During the early 1940s, the British military was looking for a way to quickly end the Second World War. This led them to look into the use of biological warfare. They developed a plan which included the use of anthrax, but the proposed attack never happened. Unfortunately, its testing left a Scottish island uninhabitable for decades.

The launch of Operation Vegetarian

Throughout the early years of WWII, the Allied forces feared the use of chemical weapons by the Axis powers, given the use of mustard gas during World War I. The use of such weapons during the Great War led the British War Office to open an Experiment Station at Porton Down in southern England, which remained open after the conflict. While “germ warfare” was prohibited under the Geneva Protocol, research was not.

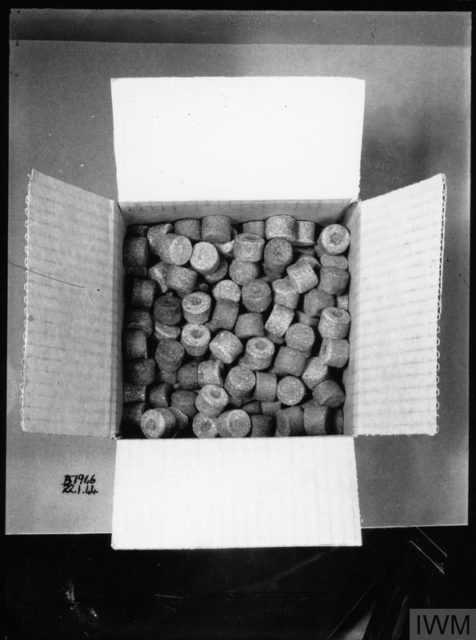

In 1942, the British military hoped to create its own chemical weapons to use against the Germans. The plan was to airdrop linseed cakes laced with poison over German cattle fields, with the aim of creating a countrywide food shortage. The subsequent human infections caused by the poison would also result in mass casualties, potentially putting an end to the war.

It was eventually decided that anthrax would be used to lace the cakes – more specifically, Vollum 14578, a highly virulent type. While anthrax, in general, is lethal, this particular strain was known for becoming more harmful as it spread, meaning a localized outbreak could quickly become a city and nationwide one.

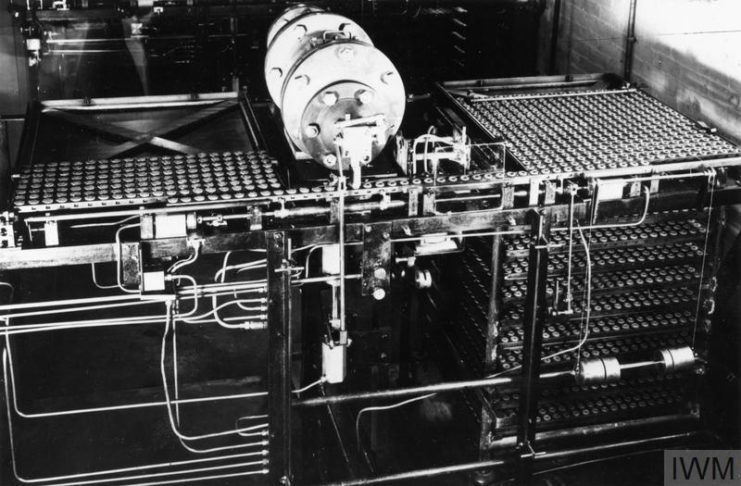

The goal was to produce 5.3 million cakes by April 1943. A baking company in northern England was commissioned to make the linseed cakes, which a soap manufacturer cut into the appropriate size. What needed to be tested was the actual anthrax, leading to the acquisition of Gruinard Island, off the coast of Scotland.

Biological testing on Gruinard Island

Once the British government had acquired the uninhabited Gruinard Island from its landowners, a plan was put in place to begin testing. Meteorologist Sir Oliver Graham Sutton was put in charge of a 50-man team, and David Henderson took charge of the anthrax “bombs.”

Between 60 and 80 sheep were brought over to the island and separated into “exposure crates,” which were covered in cloth to prevent cross-contamination. Once they were separated, tests began. 30-pound bombs were dropped, bursting into a cloud of deadly dust that drifted down onto the farm animals. This type of testing continued into the summer of 1943.

During this time, stories of dead animals washing ashore on the mainland began to spread. The War Office attributed this to a Greek freighter in the area, saying its crew was throwing rotten animal carcasses overboard. Local farmers who lost their livestock to sudden illnesses were compensated, with an official from the War Office being posted at a hotel to settle claims.

The testing showed that the chemical weapons had the power to contaminate whole German cities and make them uninhabitable for decades. However, by the time this was concluded, the war had gone in a different direction. The Allied forces had since landed in Normandy and were making significant gains against the Axis powers in Europe. This meant biological warfare against Germany was unnecessary.

