Malta is a small island in the Mediterranean Sea, consisting of 95 square miles strategically located between Italy and Libya. It became a British colony in 1815 and from that point onwards was an important naval base for the British.

With the coming of World War II and Italy entering the war on the Axis side in June 1940, Malta became even more significant. A great deal of crucial war material was being sent via sea convoy through the Suez Canal. The convoys then had to traverse a hazardous Mediterranean route before heading north to Great Britain.

As the convoys crossed the Mediterranean they had to contend with the continuous threat of aerial bombardment, submarines, surface raiders and fast attack boats from all directions.

To make matters worse, the British Royal Navy was stretched to the breaking point from having to protect convoys traveling across the North Atlantic, as well as defending the homeland from the possible threat of invasion. It also was trying to counter Japan’s spectacular success in the Pacific theater of war.

As a result, in the summer of 1940 Malta was poorly defended, with a weakened squadron of just twelve Sea Gladiator biplanes and a handful of anti-aircraft batteries with which to defend itself. The situation looked hopeless, as there was little prospect of reinforcements and the island was within easy striking distance of Italian bombers based at Libya and Sicily.

Malta grew more and more isolated between June and December 1940, when intense fighting broke out along the Libyan and Egyptian border as the British and Italians fought for control of the region. This signified the beginning of the North African campaign.

At the very start of the campaign, Italy considered invading Malta, but dismissed the idea as impractical. They felt that their navy, the Regia Marina, was ill-prepared to carry out such a task. They also wanted to avoid an all-out confrontation with the British Royal Navy.

Unknown to the Italians at this stage of the war, the British saw Malta as a lost cause and had resigned themselves to the idea that they would most likely lose the island early on in the war.

Since the Italians also overestimated the military forces on the island and the resolve of the British to reinforce it, they initially decided to ignore the island and let it be slowly starved into submission.

Italian shipping of supplies to Libya steadily increased over the year from around 37,000 tonnes a month at the beginning of 1940 to just over 49,000 tonnes by the end of the year.

