“the Germans were banging on the doors with the butts of their rifles…. And they would always yell – it was very frightening.”

When it comes to the exploits of World War II, there are plenty of heroes for us to remember. But a group of three Dutch women isn’t necessarily what springs to mind.

Freddie Oversteegen was in the news last year when she passed away. She was the last remaining member of the trio. Her sister, Truus, had died two years before, and their friend Hannie Schaft never made it to her 25th birthday as she was executed in Bloemendaal in the Netherlands.

Truus Menger-Oversteegen was born on August 29, 1923. Her little sister, Freddie, came along on September 6, 1925. The two of them lived with their parents on a barge in Haarlem.

Although their parents divorced, in an interview Freddie gave in 2016 she spoke about how there was no acrimony between her parents. She added that her father “sang a French farewell song from the bow of the ship.”

After that, the mother and two daughters moved into a flat. They were so poor that their mother had to make straw mattresses for them to sleep on. Yet their poverty didn’t stop their generosity to others.

The family had hidden Lithuanian refugees on their boat. When they moved into the flat, they sheltered a Jewish couple. From these refugees, Freddie and Truus learned what was happening in the war.

However, they also witnessed events first hand. Speaking later in life, Freddie said that after the traditional two-minute silences on days of remembrance to commemorate the fallen, she thinks of how people were taken from their homes and how “the Germans were banging on the doors with the butts of their rifles…. And they would always yell – it was very frightening.”

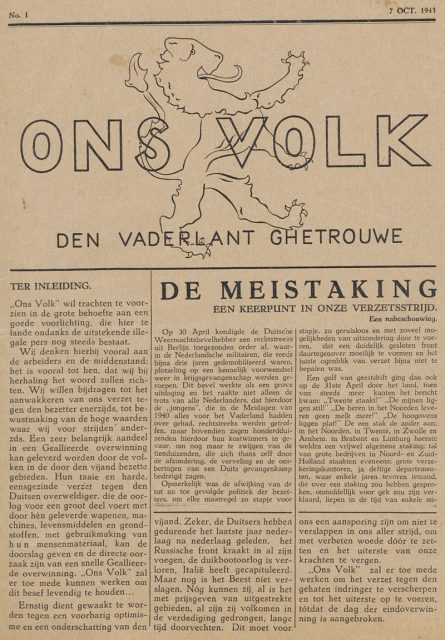

Their mother was a communist with strong principles. The two sisters went with her when she handed out anti-Nazi leaflets. They also pasted warnings over posters that encouraged Dutchmen to go to Germany, such as: “For every Dutch man working in Germany, a German man will go to the front!”

When Truus was 16 and Freddie was 14, they were invited to join the Raad van Verzet (the Council of Resistance). As Freddie put it: “A man wearing a hat came to the door and asked my mother if he could ask us.” Their mother agreed, and the two girls joined up.

Freddie described how she and Truus thought they were joining some kind of secret army. In secluded locations, they were taught how to shoot and to march as a part of a small resistance cell in which they were the only girls.

The two girls developed a novel way of executing Nazis: a drive-by shooting on a bicycle. Hannie Menger, Truus’s daughter, recalled being told how her mother would steer the bicycle while Freddie sat at the back and shot at Nazis and Dutch collaborators. They generally went unnoticed as they were just two pretty girls riding on a bicycle.

They also had another way of carrying out assassinations. One or both of them would flirt with a Nazi or a Dutch collaborator, then ask them if they wanted to go for a walk in some nearby woods. The men would rarely turn down such an offer, but they were walking to their deaths as other resistance members waited in the woods, ready to shoot them.

This successful modus operandi had its mental effects on the girls, though. In 2016, Truus revealed in an interview of her own that “It was tragic and very difficult and we cried about it afterwards.” Far from relishing their femme fatale roles, Truus described how it “[poisoned] the beautiful things in life.”

It was while they were members of the Council of Resistance that they were to meet Hannie Schaft. The three of them became inseparable.

Hannie was born and raised in Haarlem as well, although her birth name was Jannetje Johanna Schaft. Her father was attached to the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, and she often talked about social justice and politics with her parents. They encouraged her to become a human rights lawyer.

While Hannie was studying law at the University of Amsterdam she met two people who would influence her significantly: Philine Polak and Sonja Frenk, who were both Jews. Through her friendship with them, Hannie came to understand and respect the Jewish faith.

When the Nazis occupied the Netherlands, all the students were required to sign a declaration of allegiance. Hannie refused and in return was denied permission to continue her studies. She moved back in with her parents, and that’s when she became involved with the Dutch resistance.

Like the Oversteegens, Hannie started out with small acts of resistance. She began by stealing both ID cards and ration cards which she would then pass onto Jewish residents. From there, she began distributing pamphlets and stealing weapons.