Decontamination of Gruinard Island

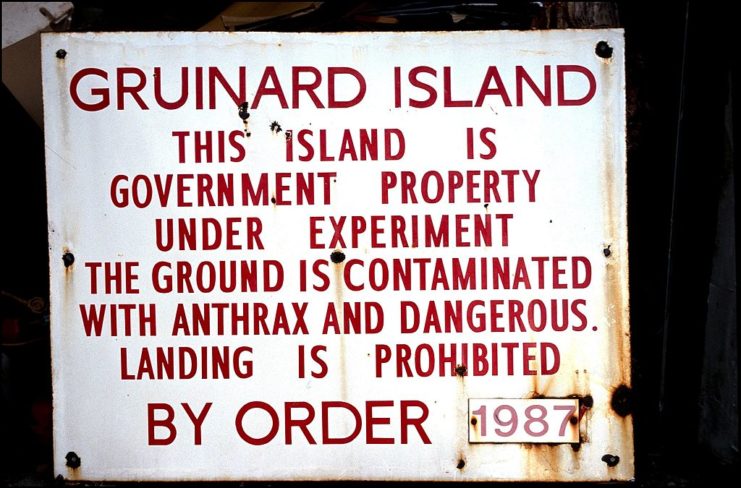

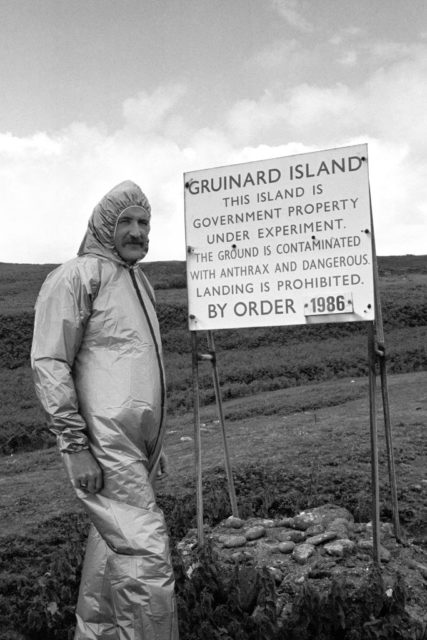

Following WWII, Gruinard Island was deemed too contaminated to be habitable, leading the British government to indefinitely ban public access. While it had been assumed the island would remain so for only a decade, the anthrax levels didn’t decrease.

In 1981, a terrorist group used the island’s anthrax-laced soil to wage terror on those in public office. Called “Operation Dark Harvest,” it began with messages being sent to British newspapers, calling on the government to decontaminate the island. The notes also said that a “team of microbiologists from two universities” had traveled to the island and collected 300 pounds of soil, which were subsequently sent to facilities across the United Kingdom.

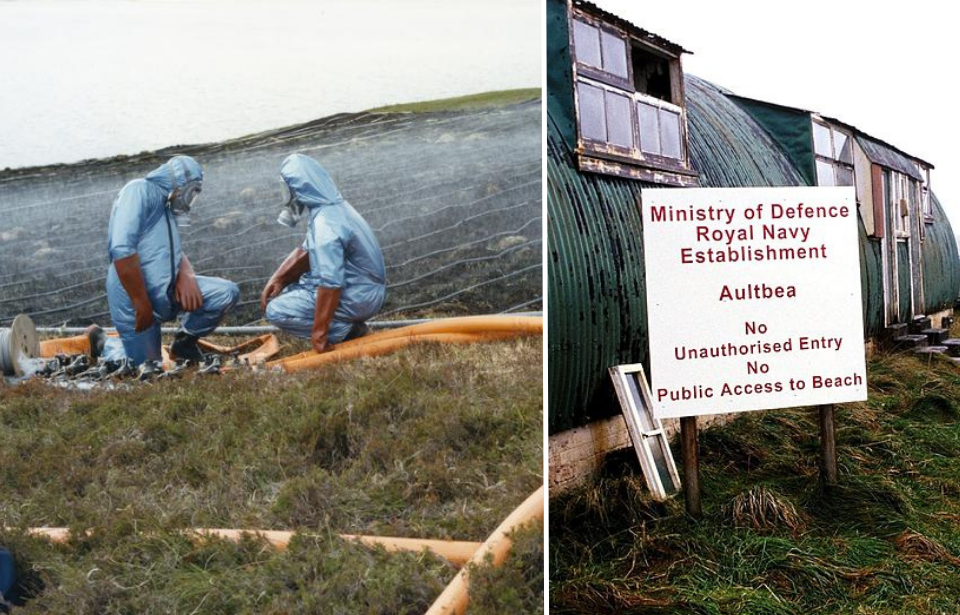

In 1986, cleanup work began on Gruinard Island, with 280-tons of formaldehyde diluted with seawater being sprayed over its 196 hectares. The worst-contaminated topsoil was removed. Following this, a flock of sheep was placed on the island to allow scientists to monitor anthrax levels. In 1990, the island was deemed “safe” and sold back to the heirs of those who’d sold it to the government during the war.

Since 2007, there has not been a recorded case of anthrax poisoning, based on tests conducted on the island’s sheep. That has not convinced everyone, with some believing it’s still too unsafe for people to visit.