Ultimately, Charles’ invasion of England accomplished little.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 threw the entire course of British life and monarchy into chaos. Like many sweeping social and governmental changes, the results were often unpopular and led to fierce resistance. The British found themselves at a crossroads and repression and violence were inevitable. The unrest culminated in the Jacobite Uprising of 1745.

Religion and the Divine Right of Kings

Who exactly were the Jacobites? The most basic answer is that the Jacobites were loyal to King James II of England (James IV in Scotland) and his descendants. The term Jacobite comes from the Latin form of James – Jacobus.

James was deposed in 1688 after William of Orange, James’ nephew and son-in-law, arrived with an army to claim the throne. James fled the country, with many nobles interpreting this act as him relinquishing the throne to William III, who became co-ruler with his wife, Queen Mary II.

However, the Jacobites believed that James’ removal was illegitimate. The Jacobites argued that monarchs received their authority from God via the Divine Right of Kings, meaning that their authority could not be revoked by their subjects or parliament.

There was also a significant religious subtext to all this political maneuvering. James was Catholic and generally tolerant of Protestants, while William and Mary were militant Protestants and began repressing Catholics after taking the throne. Catholics were banned from voting, serving in Parliament, marrying non-Catholics, and were also stripped of other rights.

The Scots’ Angle

Scotland and northern England were the most Catholic parts of the Kingdom at the time. John Graham, the Viscount of Dundee, was a Jacobite and began rallying forces in the Highlands to resist the new rulers. Unsurprisingly, he found many Catholics who were outraged at their loss of power and rights. Under such conditions, armed conflict was inevitable.

The first Jacobite Uprising began in 1689. The uprising achieved a victory at the Battle of Killiecrankie, although John Graham was killed towards the end of the battle and the rebellion soon fell apart. A few years later, a further revolt in Ireland was crushed. It appeared that the Jacobites had been soundly defeated.

The 1707 Act of Union united the crowns of England and Scotland under Queen Anne. Some Scots already recognized the Jacobite cause as a natural continuation of their historic conflict with England.

Memories of the long-standing Auld Alliance between Scotland and Catholic France were brought to mind as the French launched several abortive invasions to help restore James’ heirs to the throne. Once again, many Scots found themselves alongside the French in opposition to the English. To a degree, the Scottish Jacobite cause also became pro-independence and pro-Catholic.

1745

After a failed 1696 Jacobite assassination attempt on William and more unsuccessful uprisings in 1715 and 1719, the Jacobite cause seemed lost. Yet after several decades of peace, James II’s great-grandson, Charles III, arrived in Scotland to lay claim to the throne. In July 1745, “Bonnie Prince Charlie” arrived in the Outer Hebrides and gathered significant support.

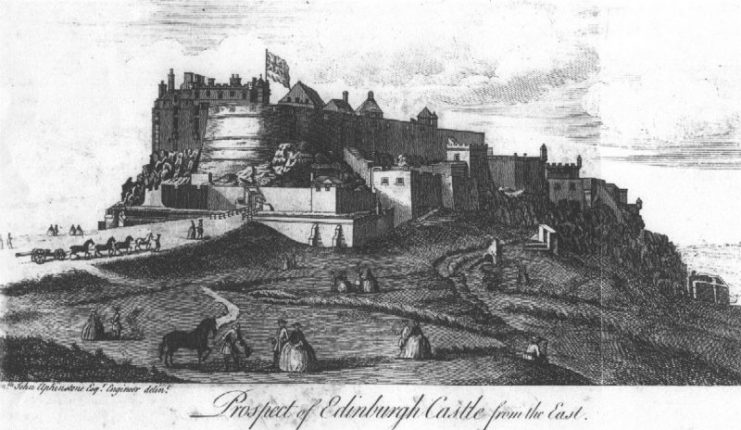

By September, the Bonnie Prince and his army had managed to take Edinburgh without a fight. Although the government maintained control of Edinburgh Castle, James III, Charles’ father, was crowned King of Scotland with Charles III as his regent. Charles publicly renounced the union with England and shocked many Scottish leaders by preparing an invasion force.