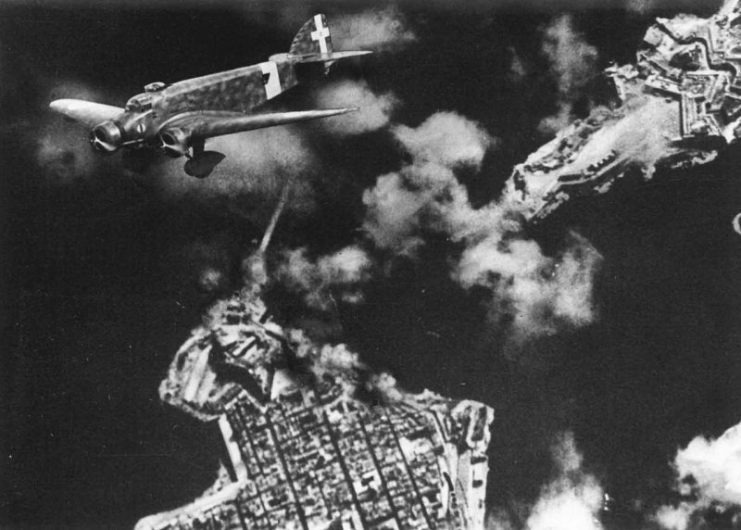

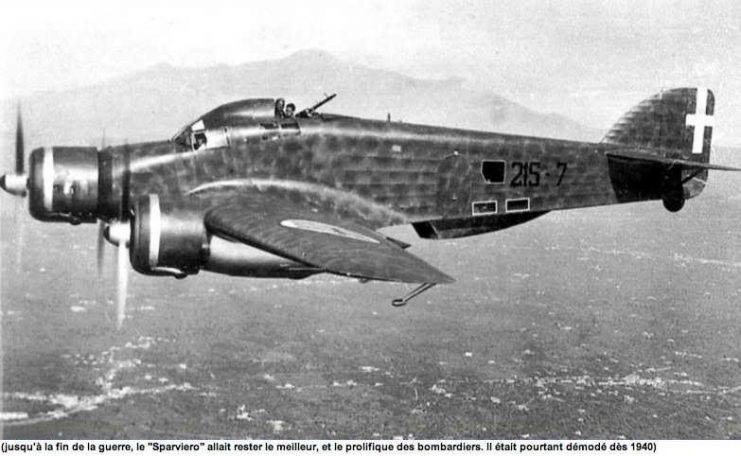

Italian bombing raids on Malta during the summer of 1940 were carried out by medium bombers with a heavy fighter escort. The Italians would normally carry out their bombing at around 20,000 ft. This was blanket bombing, designed to terrorize the local population rather than hit any particular target.

At first neither side was particularly effective. The British Sea Gladiators had some limited success, but were not available in sufficient numbers and struggled to intercept the high flying and quick aerial raiders.

But by the end of the summer, Malta’s defenders had acquired Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers and Hawker Hurricane fighters. Though there were problems with spare parts and maintenance issues, these aircraft quickly made their presence felt. By the end of the year Malta’s pilots claimed to have shot down 45 Italian aircraft and damaged nearly 200 more, as well as sinking an Italian destroyer off the coast of Sicily.

In November 1940, using Fairey Swordfish launched from the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, the British attacked the Italian port of Taranto. The torpedo bombers surprised the ships of the Regia Marina which were anchored up in port. Despite heavy Italian defenses, the Swordfish damaged three Italian battleships.

This was half the Italian battleship fleet, and though most of the damage was quickly repaired, the attack had a profound psychological effect on the Italian High Command.

It made the Italian Navy more hesitant to commit the Regia Marina into an outright confrontation with the British, which indirectly took some of the pressure off Malta.

Despite all this, North Africa was still very much a side show, with little German involvement and Britain making the supplying of troops there a low priority. But 1941 brought about a sharp increase in the intensity of fighting in the region. Both sides started to realize the growing importance of the North African campaign.

The Luftwaffe started to get involved with the conflict, with large number of Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers. They carried out multiple attacks on the HMS Illustrious, which was berthed at Malta at that time. Though the Illustrious was only damaged, it made the British realize how skilled and determined the German pilots were.

In February 1941, the Germans deployed the Afrika Korps under the famed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in order to help their beleaguered allies the Italians.

As the fighting in North Africa intensified and the balance of power there swung back and forth between the Allies and the Axis during 1941, the situation around Malta became intense and almost chaotic.

At first Malta was more harassing the enemy than inflicting heavy casualties on them. Malta-based submarines were heavily hampered by the Italians who were putting down huge numbers of mines around the island and the Tunisian coast line.

But as the year went by the British became more successful at attacking Axis convoys and assisting in getting Allied convoys through. The Germans were forced to withdraw some of their units to the Balkans at a time when Malta’s forces were considerably increased, especially in the form of aerial capability.

As the German impact was starting to be felt in North Africa, this meant there was an ever increasing need for men and materials. This need became even more crucial as Rommel set about besieging the strategically important seaport of Tobruk.

It quickly became apparent that Rommel did not have enough troops to take the port. Rommel’s situation was even more complicated because his supply lines, which ran from the Egyptian border town of Sollum all the way back to the Italian ports, were vulnerable.

Along this vulnerable route lay the Island of Malta, which was constantly threatening Rommel’s supply lines. He felt that Malta could no longer be ignored, but he was overruled. It was decided to continue with the Axis campaign of besieging the island by attacking any convoys heading there, as well as trying to bomb it into submission.

