Mankind never seems to tire of finding new and inventive ways of killing one another during wartime.

Not long ago, soldiers were restricted by the technology of weapons. They simply lined up and ran at the enemy with bayonets until the last side standing declared victory in a particular battle.

But when World War I descended, those limited weapons and tactics gave way to modern military innovations. Defense contractors came up with inventions like tanks, which meant armies could attack with greater speed and efficacy.

Soon, mining technology was adapted so that the skills of those workers could be applied to battlefields, which led to the battle at Messines (“Mesen” in English) in Belgium in 1917.

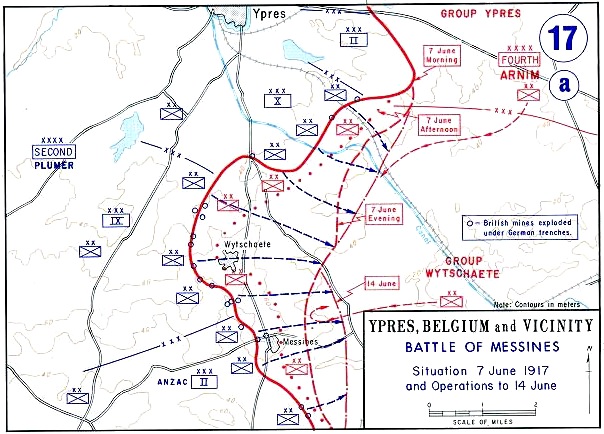

By that summer, the German army was completely ensconced in Messines and had control of a large expanse of flat terrain that swept out from the high ridge of Ypres.

The British forces fought with the Germans for about two years but to no avail. The British simply could not take decisive control of the region, or so it seemed.

Little did the Germans know that for those two years, men from Britain, New Zealand, Australia, and Canada had been digging tunnels underground, as deep as 20 meters in some places, right to the Messines Ridge.

The Germans were also building tunnels, and the opposing forces came within mere meters from one another at times.

For 24 months, the British units had been packing those tunnels with more than 450 tons of gun cotton – Ammonal and Nitrocellulose – and planned to set it off in one monumental blast.

Although these kinds of explosives had been used previously during the war, never before had this amount been readied for use in one place or one blast. If the plan worked, it would result in something never seen or heard in the history of mankind and warfare.

The British forces and tanks moved as stealthily as possible into position, preparing for the explosion and its aftermath as best they could.

The men knew chaos would reign supreme if the blasts went off as planned. According to the online website, Encyclopedia Britannica, “the sound was so loud, the blast from the explosions could be heard in London, some 130 miles distant.”

On June 7, the order was given, and the explosions were triggered. The mines, all stuffed with Ammonal and Nitrocellulose, started to detonate. In total, 19 explosions went off and they lit up the sky.

The entire ridge caught on fire, and 10,000 German soldiers died almost instantly. Those who didn’t were so stunned by these events that many of them didn’t fight at all but just surrendered.

However, as the British forces advanced they did encounter small bands of men who wanted to continue the battle, and so the fight wore on over the course of an entire day.

Ultimately, the Germans had no hope of retaining what they had lost, and the British claimed a decisive victory in the Battle of Messines Ridge.

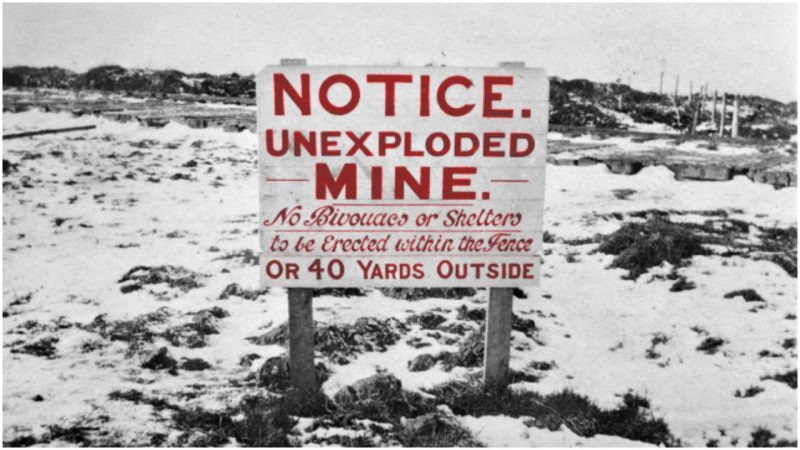

Not every mine exploded that day. Some have remained buried but potentially active for all this time. Once, in 1955, when lightning struck, an explosion was triggered. A farm animal was killed, but fortunately, no people were injured.

But a legacy remains in the scarred soil, in the massive craters which were caused by the explosions and are still visible. They are a reminder that, over the course of two years during the Great War, thousands of men died during a conflict many believed would be the world’s last.

The “War to End All Wars” as it was dubbed at the time proved to be anything but, as about two decades later, another worldwide war was underway.

Read another story from us: Battlefield Gallipoli – From Troy to the Anzacs