Sir Alexander Korda is being honored this month by the British Film Institute (BFI). Highlighted in the retrospective are some of Korda’s most recognized films which were popular around the world in the 1930s and 1940s.

The films being shown include newly restored versions of The Private Life of Henry VII and The Thief of Baghdad which won an Oscar.

But BFI’s season for Korda doesn’t stop with his impressive cinematic portfolio. The Institute is also making viewers aware of the other side of Korda – the Hungarian Jewish emigré who managed spies for the British government during World War II.

In the late 1930s, Korda employed a screenwriter named Winston Churchill whose political career had stalled. That relationship helped influence Korda’s life during the war.

Korda was born in 1893 in a small village in Hungary. His birth name was Sandor Kellner. He attended a Jewish school until he was eight.

He claimed to be a member of the Hungarian Reformed Church when he was an adult, but he was not shy about bringing up his Jewish background when dealing with Hollywood tycoons like Sam Goldwyn.

His Jewish ancestry was certainly a driving force in his life once he learned about the anti-Semitic influences in Europe and the atrocities being committed against Jews.

Korda was a unique talent in the film industry. He wrote the screenplays that he directed, built movie studios, and produced. He even married three actresses along the way.

Korda began working in journalism when he was 18. He did not serve in World War I due to poor eyesight. Instead, he began a film magazine and made some documentaries.

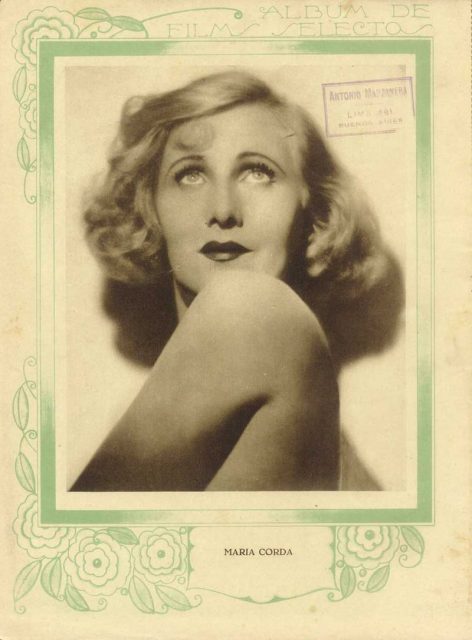

By the time 1919 came around, he was known in Hungary for his feature films. He married the star of one of his movies, Maria Corda (nee Farkas). The filmmaker helped her become one of the top film stars in Europe.

Then the “Counter-Revolution” occurred in Hungary and Jews became hated there. In October of 1919, Korda was arrested. His wife and his brother begged for his release.It was common for Jews to be executed after being arrested. But somehow, Korda was released, and he fled to Vienna with his wife.

Korda began making films, often with his wife as the star, first in Vienna and then in Berlin. But the two of them were looking beyond Europe to Hollywood.

Maria was convinced that the Americans wanted her as a big film star and they were giving her husband the chance to direct a few films as an incentive for her to move. In truth, Hollywood wanted Korda, the director, and they were willing to take Maria as part of the deal.

But the couple became disillusioned with Hollywood. Korda was bored with the films he was given to direct while Maria was upset with the small roles they gave her to play.

In the end, Korda was fired for stubbornly insisting on doing things his way. He and Maria divorced in 1930.

In 1931, Paramount sent Korda to England to work on a film for their new production unit in that country.

This was the beginning of his appreciation for Britain. It also began his string of successful movies.

His first British film, The Private Life of Henry VII, won Charles Laughton an Oscar for his work in the title role. This made it the first movie not made in Hollywood to get an Oscar. It also became the highest grossing British film of its time.

Korda was able to open his own company, London Film Productions, and build a studio in Buckinghamshire.

In 1937, Korda began working with the government to use his film company as a cover for British spies. The spies would travel through Europe while “working” as screenwriters or film researchers for London Film Productions.

Korda also gets some credit for nudging the US into WWII. He made a well-received propaganda film called That Hamilton Woman which is said to be Churchill’s favorite film.

Korda was knighted in 1942. It was an honor for a man who helped to develop the British film industry. But it was also recognition for his assistance during the war.