Mahdi sacred tomb, many were outraged. Furthermore, word spread that British personnel had bayoneted Sudanese men who had fallen in battle but not died. Many decried the acts as neither honorable nor British, but rather as savage.

The British Empire would continue, of course, for many years to come. But the Battle of Omdurman illuminated a shift taking place in the public’s mind: if Great Britain had to kill so many people, if it had to interfere and insist it knew best no matter what the country or culture, was it right? Was it fair? Was it proper?

Those questions – and many others like them – would preoccupy Great Britain and its people for many years to come.