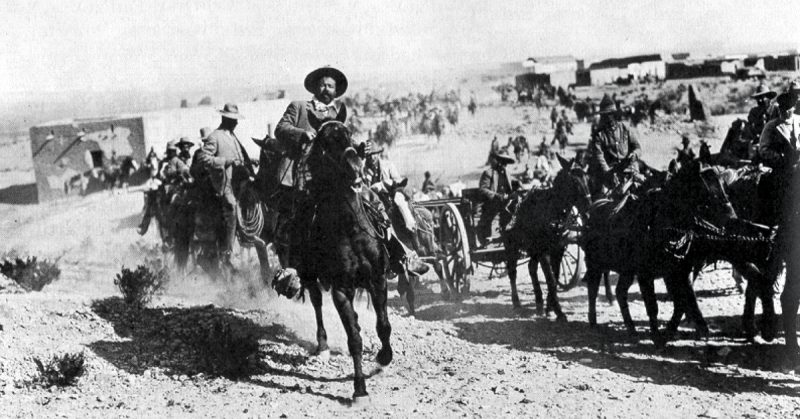

In the wee hours of 9th March 1916, the city of Columbus, New Mexico lurched to wakefulness as the grounds shuddered under the aggressive march of Villista forces. They rode and marched beyond the walls of the sleeping city, bearing guns and torches, fueled with rage and desire to plunder.

With eighteen dead and eight wounded, Columbus lay in ruins by the time the sky had peeled off the greyness of dawn, with thick smoke telling tales of the vindictive act of the revolutionist guerillas.

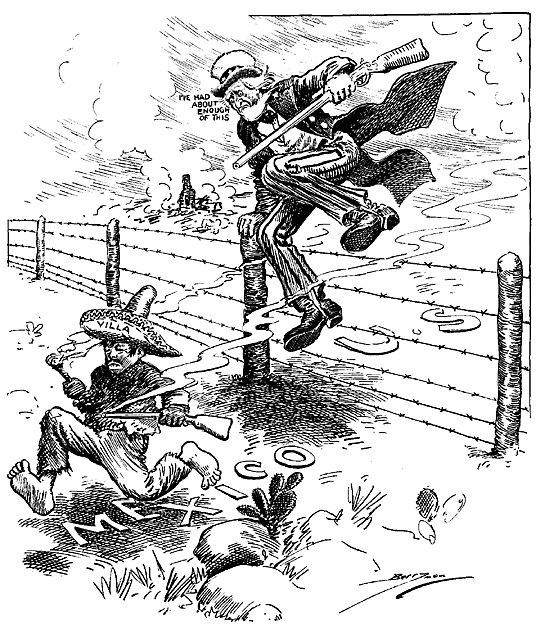

Despite inflicting even heavier losses on the raiders, America’s anger would not be satiated and it proceeded with an itching determination to punish the mastermind of the raid. The irony lays in the fact that just months before the U.S. had been supporting Villa’s efforts of rebellion in Mexico.

