Submarines did not become common in naval forces around the world until the 20th century. But one did exist in 1860s America during the Civil War–the USS Alligator.

It wasn’t until 1861 that the US Navy locked onto the idea of a boat that could travel underwater. It had been considered as far back as the Revolutionary War when the USS Turtle was invented, but it took until the mid-19th century for efforts to truly begin.

The Union Navy was up against the CSS Virginia, a Confederate steamship that seemed essentially bulletproof. The Union couldn’t take it out of commission by mere firepower.

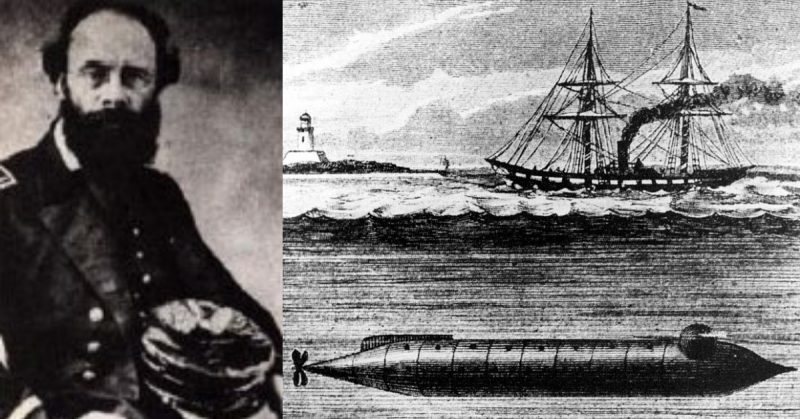

The Union Navy approached the marine engineering firm Neafie & Levy of Philadelphia, one of America’s iron shipbuilding firms, regarding the creation of a submarine. The company then brought in French engineer Brutus de Villeroi to get to work on the project.

Just 40 days later, the Union got the Alligator, so named because it was the same color as the amphibian creature. The project set the Navy back $14,000 (U.S.) – an enormous sum in those days.

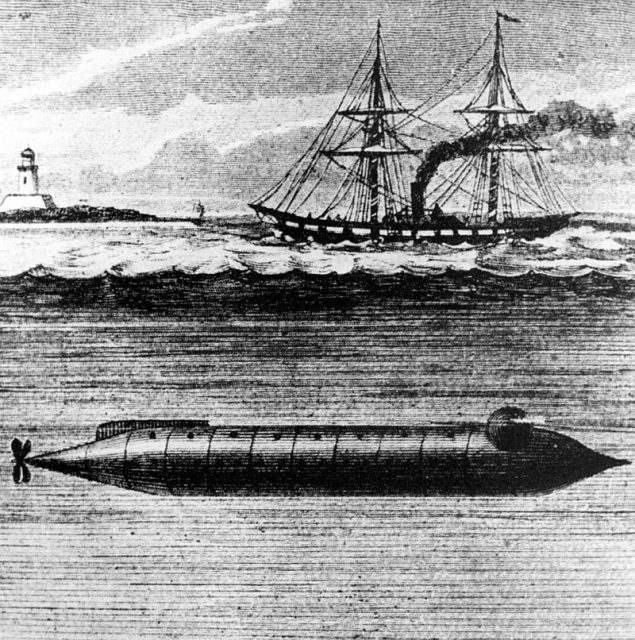

No pictures of it exist today, of course, but historians believe it was crudely built, at least by today’s standards. It was constructed entirely of iron, and had only small windows from which to see out. It is uncertain whether its crew was eight men or fourteen.

Some believe its length was just 30 feet, though others put that figure at 47 feet. It’s impossible to say because soon after the Alligator‘s first tests the submarine was lost in the Atlantic.