Charles’ invasion of England went well at first. He crossed the border with no resistance and easily captured several forts, small towns, and even a number of cities. Nonetheless, the Jacobites were troubled by the local population’s reluctance to join them.

The cause received little support even from cities that were Jacobite strongholds during the 1715 uprising. For example, only three men joined from the town of Preston. Manchester stood out as the only exception and contributed several hundred men to the cause.

The Jacobites’ military leaders realized they were in danger of being cut off from Scotland if they continued south and eventually decided to retreat north. Ultimately, Charles’ invasion of England accomplished little.

Height of Power and Fall of the Rebellion

On returning to Scotland, the Bonnie Prince and his men set about consolidating their position. They took several towns occupied by troops loyal to George II of England but ran into resistance at Sterling Castle. Charles led the siege himself, but a relief force soon arrived from England.

Under General Henry Hawley, the English sent an advance force in an attempt to relieve the castle. Believing that the Jacobites would take up defensive positions, Hawley left his army encamped on January 17th, 1746 and made his headquarters at a mansion 2,000 yards away. Instead of waiting, the Jacobites decided to attack.

Hawley failed to realize the attack was coming until the battle had almost begun. He even disregarded early reports of the approaching force, meaning that his men and guns were out of position. A heavy downpour then hampered their ability to organize themselves.

After decimating Hawley’s cavalry charge, the Highlanders launched their famous “Highland Charge.” They fired a single volley before dropping their guns and charging with swords through a wild wind and heavy rain. The English were driven from the field.

However, their success was to be short lived. The armies met again at Culloden in April. The government forces were led by Prince Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, while Charles commanded the Jacobites.

The Jacobite army faced several disadvantages. First, they aborted a night attack on the 15th upon realizing they would have difficulty avoiding government patrols. Secondly, the already tired Jacobites had to fight across a moor which limited their troop movement. Finally, the Duke of Cumberland was aware of his artillery advantage and began bombarding the Jacobites.

The Jacobite army took substantial casualties from Cumberland’s cannons. Some began charging without orders instead of waiting to be killed. As they trudged across the moor, the improvised highland charge ran into canister shot and multiple volleys of musket fire.

A few highlanders managed to break through the first enemy line, only to find more lines of government soldiers waiting for them. The Jacobite forces soon retreated, having lost about a third of their force.

Aftermath

Although some fighting continued for years after the Battle of Culloden, the Jacobites were essentially defeated. Charles ordered his remaining men to disband before fleeing to France. Despite ostensibly seeking more support for his cause, he would never return to Scotland.

The Bonnie Prince’s reputation was ruined, not just by military failure, but also by his heavy drinking and frequent fights with other Scottish leaders. He had already lost much of his support, and he might not have been entirely welcomed back anyway. Charles died in Rome in 1788.

The final Jacobite uprising of 1745 was a complete disaster, both for Catholics and the Scots. The English Parliament responded to the Scottish support for the uprising with various laws aimed at repressing Gaelic culture. Traditional highland dress, including kilts and tartans, was banned in 1746.

Meanwhile, all Scots were forced to turn over their weapons and forts were constructed to prevent future rebellions. Finally, the clans were stripped of many of their traditional rights, while lands were seized from those sympathetic to the Jacobites.

Read another story from us: Butcher Cumberland & the Last Highland Charge – Battle of Culloden

Although the Jacobite cause would never return as a serious force in British politics, there was a brief Jacobite revival in the late 1800s. This revival lost popularity as monarchies across Europe collapsed during the Second World War, but some Jacobites remain to this day.

The Royal Stuart Society continues to advocate for the monarchy, believing that Parliamentary Democracy and Republicanism should be abolished. Modern-day Jacobites recognize Franz, the Duke of Bavaria as the legitimate heir to the Stuart throne, despite his refusal to make a claim to it.