For countless centuries, China has suffered protracted periods of invasion and counter-invasion, insurrection, conquest, and war. Many of the deadliest of these wars occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries.

One conflict in particular stands out for its exceptionally enormous death toll which has earned it the ignominious honor of being the deadliest civil war in human history: the Taiping Rebellion.

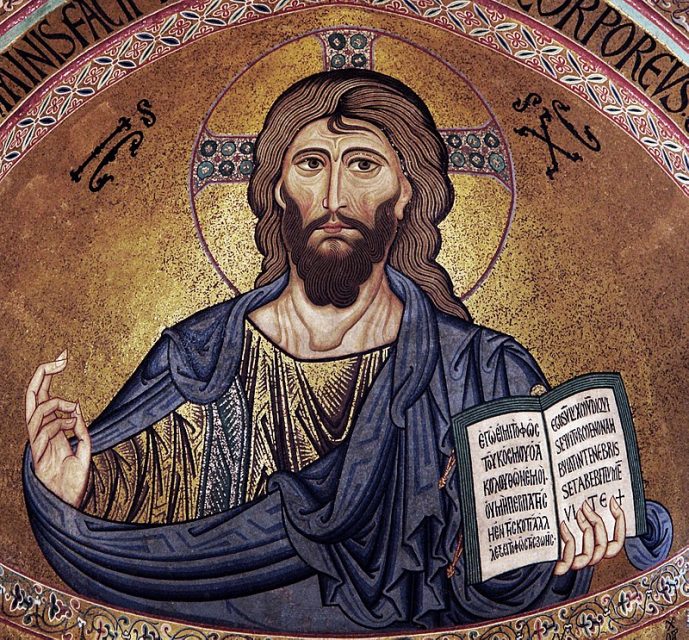

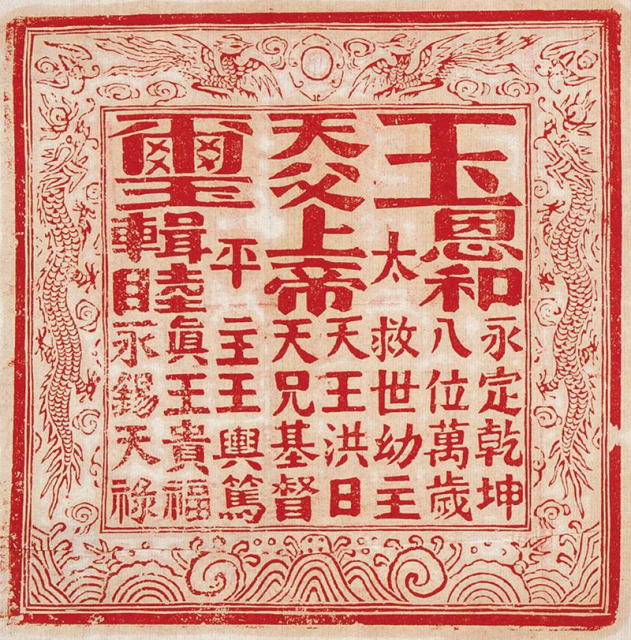

This conflict was fought between the armies of the Qing Dynasty and the forces of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. At the head of the latter was a former peasant named Hong Xiuquan, who believed himself to be a blood brother of Jesus Christ.

The Taiping Rebellion lasted from 1851 to 1864. At the end of this enormous civil war, 20 million people had lost their lives, a record that would go unequaled until the Second World War.

Hong Xiuquan (birth name Hong Huoxiu) was born in Fuyuan Springs in Guangdong in 1813. From an early age, he displayed remarkable intelligence. His family recognized this and invested their meager resources into getting him a good education.

While he was academically gifted, Hong was not able to pass the strict imperial examinations required to enter the upper echelons of the civil service. He tried and failed three times to pass these tests. After his third failure, he had a nervous breakdown.

While in this delirious state, he had a dream in which he visited heaven, where he discovered that he was part of a celestial family, different from his family on earth.

