Rommel led this attack from the front. He and his men took the town in an hour, personally leading the capture of two houses which had set up an ambush.

Erwin Rommel, the famed “Desert Fox” of World War II, fought on a completely different front in WWI: in the foothills of the Italian Alps, and at the great battles in the Isonzo River Valley north of the Adriatic port of Trieste in Italy. He also fought in France in some of the same areas that would see his “Ghost Division” blitz past French defenses in WWII.

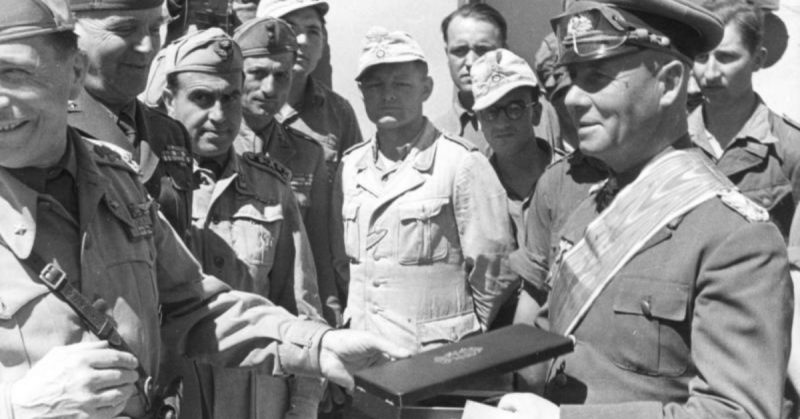

At the age of 26, Rommel was awarded Germany’s highest battlefield honor: the Pour le Merite’, or the “Blue Max” as it was known to the soldiers and public.

Rommel was almost fully prepared for WWII by the end of WWI. Initially, he commanded a reserve artillery company, then moved to command troops in the infantry. At the end of the war and between the wars, he familiarized himself with and innovated mobile armored warfare.

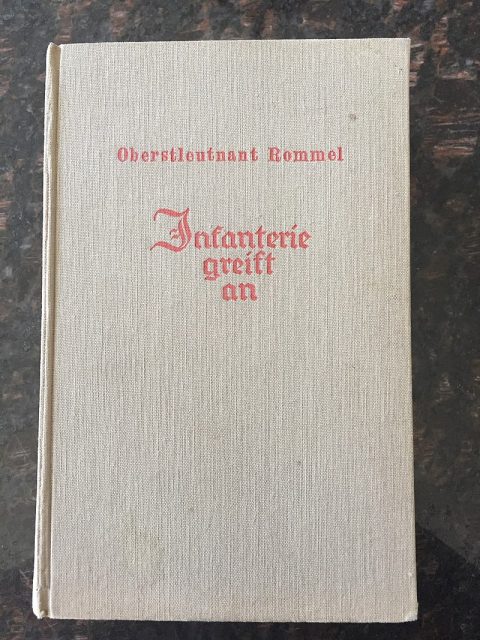

After WWI, Rommel wrote a series of articles and papers for the German general staff, and one of the most famous and influential military books of the 20th century: Infanterie greift an, or “Infantry Attacks”. This is the book that George C. Scott as Patton refers to in the movie: “Rommel, you magnificent bastard, I read your book!”

What exactly did Rommel do in WWI, and how did he win the Blue Max?

Leading From the Front

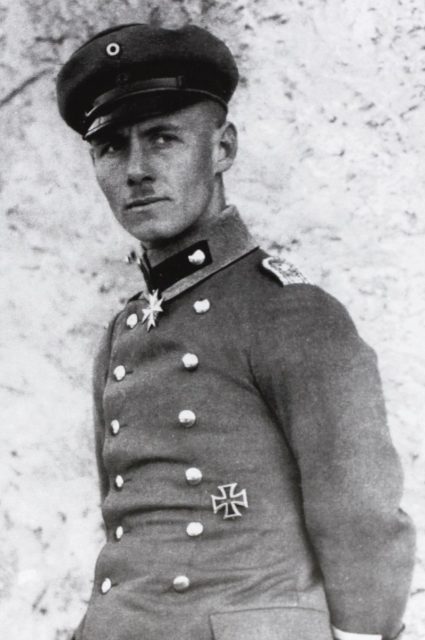

At the start of WWI, Rommel had been in the army for four years. As a youth, Rommel wanted one thing – to be an officer. In pre-WWI Germany, serving in the armed forces, especially as an officer, was a highly coveted and respected career. In small towns and villages, active and retired officers were often consulted on the most important matters, and everywhere, civilians deferred to military men.

