In the Vietnam War, a lone Green Beret single-handedly saved a South Vietnamese town during the Tet Offensive.

Initially rejected for special service due to being too young, by 1968 Drew Dix eventually rose to the rank of Staff Sergeant and joined the Green Berets.

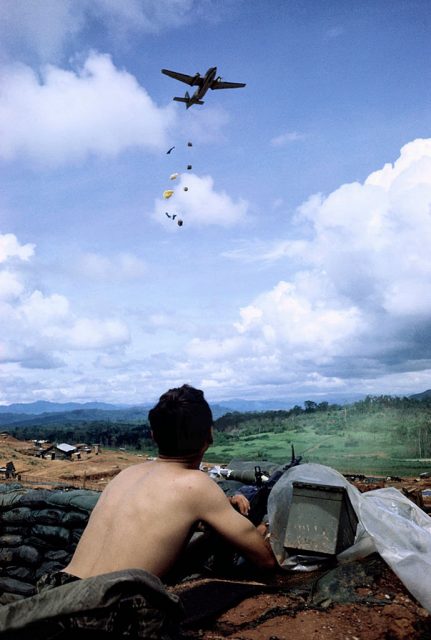

The Vietnam War had entered a decisive phase with the commandeering General Westmoreland promising they were closer to victory than ever. But the Tet Offensive, which occurred during the Vietnamese New Year in late January 1968, caught American forces off-guard.

Drew Dix was serving as a unit advisor for South Vietnamese forces when two heavily armed battalions of South Vietnamese guerrillas attacked the provincial capital of Chau Pu.

With the defenses fragmented, S Sgt. Dix led a patrol to assist in the defense of the city. He started by organizing a relief force, rescuing a nurse trapped in a house near the center of the city, and transporting her to the tactical operations center (TOC).

Hearing news of yet more trapped civilians, he again volunteered to lead a rescue force.

Under heavy mortar and intense machine-gun fire by large groups of Vietcong, he personally led the assault on the building, killing six Viet Cong and rescuing two civilians.

The next day, he gathered an ad hoc force of 20 men to clear a hotel, theatre, and adjacent buildings in the downtown area.

Inspired by his bravery, South Vietnamese soldiers rallied and helped S. Sgt. Dix capture 20 prisoners including a high ranking official. Dix led his force to clear the residence of the Deputy Province Chief. He also successfully rescued the official’s wife and children.

While responding to continuing attacks over the course of several days, S. Sgt. Dix’s heroic actions resulted in 14 Viet Cong being killed and as many as 25 more being unconfirmed. He captured 20 prisoners, 15 weapons, and rescued 14 American and innocent civilians.

His actions reflect the great irony of the Tet Offensive. Outnumbered, on holiday, and massively surprised, United States Armed Forces and soldiers like Dix inflicted a considerable amount of damage on the enemy.

The communist forces suffered heavy casualties: an estimated 50,000 Army of North Vietnam and Viet Cong troops were killed, missing, or captured.

U.S. commander, General William C. Westmoreland, viewed the post-Tet situation as an opportunity for an American offensive that would further debilitate the enemy and deny any future resurgence.

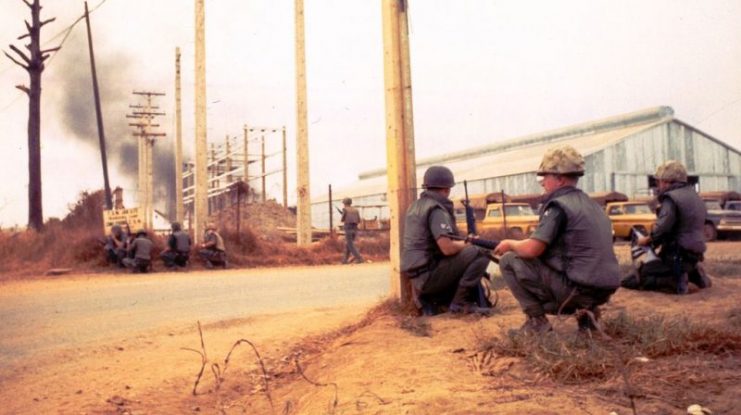

In a similar manner to the disastrous attacks by the Chinese Communists against Nationalist-held cities in the early 1930s, this offensive negated the advantages of the insurgent army, allowed them to be targeted by the overwhelming firepower of American forces, and forced them to defend territory in urban terrain.

By February of 1968, during the height of the counter-attack against the Tet Offensive, American causalities had grown to almost 500 a week.

This was often referred to as the first television war. In February 1968, Walter Cronkite, the most trusted newsman in America, called it mired in a stalemate.

Read another story from us: TeT Offensive – Nightmare for Hue City

The media’s role in influencing adverse opinion about the war is debatable, and it’s possible their negative turn just reflected popular sentiment after February 1968. But the public’s vehement opposition to the war certainly solidified after the Tet Offensive.

As a result, a battlefield victory secured by surprised and outnumbered forces ended up feeling like a defeat which drastically altered the war.