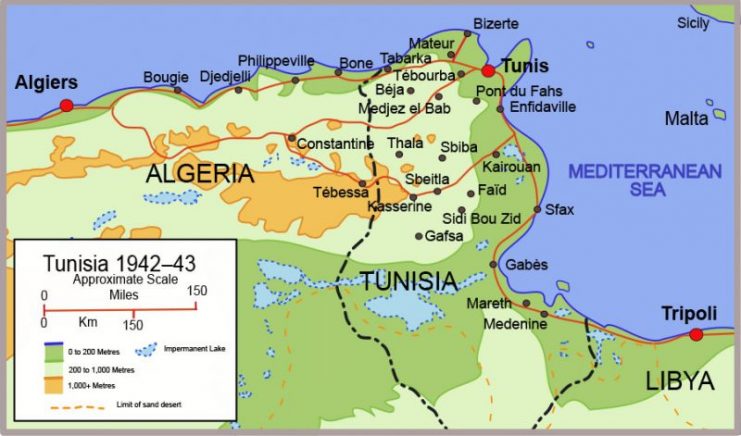

During the Second World War, the fighting in Tunisia was all about control of the supply lines. There were a limited number of passes which allowed for adequate communication and movement of supplies through the imposing mountains that marred the otherwise flat plains.

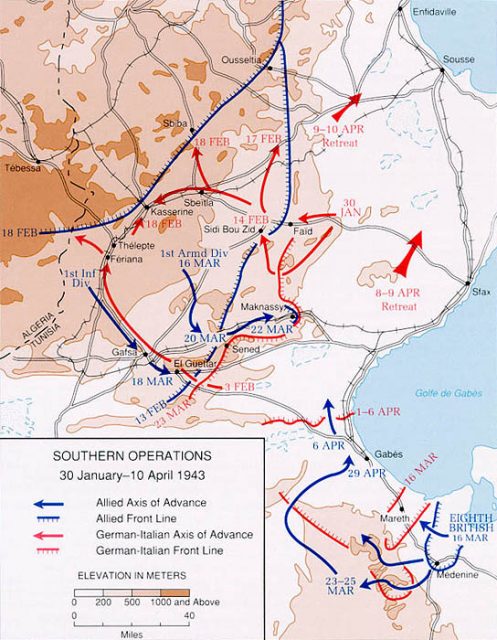

On January 30, 1943, the German forces launched an attack on the French who were holding the Faïd Pass in Tunisia.

The ensuing battle not only demonstrated one of the key weaknesses of the Allied troops in North Africa but also displayed the decisive action the Germans were capable of, even as the tides of the war were turning back to drown them.

A little over a month prior to the attack, the Faïd Pass fell to Allied forces. This occurred less than a month after the Americans had arrived on the scene to invade the Axis-dominated Tunisia. The French, aided by American paratroopers, had conquered this strategically important position.

Acquisition of the Pass dissected Axis forces between the airbase at Thélepte and their supply base at Tébessa. As such, holding the Faïd Pass was vital to keeping Thélepte and maintaining Allied air superiority in the region over eastern Tunisia.

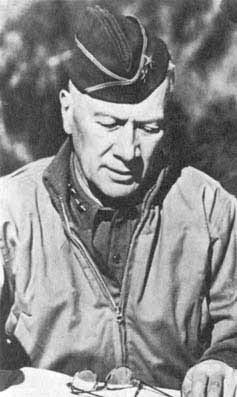

The commander of the American II Corps, Major General Lloyd Fredendall, decided against reinforcing the French troops in the region, forcing them to hold the pass without any support from the Americans. His belief was that an attack on Maknassy would draw off any German forces and so prevent aggressive action against Faïd. He was wrong.

The Axis forces pulled back from their positions further east as the Americans advanced through Tunisia. Rommel’s Afrika Corps had found themselves wedged between their old foes, the British and the new American upstarts with the Operation Torch landings.

He courted confrontation with these enemies by retreating into Tunisia to make his last stand in North Africa.

So it was that Rommel and his most experienced veteran troops arrived near the Faïd Pass with their eyes on engaging the French.

The first veteran unit to reach Tunisia was the 21st Panzer Division, supported by a motley crew of Italian and German forces from the Fifth Army.