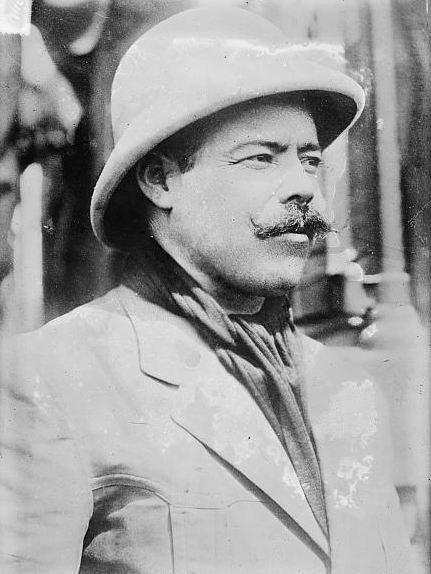

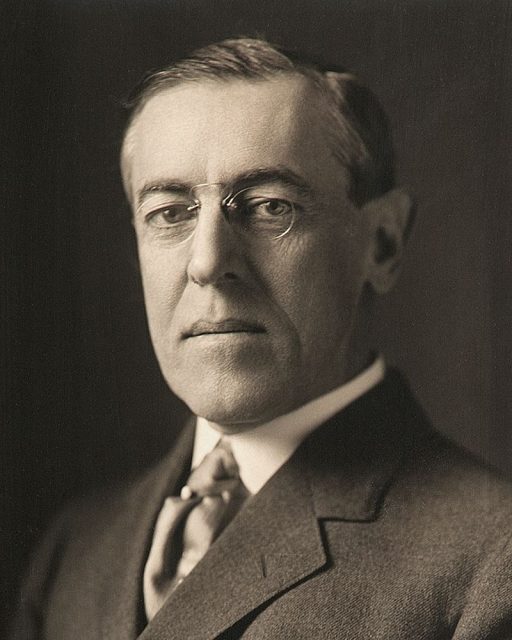

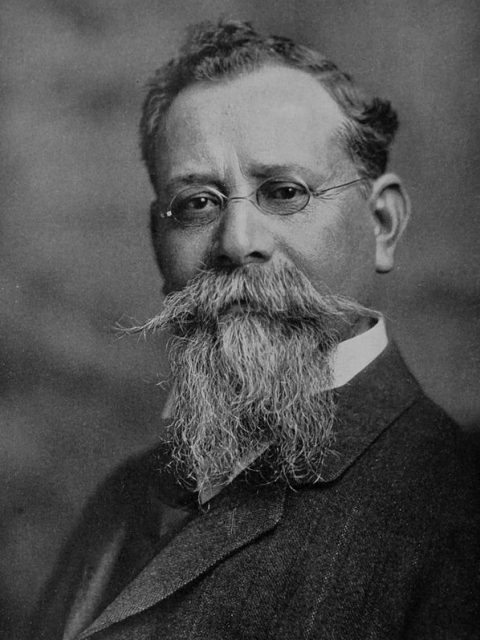

Woodrow Wilson had first supported the opposition government of Venustiano Carranza, but once Carranza was actually elected as President of Mexico, the relationship soured. The U.S. then backed yet another insurrection in Mexico. This one was led by Pancho Villa.

For whatever reason, Wilson came to terms with Carranza and shortly thereafter removed all support for Villa’s band of revolutionaries. Villa’s response was to demonstrate just how poor a decision Wilson had made. Wilson, of course, reacted by summoning the U.S. armed forces.

Wilson then approved the Punitive Expedition, releasing adequate military forces to the cause. And so on March 15th, 1916, the hunt for Pancho Villa began.

