Airship travel is one of the technologies that designers keep returning to, believing its potential has yet to be fully realized. Even today the British 302-feet long Airlander is an example of how designers are still pushing the limits what an airship could achieve.

Back in the early 1930s many nations were pressing ahead with various airship projects and innovations, despite disasters such as the 1930 British R101 crash in France that killed 48 crew members and passengers. In the US, military officials believed that the airship’s long range and low running costs could give it an invaluable role in the nation’s defense.

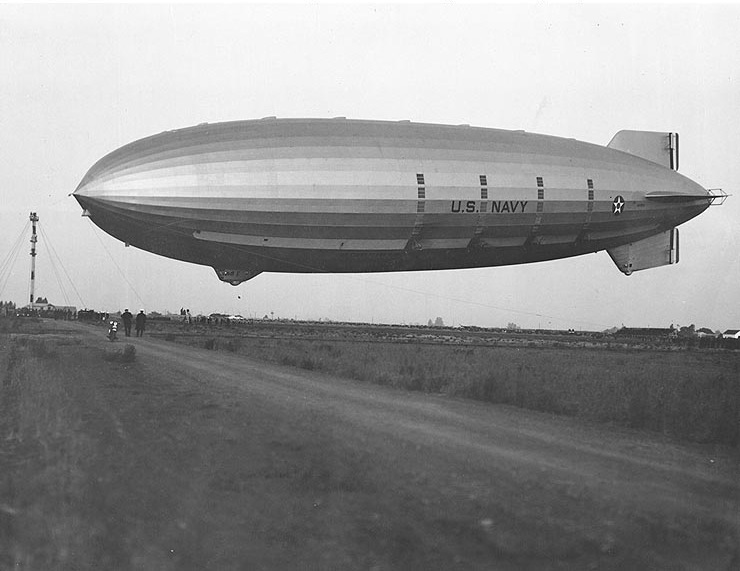

With that in mind, in the early 1930s the Americans developed the Akron class of airship. Consisting of the USS Akron and her sister ship the USS Macon, both were designed and built by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation at its newly completed Airdock facility in Akron, Ohio.

These airships had a crucial change compared to earlier airships: they used expensive helium rather than hydrogen gas, as it was non-flammable and therefore safer.

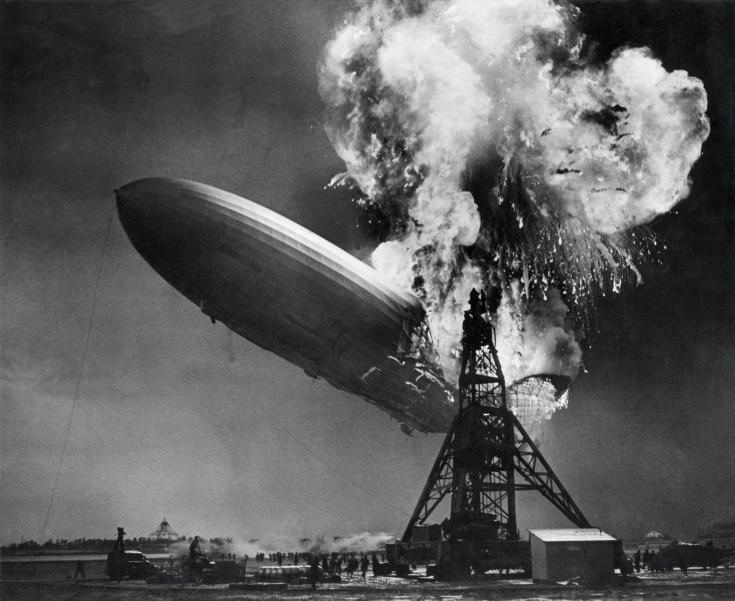

Another factor that influenced this decision was that the United States was the largest producer of helium in the world. This guaranteed a strategically secure supply of the gas—something the Germans did not have, which forced them to make the disastrous decision to continue to use hydrogen in their airships. This would lead to the Hindenburg airship disaster of 1937 that resulted in the airship being engulfed in flames and killing 36 people.