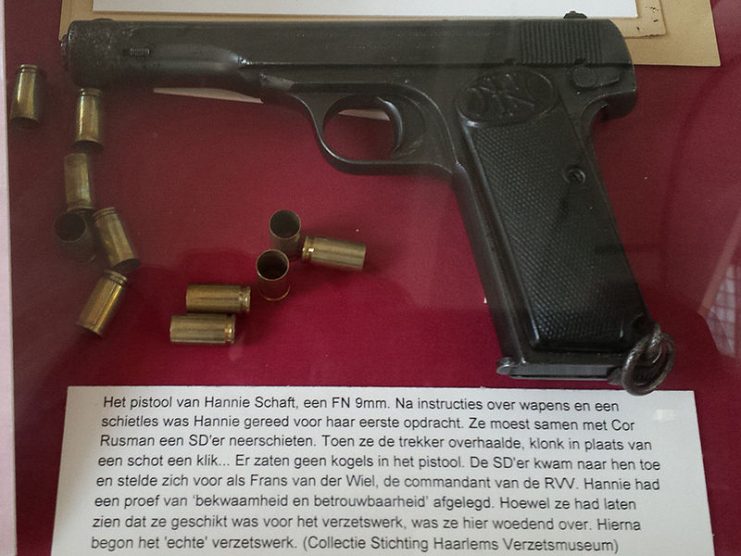

In 1943, she officially joined the Council of Resistance, and it was there that she was given the name “Hannie.” She moved from stealing weapons to learning how to use them, and that’s when she came into contact with the Oversteegen sisters.

Together, they would assassinate given targets, assist Jewish people in fleeing from the Nazis, and even sabotage railways. When sent to bring down Nazi collaborators, they would use their charms to lure the men into a trap. They even achieved the audacious task of raising a communist flag at the headquarters of the National Socialist Movement.

All three girls had received strong, moral upbringings. Freddie revealed how their mother had given them one piece of advice upon joining the resistance: “Always stay human.”

On one occasion, the three girls refused an order to kidnap the children of a Nazi official. They felt sure the children would be hurt or killed, even though the plan was to exchange them for Dutch prisoners. Hannie is reported as saying: “We are no Hitlerites. Resistance fighters don’t murder children.”

During one of her assassination missions, Hannie was briefly glimpsed by her enemies and, although they had no name, the Nazis listed her as “the woman with the red hair” and placed her on their most wanted list.

The Nazis finally obtained Hannie’s name from Jan Bonekamp, a man she had been paired with before he was shot and captured. Bonekamp revealed Hannie’s name under torture. The Nazis arrested her parents and sent them to a concentration camp, which forced Hannie to go into hiding and stop her resistance activities.

However, once her parents were released Hannie dyed her hair black and went back to resisting the Nazis.

On March 21, 1945, Hannie was arrested. She had been caught at a checkpoint carrying the socialist newspaper de Waarheid and a weapon.

The young woman was subjected to torture and solitary confinement, but it wasn’t her words that gave her away – it was the red roots of her hair that started to show above the black dye.

Although there was an agreement in place at the end of the war to stop executions of resistance fighters, the Nazis deemed Hannie too notorious to be left alive.

Three weeks before the war officially ended, she was taken to the dunes of Bloemendaal by two men. One man tried to execute her with a single shot, but he only wounded her. Defiant to the last, Hannie said to him, “I shoot better than you.” She was then shot and killed by the second man.

Hannie might not have seen the end of the war, but she was not forgotten – at least initially. The bodies of 421 men and one woman (Hannie) were uncovered in the Bloemendaal dunes. On November 27, 1945, Hannie was reburied and received a state funeral.

However, as the Cold War began, communism fell out of favor, and the Dutch government wanted to forget its communist past – which included Hannie Schaft. In later life, Freddie Oversteegen confided many things to the filmmaker Manon Hoornstra who said that “Hannie was [Freddie’s] soulmate friend…. She always took red roses to her grave.” Hannie continued to live on in the memories of her two best friends.

Truus married a fellow resistance fighter and was perfectly open about her experiences during the war. She became a painter and sculptor, often using her war experiences to inspire her art. She also gave many public speeches about war, anti-Semitism, and other related matters.

However, Freddie found it too difficult to talk about what she had experienced. She also felt side-lined by her sister’s fame and began to feel increasingly alienated by her country that wished to bury the brave deeds of herself, her sister, and her friend.

In 1981, a film was made about Hannie Schaft entitled The Girl With The Red Hair. This movie helped to bring the actions of the three girls back into the spotlight and led to the Oversteegen sisters receiving the Mobilization War Cross in a move that the Dutch prime minister called “an act of historical justice.”

The two sisters remained close until Truus’s death in 2016. Freddie survived another two years, dying the day before her 93rd birthday.

These three women might be gone, but their legacies live on. The National Hannie Schaft Foundation was started by the Oversteegen sisters in 1996.

In 1951, commemoration at Hannie’s grave had been forbidden, and commemorators were held back by police and the military, which included four tanks. However, in the early 1990s, the efforts of the Foundation ensured that commemorations could take place once again, on the last Sunday of each November.

To this day, they are not forgotten.