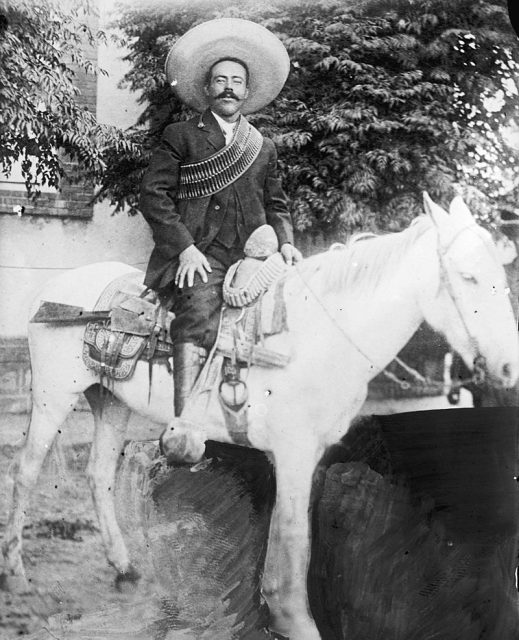

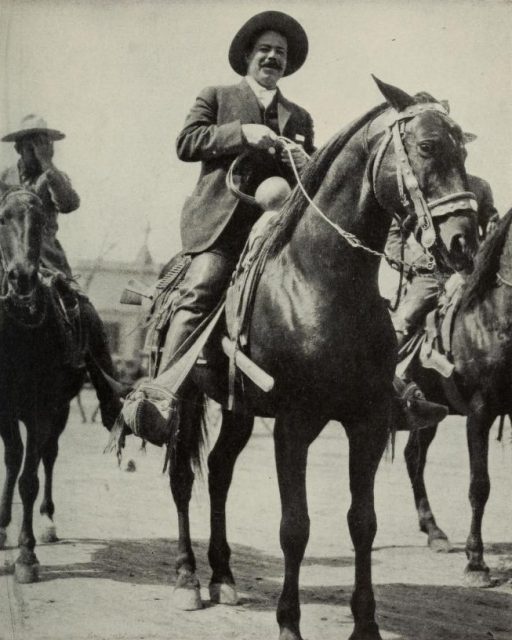

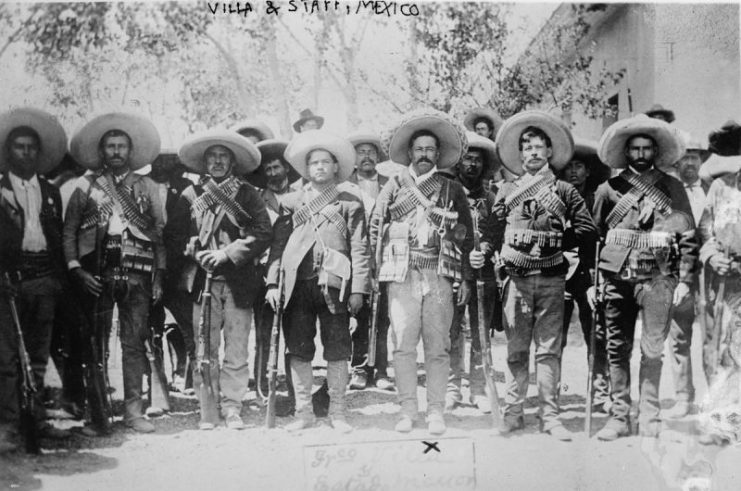

Pancho Villa, whose early life was described as “shrouded in mystery,” was an embittered Mexican revolutionary general, who had since 1915 been a bit of a problem to Mexico. Following the resignation of ex Mexican leader, Victoriano Huerta in 1914, Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza had turned from allies to bitter rivals, battling each other for the succession of Mexican leadership.

He suffered defeat to Carranza at the battle of Celaya, and afterward, he faced Carranza again, at the battle of Agua Prieta. He lost, again. But his bitterness would burst right through him when it was known that the Carrancistas received aid from the U.S.

U.S President Woodrow Wilson had sanctioned the provision of railway passage through the U.S., from Texas to Arizona, enabling movement of about 5000 Carrancista forces to fight Pancho Villa at Agua Puerta. And had also in October 1915, recognized Carranza as the new leader of Mexico.

Villa, after his defeat, was livid at the U.S. government. So he launched a series of attacks on the U.S. nationals and their properties in Northern Mexico.

He had his first real encounter with U.S. forces in the battle of Nogales (26 November 1915), during which he was forced to withdraw his troops from an attack on the city.

In early January 1916, 16 Americans were captured at Santa Isabel by Pancho’s Villista forces; they were stripped of all they had and ultimately executed. This would put every American in Northern Mexico on their heels, but Pancho was willing to take his shenanigans beyond Mexico’s borders.

U.S. General John J. Pershing received a heads-up from local sources that there was an attack heading towards U.S. soil, an attack that would force the hands of the U.S government, and also rub mud on Mexico’s face. This report was taken casually because raids were frequent in those days.

But by 4 am on March 9th, 1916, Villa’s troops surged into Columbus, burning and plundering the town, and causing both military and civilian casualties.

Despite killing 10 civilians and 8 soldiers and injuring 2 civilians and 6 soldiers, Pancho Villa’s force received the heavier blow.

Having stormed a city which held about 240 soldiers of the 13th Cavalry regiment of the U.S. Army, they were engaged in a massive exchange of hostilities especially by the machine gun troop of the 13th Cavalry regiment who set up its machine guns along the north boundary of the Camp Furlong, firing over 5000 rounds apiece and killing many of Villa’s men.

Villa would retreat with his forces, which had suffered about 67 deaths and dozens of injuries, but considerable damage was done to the city of Columbus, and smoke rose into the skies, filling the air with ash from the ruins they left behind.

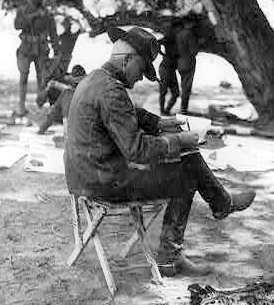

General Pershing, under the orders of the U.S. president, assembled a total force of nearly 6,000 men for the operation which was termed the Punitive Expedition. His force was comprised primarily of cavalry and horse artillery, armed with Springfield rifles, semi-automatic pistols, and machine guns.

The 1st Aero Squadron was included in the mission, sending eight Curtis JN3 airplanes from San Antonio, Texas to Colonia Dublán to serve in reconnaissance operations. On the 18th of March, just after midnight, Pershing dispatched his first unit, the 7th Cavalry, to begin the pursuit.

He would later send the 10th and 11th Cavalry to join. Four additional ‘flying columns’ were also dispatched through the mountains to aid the original three in the pursuit, but the harsh winter weather of late March and early April made pursuit and logistics increasingly difficult.

In late April, an additional cavalry regiment and two infantry units were added to the expedition.

Carranza’s administration struck up a dispute with the American government over the use of the Mexico North Western Railway to send troops and military supplies, so the U.S. army was forced to improvise, making use of trucks to convey supplies. This marked the first time the U.S. army ever made use of trucks in its operations.