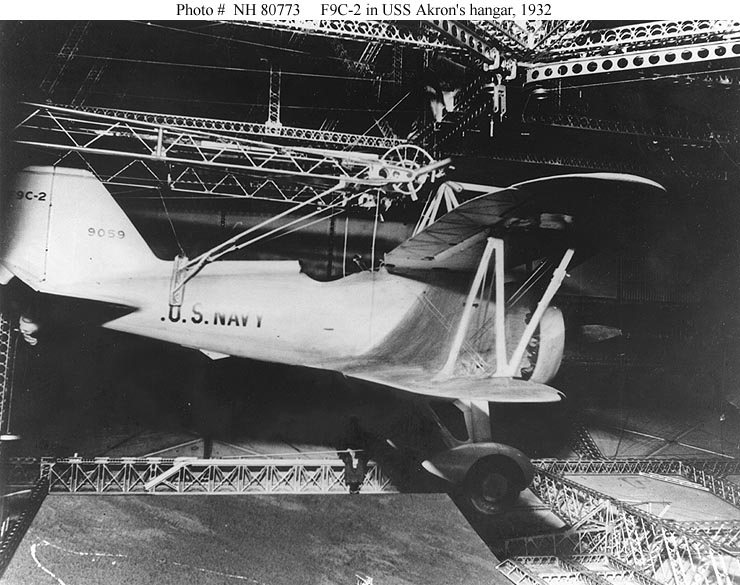

The US Navy saw a further potential for airships that others had not, which was to develop airships into aerial aircraft carriers.

The USS Akron was commissioned in October 1931 and followed by the USS Macon in June 1933. Each was truly huge at 785 feet long, which is over three times longer than a Boeing 747 airliner.

They displaced nearly seven and half million cubic feet of volume and could carry up to five small fighter-reconnaissance aircraft. They launched and retrieved the planes one at a time via a trapeze-style mechanism.

Both bristled with 8 heavy machine guns, had a crew of 60, and a range of nearly 7,000 miles. And with a top speed of 79 miles per hour, they were twice as fast as the latest American Lexington-class aircraft carriers.

The role of these airships was to scout for enemy ships and submarines, primarily with their aircraft which were Curtiss F9C “Sparrowhawk” biplanes.

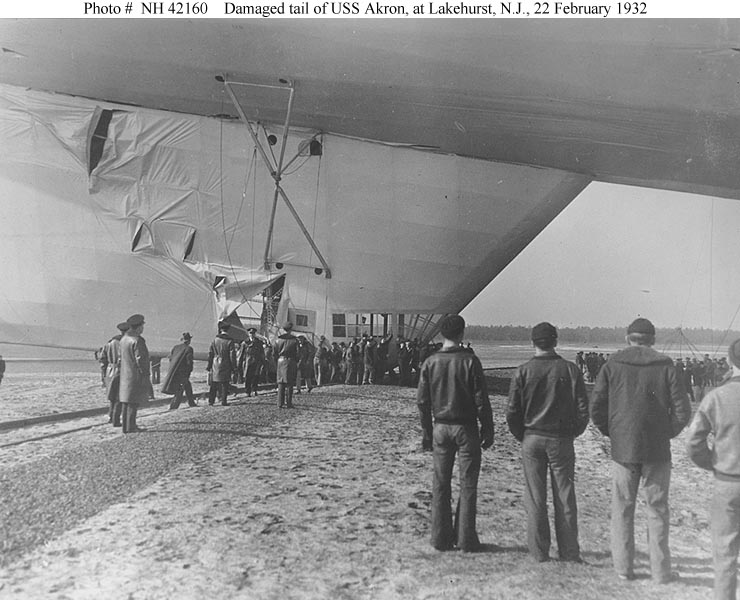

After just four months of service the Akron had an accident on February 22, 1932 when being taken out of its hanger. Its tail slipped its moorings and struck the ground, badly damaging the lower tail fin and some of the handling fittings on the mainframe. It was two months before the Akron was operational again.

But the following month after doing a three-day coast to coast flight to San Diego, California, tragedy struck.

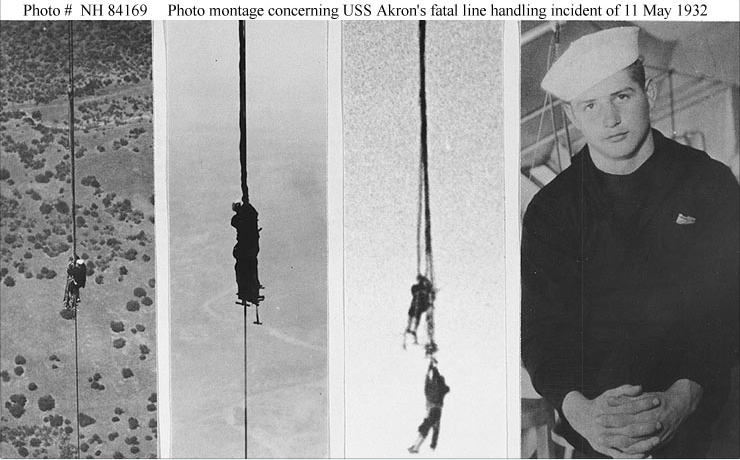

While attempting to land at the naval base at Camp Kearny, the Akron became uncontrollable and threatened to crash into the ground nose first. So to avoid a disaster the mooring cable was cut. Unfortunately, the seamen manning the landing lines were inexperienced in airship docking procedures.