The head of this family, an old man with a long beard (whom he later believed was the Christian God) handed him a golden sword and instructed him to cleanse the earth of those who were worshipping demons. The old man also instructed him to change his first name to Xiuquan.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tYasXo4YOPs

Hong recovered from his breakdown and became a teacher, but the vision of God and heaven he believed he had witnessed stayed with him. He tried to pass the imperial exams in 1843 but failed to do so once again.

A few years earlier, he had been given a few Christian pamphlets by a missionary. After this fourth failure, he went back to the pamphlets and re-examined them. It was at this point that he decided that the celestial family he had been part of in his dream had been that of the Christian God.

He became convinced that Jesus Christ was quite literally his older brother and that he, Hong Xiuquan, was therefore the Son of God.

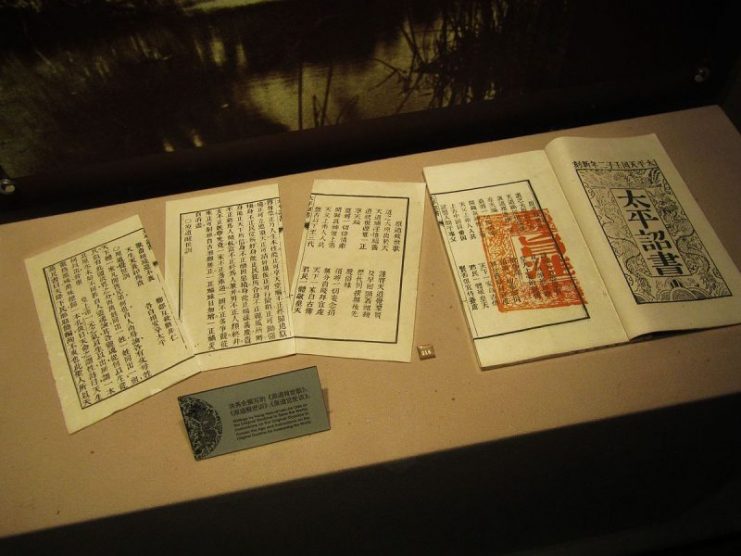

He had two large swords forged, which he called “demon slaying swords.” He began destroying Buddhist and Confucian books and statues in his village and preaching his message (which was not Christian doctrine but rather a blend of Christianity, Chinese folk religion, Shang theology, and his own beliefs) to his community.

While converts to this new religion did not initially flock to it en-masse, within a few years Hong had amassed enough followers to give his movement a name: he called it the God Worshipping Society.

The principles Hong was preaching quickly started to become more militaristic and openly rebellious against the ruling Qing Dynasty.

It is important, at this point, to note that huge numbers of disaffected Chinese peasants were in a position that would have made them receptive to the kind of insurrectionary teachings that the God Worshipping Society was spreading.

During the first half of the 19th-century, China – especially southern China, where Hong was based – had been hit by a crushing series of natural disasters: floods, droughts, and famine.

Corruption among government officials was rife, and the Qing Dynasty was seen as aloof and uncaring about the problems faced by the peasants. The emperor’s government had also done little to assist the lower classes in the wake of these troubles.

Furthermore, the nation was in the grip of an opium epidemic and had recently suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the British in the First Opium War (1839 – 1842).

There were also ethnic tensions Hong was able to exploit. He was part of the Hakka minority, who, along with the Han population, had long resented the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty.

Hong’s new religion preached, along with its spiritual ideas, a kind of primitive communism in which everyone could own a piece of land. Such teachings held great appeal to landless peasants.

By 1850, Hong’s God Worshipping Society had grown to almost 30,000 followers. He had declared himself the Taiping King, ruler of the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. He told his followers that the demons God had instructed him to slay were the members of the Qing Dynasty.