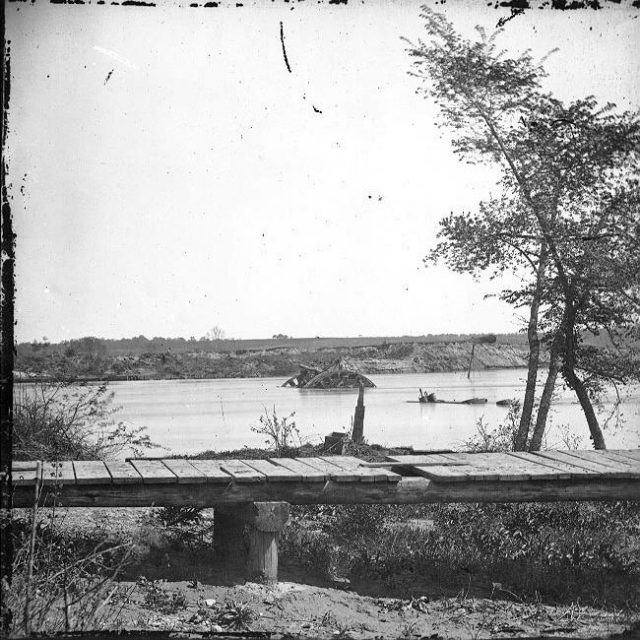

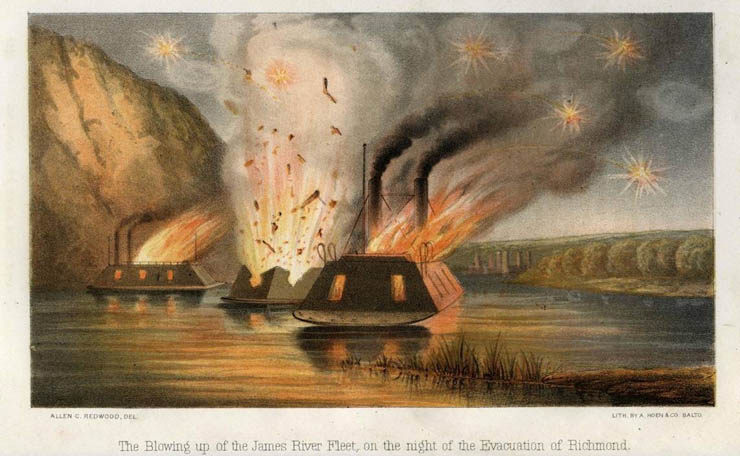

The project had been plagued by problems from the outset. The sub was sent for its first test to the James River in Virginia. Officials wanted it to take out a bridge on the Appotomax River. However, both rivers were too shallow for the sub to remain completely submerged.

The entire test was deemed a complete failure, and the Alligator was sent to the Washington Ship Yard for modifications.

During the time spent improving it, the Confederates built a replacement for their bulletproof boat, the CSS Virginia II, an even tougher adversary. The Navy brought in a new crew and new captain for the Alligator, Lieutenant Thomas O. Selfridge Jr., who was assured a promotion if he could just destroy the Virginia II.

But the sub’s next test, on the Potomac River, proved harrowing for all involved. The air system failed, and the little air they had was not breathable. The crew was forced to scramble to exit through a small hatch. This whole episode, too, was declared an unmitigated disaster.

Additionally, the sub lacked enough power to operate effectively. After this series of setbacks, new oars were attached and a hand-cranked propeller was added to increase its speed to seven knots.

Finally, the Navy deemed it ready to take on an actual battle.

It was ordered to help in the fight to win Charleston, South Carolina, and left harbor on March 31, 1862. On this venture, it was commanded by Samuel Eakins. The sub had to be towed to battle by the USS Sumpter.

But within 48 hours, the two boats ran into terrible weather off the coast, and the USS Alligator’s connection to the Sumpter was severed in the storm. Neither the sub nor its crew were ever seen or heard from again.

Modern attempts to locate the sub have proved fruitless. Even when the Office of Naval Research joined forces with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration in the mid-2000s, they had no luck.

Their searches focused on an area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” because of the number of vessels lost there. The teams used information gleaned from documents indicating where the sub may have sunk, but still–nothing.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Someday, perhaps, the USS Alligator will be found. For the moment at least, it lies undisturbed on the ocean floor.

Even though it never made a successful wartime voyage, it taught Navy personnel invaluable lessons about submarine building, and what it would take to create a viable submersible craft that sailors could use in generations to come.