With the mooring cable cut, the Akron soared rapidly upwards. In the panic and confusion, four of the ground crew did not let go of their landing lines and soared upward with the airship.

One of them quickly realized his mistake and let go when he was about 15 feet off the ground, breaking his arm as he fell to earth.

The others continue to cling to their lines as the Akron rapidly gained attitude. Unfortunately two of three seamen ended up losing their grip and fell to their death, while the third one managed to wrap the rope around himself and was hauled up into the airship about an hour later.

Then the Akron had yet another accident six months later, but thankfully this time it was minor. On August 22, 1932 while coming out of its hangar at Lakehurst, the Akron clipped a beam and slightly damaged its rear fins and some of its main frame.

After that, the Akron‘s run of bad luck seemed to be finally over. It successfully took part in military war games and training exercises, and even undertook visits to Panama and Cuba.

Then on the evening of April 3, 1933, the Akron was tasked with assisting in the calibration of radio direction finder stations in New England.

Onboard was the normal crew as well as Rear Admiral William Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. Also onboard were several other important military officers and the vice-president of the Mack Trucks corporation, who was a strong believer in airships’ potential for civilian uses.

The Akron soon encountered bad weather that continued throughout the evening with powerful gusts of winds. Just after midnight, the bad weather intensified into a full-blown thunderstorm.

Violent winds battered the Akron and despite the crew’s best efforts, the ship started to lose height. Its nose tilted upwards and the tail end of the airship crashed into the sea and was torn off, causing the rest of the Akron to collapse into the stormy Atlantic.

Rescue ships were quickly on the scene, but sadly of the seventy-six people onboard, only three survived. None of the three was the visiting dignitaries. Most had died of exposure or drowning in the turbulent and freezing cold sea. Incredibly, the Akron had not been equipped with life jackets.

Even further tragedy struck that night when the J-3, a small non-rigid airship sent to join in the search for Akron‘s survivors, also crashed into the sea killing two of its seven crew members.

The loss of the USS Akron was the biggest fatality in any airship crash at that point and shook the military’s faith in airships.

However, its sister ship the USS Macon, which had been commissioned just eleven weeks after the Akron disaster, seemed to fare much better. Over the next eighteen months of uneventful good service it completed fifty flights.

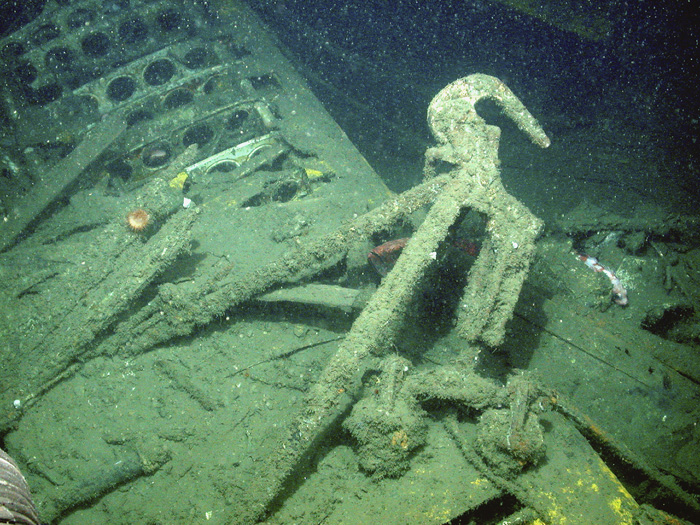

But then on February 12, 1935 the Macon encountered a storm off the coast of California. It was damaged by high winds, causing structural failure that was compounded by some earlier damage in the year that had not been fully repaired.

The Macon slowly descended and made a controlled forced landing into the sea.

Due to better weather conditions and the fact that the Macon had been equipped with life jackets after the Akron disaster, the loss of life was minimal in comparison, with only two fatalities.

For the US this was the beginning of the end of their interest in airships. With the German Hindenburg disaster two years later, the international community lost interest too.

Thus ended the golden age of the airship.