Rommel went to officer cadet school in Danzig and was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1912. Like most officers at the time, both in Germany and elsewhere, he was posted to a unit from his home region of Württemberg, the 124th Infantry Regiment. He did a stint with the Württemberg artillery just before the war and returned to the infantry when war broke out.

If you are familiar with the stories of great military leaders, you’ll know that many of them won the respect of their men because, at least at one stage of their careers, they led from the front. In the case of Rommel, this was true through WWI and even into the Germans’ 1940 French campaign and the campaigns in Africa.

For Rommel, this began just south of the Ardennes, near the small village of Bleid in Belgium. Rommel’s initial task was to scout out the buildings and hedgerows on the edge of town for any sign of the French.

Surprise sometimes outweighs numbers, but it takes a bold man to order three other men to open fire on fifteen, which is just what Rommel did when he found a group of Frenchmen having breakfast. They killed five of the enemy and routed the others. When the French got their act together, they returned fire, and Rommel returned to his battalion, which then attacked the French in force.

Rommel led this attack from the front. He and his men took the town in an hour, personally leading the capture of two houses which had set up an ambush. The entire attack was bold and made with split-second decision making by Rommel. Sound familiar?

Two Iron Crosses

Shortly after the attack on Bleid, Rommel was seriously wounded in the leg and hospitalized for three months. For the action in which he was wounded, he received the Iron Cross 2nd Class. When he returned to duty, the initial days of maneuver were over and the war had begun to settle down into the horror of trench warfare.

In January 1915, Rommel led a platoon through a section of the Argonne Forest, looking to penetrate French lines and test their defenses. His men found a break in the barbed wire and the Germans infiltrated the French position, forcing out their enemy.

Not long after this, Rommel realized they had made a mistake – the position was open to attack from the rear towards the French lines and the dirt was too hard to dig trenches, especially in a short time, so they occupied a nearby farmhouse.

As is the case with many a defensive stand, the Germans held off many French counter-attacks and steady fire, but the Germans were running out of ammunition and would soon be forced to retreat or surrender. Of course, there was another alternative: do the unexpected and charge the enemy with fixed bayonets, shock them into retreating, then retreating back to German lines.

Guess which route Rommel chose? Correct! The charge scattered the enemy long enough for him and his men to return home. Rommel was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class for this action.

The Italian Front

Many people believe that the WWI “storm-trooper” concept came about in 1918 with the German summer offensive. This is both right and wrong. In 1918, the Germans used specially trained assault troops in large numbers for the first time as complete units, but the training, equipment, and concepts had been experimented with by almost all sides in the war for some time by 1918.

One of the groups that was a kind of forerunner of the storm-troopers of 1918 was the men of the Royal Württemberg Mountain Battalion, who were fighting on the Italian Front along with their Austro-Hungarian allies. Rommel transferred to this unit in the fall of 1917.

Like the later groups, and like many of today’s infantry and special forces, these mountain troops were trained in highly developed small group tactics, were armed to the teeth, and realized the value of overwhelming and surprising violence in their attacks. Rommel’s ideas of small unit actions and the men of the mountain battalion meshed perfectly, and Rommel’s greatest attack of the war was to influence what was to come.

The Italian Front, much overlooked in the history books, was a hell of its own. Fought in either tightly packed, muddy and flood-prone river valleys, or high in the Alps where the weather was inclement much of the year, the Italian Front was just as brutal as the fighting in France and Belgium. To this day, explorers and mountain climbers find the frozen remains of the men of WWI high above the scenic valleys below.

Between October 25-27, 1917, Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant) Rommel led an assault for the history books. The objective for the attack was to take Italian positions near the summit of Mount Matajur on the border of today’s Italy and Slovenia. Two nearby peaks were also to be taken.

By mountaineering standards, Matajur is barely a mountain, but at over 5,000 feet above the valley below it was hardly a cakewalk, especially for anyone facing deeply entrenched troops. The attack was a small part of the giant Battle of Caporetto, one of the most costly battles of the war in Italy.

