More than a hundred years ago, Europe and America were convinced that serious and large-scale military conflicts were impossible. On January 1, 1901, in the Chicago Tribune, there was a record that “The twentieth century will be the century of humanity and brotherhood of all people.”

However, the “Age of Humanity” soon turned into an unprecedented slaughter when the First World War started on July 28, 1914.

World War I, apart from death and destruction, brought many technological, scientific, and social innovations. Chemical weapons, machine guns, tanks, the development of aviation, and the use of submarines appeared during the First World War.

These all led to very serious injuries. By the end of the war, there were twice as many wounded as there were dead.

Need is the mother of invention. The new needs of military medicine stoked the urgent requirement for innovation, and many of those advancements are still relevant and used in our time.

One of the most important innovations was the system for sorting wounded soldiers. Also during the First World War, a mobile X-ray machine was used to detect bullets and shrapnel. Severe facial injuries, including those caused by martial gases, contributed to the development of plastic surgery.

Stewart Emmens curator of the exhibition Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care at the Museum of Science in London, argued that “The scale of the injuries had no precedent, as well as their severity.”

World War I contributed to the development and widespread use of blood transfusion and storage. This made it possible to save the lives of many soldiers, and this technology was introduced into everyday life. However, the history of blood transfusion originates from antiquity, when people tried to be treated with the blood of animals.

In the writings of the ancient Greek poet Homer, it is said that Odysseus, in order to return speech and consciousness to the shadows of the underworld, gave them blood to drink.

Hippocrates recommended that patients with mental disorders drink the blood of healthy people. In the writings of Pliny the Younger, there are indications of such treatment with blood in which it was reported that old people and people with epilepsy drank the blood of dying gladiators.

In ancient times, it was believed that blood is a miraculous liquid and its use could prolong human life for many years. According to unconfirmed testimony, in the fifteenth century, medicine was prepared from the blood of three boys to save the life of Pope Innocent VIII. However, this “elixir of life” did not help the dying man.

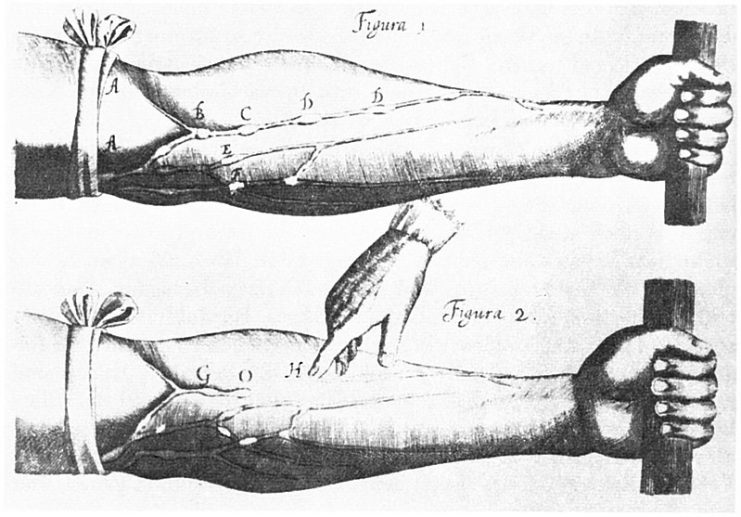

On April 16, 1618, William Harvey, a well-known English scientist and doctor, gave a public lecture in London for the first time about his experiments and thoughts about the circulatory system of humans and animals.

Ten years later, Harvey published the book Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Latin for “An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Living Beings”).

Consequently, he opened up opportunities for developing a method of blood transfusion. In 1666, the first successful experiments were performed on blood transfusion from one dog to another.

In the history of mankind, the development of donation methods has been accompanied by numerous ups and downs, ranging from the deification of this method to the prohibition of its use.

Before the outbreak of World War I, blood transfusions were rarely performed. This was a dangerous procedure, in part because the blood test for infections and compatibility was not carried out.

The first blood transfusions were made directly from the donor to the recipient because there was no special way to store blood. But the ignorance about blood groups led to many soldiers dying due to the lack of a suitable Rh factor.

Professor Francis Peyton Rous of the Rockefeller Institute in New York was looking for a way to preserve fresh blood. To prevent blood coagulation, he added potassium citrate to it and dextrose as an energy source.

From 1916 to 1917, Major Lawrence Robertson from the Medical Corps of the Canadian Army, under field conditions, conducted a series of blood transfusions from patient to patient, but without checking their compatibility.

While this procedure sometimes led to the death of the soldiers, it nevertheless tripled the survival rate of wounded soldiers.

In 1917, during service in France with the US Army Medical Corps, Captain Oswald Robertson, an English-born medical scientist, demonstrated that blood could be stored for emergency use. He used sodium citrate to prevent its clotting and thus managed to store blood for up to 28 days in a special refrigerator.

Read another story from us: Recovery on Rails: Ambulance Trains of World War One

After that, during the First World War, the United Kingdom used a mobile blood transfusion station, in which blood was stored in closed containers. The first experience was extremely successful and allowed doctors to save the lives of many soldiers.

Oswald Robertson is considered the creator of the world’s first blood bank and its mobile version.

Blood transfusion can rightfully be considered one of the most important achievements of medicine during the First World War. This was the next step in the development of blood donation.