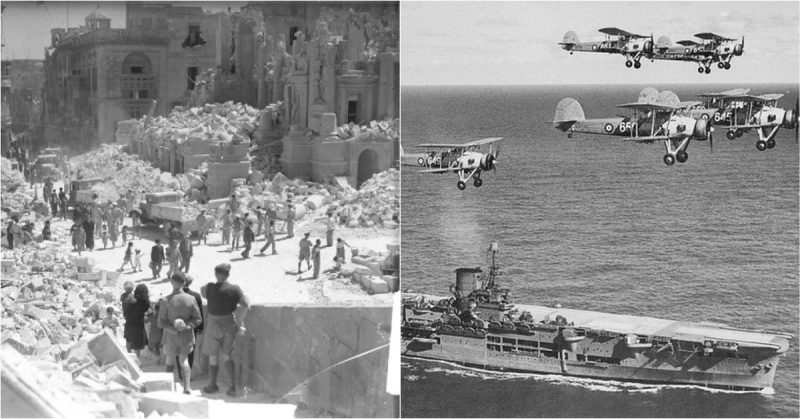

Therefore the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica ended up flying over 3,000 missions to try to destroy the military defenses and morale of the island’s defenders. The idea by now was to either force the island to surrender or pave the way for an invasion.

By the summer of 1942, many things had changed. The Axis seemed to be winning in North Africa with Rommel’s victory at Battle of Gazala and the fall of Tobruk, which caused the British to retreat into Egypt. So Hitler and Mussolini, enthusiastically supported by Rommel, approved the planning of Operation Herkules, the invasion of Malta.

Major General Kurt Student, Knight’s Cross recipient and the highest ranking officer in Germany’s parachute infantry, was assigned the task of leading the invasion of Malta.

He had excellent intelligence concerning the island, as the Italians had carried out extensive aerial reconnaissance of the island’s fortifications, emplacements, and military assets.

Student was eager to learn from any mistakes the Germans had made during the highly successful invasion of the Greek island of Crete back in May 1941. Despite its success, the Germans had lost a large number of men, especially in the parachute units.

Student devised a plan for attacking Malta using a combined force of Italian and German units. The initial attack would use a force numbering 700 transporters planes with over 500 gliders landing around 29,000 airborne troops.

By now the Malta garrison had been heavily strengthened. It was composed of 20,000 troops backed up with armored detachments, as well as extensive air defenses and heavy shore batteries.

Because of these defenses, Student felt the airborne units would need to be followed up with a massive amphibious landing comprised of 700,000 Italian troops supported by large numbers of Italian and German armor, including captured Soviet equipment.

Student’s plan called for massive resources that simply were not there. Events like the commitment of Germany’s Army Group B at Stalingrad and the Axis defeat at the Second Battle of El Alamein in November 1942 caused the Axis no end of problems.

This was compounded by the Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa. The Axis were now fighting a war in North Africa on two fronts against an enemy increasing in strength at a time when the Axis forces were diminishing dramatically in numbers.

Also, in the summer of 1942 the Maltese started to receive Supermarine Spitfires and quickly gained air superiority at the same time that Axis raids were just starting to have a detrimental effect on the island’s military capacity.

Previously, Italian bombers had been getting daring and carrying out highly effective low level attacks. But with the Spitfires’ arrival and the implementation of a new tactic called the Forward Interception Plan, the RAF quickly dominated the Maltese sky and the Axis were forced to scale back their operations, from which they never recovered.

With renewed confidence, in December 1942 air and sea units operating from Malta went on the offensive. Over the next 6 months they sank over 200 Axis ships.

So any idea of invading Malta was permanently shelved as the Axis fought for their very survival in North Africa. Their situation continued to deteriorate, and in May 1943 Axis troops in Africa were forced to surrender. Hundreds of thousands of their troops and vast amounts of their equipment were captured.

Shortly afterward, in July 1943, Italy was invaded by the Allies. By September, Italy had signed an armistice and had switched sides, declaring war on Nazi Germany.

Read another story from us: The Failed Secret Mission to Convince Italy to Abandon the Nazis

For its part, the Island of Malta was awarded the George Cross medal for the bravery and sacrifice of its people during the siege. This was the only time in World War II the George Cross was awarded collectively rather than to an individual.

Because of this honor, since 1943 the George Cross symbol has been incorporated into the flag of Malta.