The assault was carefully staged: a two-pronged attack fell on the French from the east, while another strike from the southwest caught them in the rear, bringing the full power of Rommel’s Panzer tanks to bear on his foes.

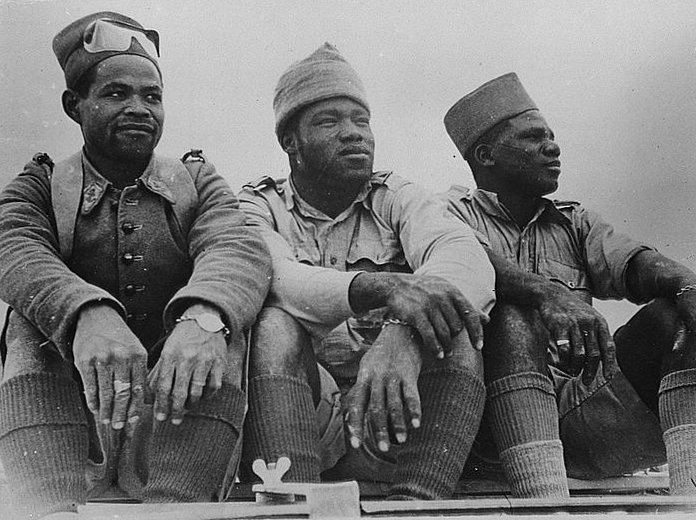

The fighting was fierce, with the French unwilling to give up the territory they had recently reclaimed.

They held onto the pass despite the overwhelming presence of their enemies. However, they were outgunned, outnumbered, and fighting savagely against men far more experienced in warfare. They needed assistance.

With the twin threats of defeat and annihilation tugging at their morale, the French sought out the Americans for support.

Then they dug their heels in against the constant shelling and waited desperately for the armored cavalry to arrive and liberate them.

Based in Sbeitla, some thirty miles to the west of Faïd, Brigadier General Raymond McQuillin and his Combat Command A heard the call. On January 30, he received indecisive orders from Fedendall.

There was something about a counterattack at Faïd Pass to restore the French to power there, but he also received orders not to compromise the defenses at Sbeitla. In essence, the contradictory orders were to attack but also to stay put.

He made a decision and deployed a company of tanks to scout out the situation within a half hour.

Once McQuillin had done his reconnaissance, he sent out a much larger force of tanks, artillery, and armored infantry to accompany the previous company of tanks into the combat zone.

High above the desert, Axis planes turned on the American column, and the soldiers from Combat Command A took enough heavy losses to make McQuillin think twice about the counterattack. He decided to launch it the next day.

The Americans took that night to prepare while the French clung to their position. Finally, at 7 a.m on New Year’s Eve, McQuillin sent his men out to attack once again.

This time, a few German tanks rode out of the pass to meet them, but then promptly turned back, retreating before the might of the American forces. American tanks gave chase and rode right into a trap.

Throughout the night, the German and Italian forces had also been preparing themselves.

They had concealed tanks in gullies while also positioning heavy machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns in hastily made emplacements.

Nine American tanks were destroyed in minutes, and the survivors retreated. Further south, another of McQuillin’s attacks was also broken and driven into retreat.

All hope for the French seemed lost, but the Americans had one more card to play before the game was up. That card was Colonel Robert Stack’s Combat Command C who diverted their advance on Maknassy at the behest of the French.

Stack had been given a series of contradictory and nonsensical orders, the same as McQuillin. He had been ordered to advance on Sidi Bou Zid, a village close to the Faïd Pass.

He set out for Sidi Bou Zid on the morning of the 31st but reversed course in response to orders that pulled him back to Maknassy.

In desperation, a French general asked him to double-check his orders, but they remained the same. Fredendall had the mistaken idea that McQuillin’s troops had taken control of the pass, and this mistake was reflected in his orders to Stack.

Read another story from us: The Desert Fox’s 1st Encounter with U.S. Forces

The biggest problem facing the Allies in Tunisia was the lack of coordination, as demonstrated by the catastrophic events at the Faïd Pass.

Thanks to Fredendall, the French waited in vain for the support they so desperately needed. Ultimately, despite their strong, valiant resistance in the face of overwhelming firepower, they were overtaken.

This blunder cost Fredendall his position after the French protested to the Americans, but that was ultimately little comfort to the men who died defending a pass, waiting for support that would never arrive.