A Bold Trap

On the 25th, Rommel led his 150 men up the ridge of Mt. Kolovrat and found a large group of Italians hunkered down in their trenches, avoiding detection by a Bavarian unit nearby. Rommel and his men hid until they found a hidden way through the Italians’ positions and then attacked them from the rear.

Within minutes, they had captured hundreds of Italian troops, but the Italians mounted a strong counter-attack within minutes, pouring fire down upon the Germans from above.

Staying where he was would mean that eventually the Italians would kill or wound all of his men and they could charge downhill into a relatively weak position. Can you guess what Rommel did? You’re right. Leaving his 1st and 2nd companies along with his machine-gun platoon behind to provide covering fire, Rommel led his 3rd Company into a position near the Italians that was invisible to the latter because of the terrain.

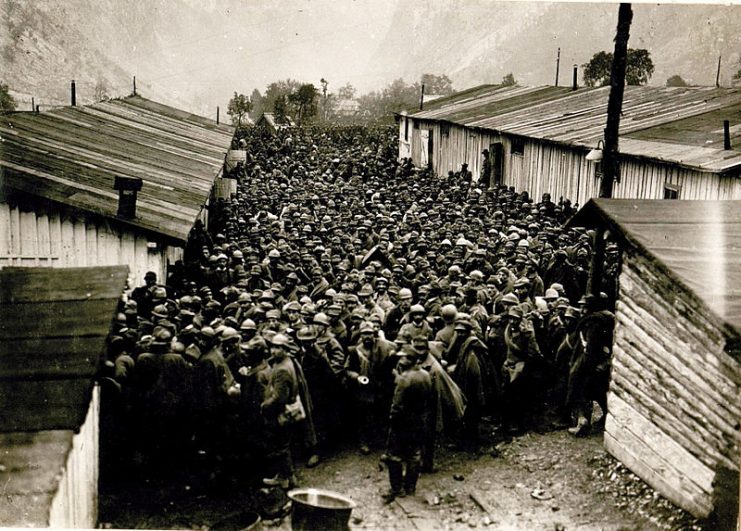

The Italians charged into the 2nd Company, but midway through their advance, Rommel and the men of the 3rd rose from their position and attacked them from behind. At that moment of confusion, the men of the 2nd rose from their positions and charged the Italians, who were now being attacked from both sides. Soon they surrendered: 12 officers and 500 men. Rommel’s 150 men had taken 1,500 POWs so far.

Leaving a small force behind to watch the POW’s, Rommel took the rest of his men down a supply road on the Italian side of the ridge, finding a village full of supplies. In a ferocious assault, Rommel’s men pushed into the town, killed some and took even more prisoners after ten minutes of hard fighting.

The Italians in the village later told Rommel that they thought they were being attacked by a much larger force. 2,000 prisoners were taken.

“Shed Sweat, Not Blood”

Rommel’s goal of taking Mount Matajur was still unfinished, however. During the night, he moved his men into position, taking 1,600 POWs along under threat of death. Foreshadowing events in WWII, the Italians on the path to the peak surrendered without firing a shot. 1,500 more POWs.

At that point, runners delivered orders for Rommel to return to German lines to resupply and reorganize. He ignored these orders, knowing that if he followed them, all of the gains his men had made would be for nothing.

Rommel was determined to take his objective: the peak of Mount Matajur, which dominated and observed the small valley below. With Matajur in German hands, they could see for miles and determine Italian moves almost before they made them.

Rommel ordered his machine guns to keep up a steady fire on the peak as his incredibly fit men ran, jumped and leapfrogged over obstacles on their way up the mountainside. On the peak, the Italian commander surrendered without firing a shot – all of his support positions and his supplies had already been taken by Rommel’s men.

Read another story from us: Rommel Defeats the Free French: Battle of Bir Hakeim

In over two days of almost continuous combat and movement, Rommel and his men had taken 18 miles of Italian territory, climbed two miles of mountains, captured 9,000 men, killed hundreds of others, and captured a supply depot and their main objective with a loss of six dead and 30 wounded.

One of Rommel’s more famous quotes was “Shed sweat, not blood.” This is how Lieutenant Rommel won his “Blue Max,” and it was the beginning of his road to fame.