Despite the U.S. Army’s preparations, Pancho Villa received a tip six days ahead regarding the expedition. He split his forces into smaller bands and vanished into the trackless mountains.

On March 29th, 1916, while Pancho Villa and his men were celebrating a victory over a Carrancista garrison in Guerrero, they were met by Col. George A. Dodd and his 370 men of the 7th Cavalry.

During the ensuing battle, Villista forces suffered about 70 casualties before fleeing in different directions into the mountains. Villa was nearly caught in this event, and this was the closest the U.S. Army ever came to capturing him.

A group of Villista forces while retreating from Guerrero encountered the 10th Cavalry at a ranch near Agua Caliente. The ensuing engagement would become the first mounted cavalry charge by U.S. troops in the expedition.

The Villistas broke into even smaller groups fleeing over a wooded ridge. The cavalry, led by Major Charles Young gave pursuit, which lasted until dark. By the end, only two Villistas were dead while the rest escaped.

With no success at apprehending Pancho Villa, Pershing’s column pushed deeper into Mexico in their expedition. This sparked even more displeasure from the Carranza administration.

On April 12, 1916, Troops K and M, led by Major Frank Tompkins, were challenged by about 500 Mexican troops in the town of Parral, located 513 miles deep into Mexico following civilian protests of U.S. intrusion into Mexico.

U.S. troops had earlier been advised not to engage in any combat with troops of the Mexican government to avoid any possibilities of war between the two countries. They fell back using a rearguard to keep the Carrancistas at a distance while they retreated.

The skirmish resulted in 2 deaths and 6 injuries on the U.S. side. This would hint at the high possibility of war between the two countries, but a series of diplomatic conversations between the two sides would eventually avert war.

However, despite Mexico’s complaints about the indignity of chasing one man in foreign territory and the (albeit unintentional) ‘abuse’ of Mexico’s sovereignty, the Wilson administration did not withdraw its troops from Mexican soil. This was to prevent being seen as too weak and yielding to Mexico’s pressure.

Pershing on April 21 ordered the withdrawal of his troops from Parral down to San Antonio De Los Arenales. While Dodd’s men were executing the withdrawal order, they met with a band of about 200 Villista forces at Tomochic. Hostilities ensued.

The Villistas fired bullets from the surrounding mountains while Dodd’s troop gave a reply of equal measure. The hostilities continued until dark, and reportedly resulted in 2 deaths and 4 injuries for Dodd’s forces and about 30 casualties on the Villistas side.

On the 5th day of May, another encounter was made. A small Carrancista garrison at Cusihuiriachic was overrun by Villista raiders, prompting the garrison commander to call for help from nearby U.S. troops in San Antonio.

Major Robert L. Howze, in response to the call for help, assembled six units of the 11th Cavalry, its machine gun platoon and a detachment of the Apache Scouts on a night march towards Cusihuiriachic. In the ensuing encounter, 44 Villistas were reportedly killed without a single U.S. casualty, which would constitute the greatest success recorded during the Punitive Expedition.

Several other skirmishes were fought in Glenn Springs, Boquillas, Castillion, San Miguelito Ranch (where America’s first motorized military action took place), and near Las Varas Pass.

On May 9th, a meeting was held between the U.S. and Mexico. Carranza’s Secretary of War and Navy, General Álvaro Obregón, threatened to attack the expedition’s supply line and force it out of Mexico if they wouldn’t leave immediately. This prompted orders from headquarters, gradually withdrawing Pershing’s troops from regions in Northern Mexico.

On June 21, the last engagement of the mission occurred. While Troops C and K of the 10th cavalry were sent to observe Carrancistas along the Mexican Central Railway, they were blocked by about 300 Carrancista soldiers and in the skirmish that followed, were defeated. The U.S. Army lost Captain Charles T. Boyd, 1st Lt. Henry R. Adair and ten enlisted men; another 10 soldiers were wounded and 24 were captured.

General Pershing, on receiving the news, requested permission to conduct a retaliatory strike on the Carrancista garrison in Chihuahua, but President Wilson refused, knowing that the outcome would be a full-blown war.

In the next six months, following further negotiations between Mexico and the U.S., Pershing’s forces were called back. By the end of January, Pershing and his soldiers were on their way back home.

Despite killing several Villistas in all the battles fought during the expedition, the U.S. expedition never captured Villa and failed to put down his uprising. The expedition was a failure. U.S. relations with Mexico had disintegrated and Pancho Villa was still running free.

However, the Punitive Expedition recorded some significant events in America’s military history. The first use of aircraft and trucks in U.S. military history occurred in the Punitive Expedition, and it served as a “warm up” for the U.S. involvement in World War I.