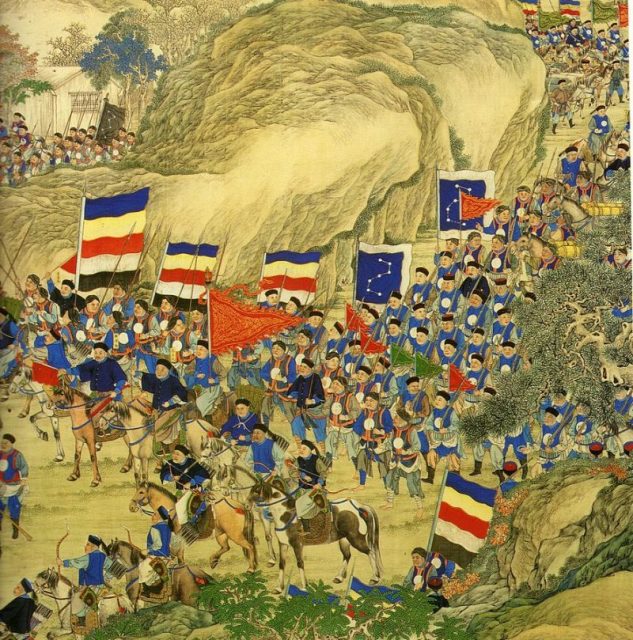

He began organizing his followers into a military hierarchy as well as stockpiling weapons and gunpowder.

Alarmed at what was happening in the south-west of China, the ruling Qing Dynasty demanded that Hong disband his cult. Predictably, he refused, so the Qing authorities sent an army to crush him.

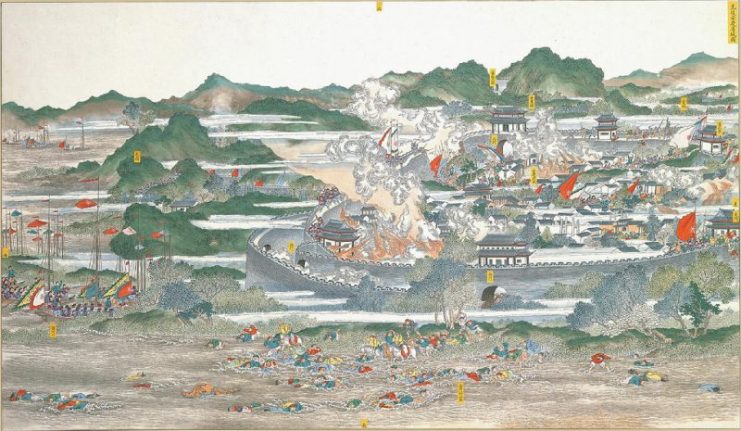

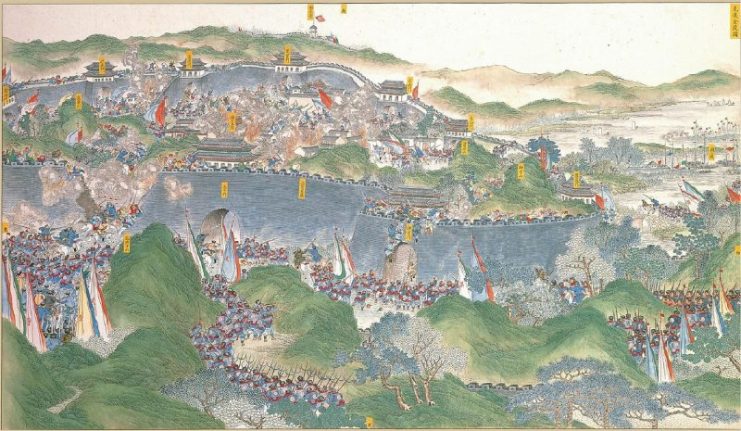

Hong’s followers, however, were stronger and better-organized than the government forces had anticipated. In February 1851, the Taiping army routed and wiped out a force of 10,000 Qing men. The Taiping Rebellion had officially begun.

Even after this initial defeat, the Qing Dynasty did not anticipate that it would take too long to put down Hong’s rebellion. Their army outnumbered Hong’s by ten to one. They also possessed better weapons and far more money.

What they did not realize, however, was how receptive Chinese peasants would be to Hong’s message. Hong’s movement continued to swell, gaining terrifying momentum.

On the 25th of September 1851, the town of Yongan fell to the Taiping forces. The occupiers were later driven out by the Qing army in a battle in which they lost 20% of their fighting men.

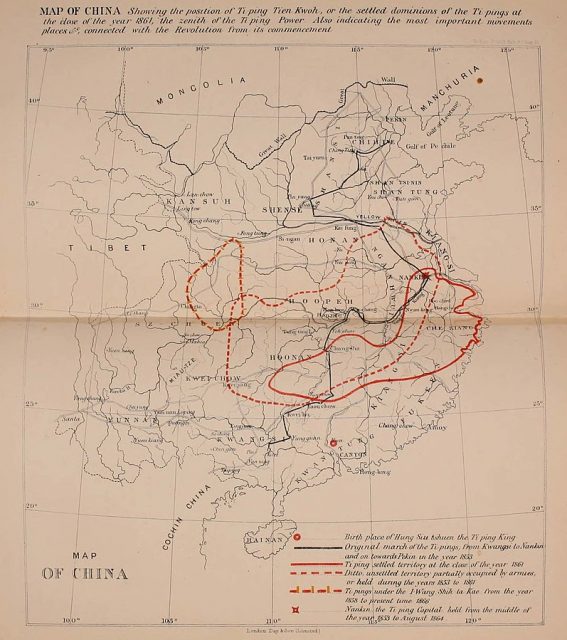

However, the Taiping forces regrouped and reorganized, while Hong continued preaching and recruiting followers. In March 1853, they assaulted and took the city of Nanjing, which was where Hong established the capital of his kingdom.

By this time, Hong had amassed an astonishing following of almost two million people and had an army of one million soldiers at his command.

At Nanjing, he established a new society in which men were equal to women. Polygamy – a long-established tradition in China – was outlawed, as was slavery, foot-binding, idol worship, and a host of other long-standing Chinese traditions.

Despite preaching against licentiousness and sexual promiscuity, though, Hong had around 100 concubines. He also banned the smoking of opium.

He aimed to end private land ownership and place serious restrictions on both local and international trade. Through a series of conquests by the ever-swelling ranks of his army, Hong eventually managed to conquer almost a third of China.

These conquests saw a staggering degree of violence, both on the part of the Taiping forces and the Qing army. Often, the entire population of a town or city was put to the sword. Torture was widespread, and brutal executions of captured enemies were common, as were rapes and beheadings of civilians.

Hong also began to grow paranoid about his own followers plotting against him. He had those he suspected of possible treachery – and their families – executed.

Alarmed at the possibility of the loss of extremely profitable trade revenues from China, the British and French eventually came to the aid of the Qing Dynasty. The tide of the civil war began to turn. In 1861, when Taiping forces tried but failed to take Shanghai, it was obvious that their momentum was lost.

Gradually, Taiping strongholds fell to Qing forces which were now assisted by British troops and American mercenaries. Defeat after defeat followed for the Taiping forces, which were also weakened by infighting and corruption.

In the spring of 1864, Qing forces besieged the Taiping capital, Nanjing. Running low on food, Hong and his remaining followers were reduced to eating weeds for sustenance – which, it is theorized, is what killed him. When the Qing forces finally took the city, Hong’s decomposing corpse was discovered in his palace.

The final Taiping loyalists were crushed in battle later that year, and by the end of 1864, the Taiping Rebellion was finally over.

Hong’s body, after an initial burial, was exhumed and then cremated. His ashes were blasted out of a cannon so that he would have no final resting place – an eternal punishment for his uprising.

By this time, an estimated 20 million (some say as many as 30 million) people had been killed. This figure makes the Taiping Rebellion the bloodiest civil war in human history and second only to WWII as the deadliest conflict ever fought.