When the Special Air Service (SAS) were sent into the territory of Aden in 1964, Britain’s fighting elite found themselves caught up in a messy and unwinnable war.

Britain and Aden

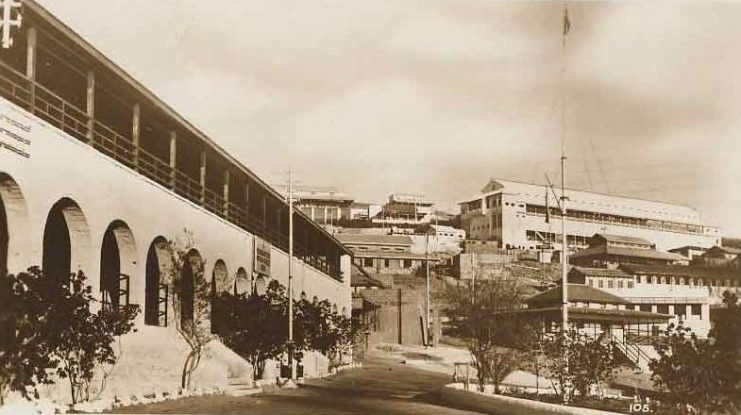

Aden became part of the British Empire in 1839. Over a century later, as the British decolonized in the aftermath of World War II, it grew in importance thanks to the loss of other territories. This Arabian port and the surrounding territory became the headquarters for both the Colonial Office and the British military in the Middle East.

In the early 1960s, resentment rose against the British presence. British troops fought caravan raiders and tried to quell tribal warfare while facing resistance from Arab nationalists both in and outside Aden.

On December 10, 1963, a terrorist tried to kill the British High Commissioner. A state of emergency was declared in Aden and the British ramped up their efforts to retain control.

Arriving in Aden

In April 1964, a small force of SAS troops arrived. These were the days before the Iranian embassy siege and the SAS was still a little-known force. Through campaigns in Malaya, the Middle East, and Borneo, they had developed skills in infiltration, covert warfare, and small group combat. Employed by governments around the world to train security teams, they were among the best Britain had.

But even the best could only do so much.

Adapting Tactics

Under constant pressure from local opponents, British troops in Aden had developed a bunker mentality. They only patrolled close to their bases, allowing the enemy to reinforce themselves, gain ground, and import more weapons.

The SAS also adapted to local circumstances, but in a different way. In their early expeditions, they discovered that insurgents would wait until night and then attack them in camp. From then on, if they went out with other troops, the SAS would sort out their equipment in the new camp and then retreat to nearby hills to watch these futile firefights in safety.

Danaba

One of the first SAS actions in Aden took place less than a month after they arrived when they joined regular troops in an attack on rebels at the Danaba basin.

The mission turned into a disaster. The SAS patrol established a position on a dry and rocky hill but was discovered by rebels after shooting a local tribesman. They spent a day besieged by rebel forces before slipping away under cover of night. Several SAS men were lost in the action. The target they had been after eventually took months to overcome.

Publicity and Denial

The fallout from the attack was equally disastrous.

The heads of two of the dead soldiers were taken into Yemen and paraded through the streets. In response, the major-general in charge of Britain’s Middle East Ground Forces gave a press conference in which he announced the SAS’s presence and denounced the display of the severed heads.

The SAS, which usually worked in the shadows, now faced the harsh glare of publicity. Worse, friends and families of the dead men, who didn’t know that they had even left Britain, learned about their deaths through news stories. The Yemeni government initially denied what had happened. Controversy raged.

Meanwhile, SAS tactics were changed. They would now patrol in large units rather than their normal four-man patrols. While well intentioned, it was a move that hindered their effectiveness.

Covert Operations

The SAS settled into the business of fighting to keep the peace in Aden. Alongside military patrols, they carried out covert and political operations in support of British intelligence.

The intelligence gathering included infiltrating the supply routes Yemen was using to arm the rebels. Arab speakers infiltrated these routes and captives were taken for interrogation.

The political work was an adaptation of the “hearts and minds” tactics the SAS had pioneered in other parts of the world. Cash and guns bought support from locals, who then provided information on rebel movements, leading to successful operations against the insurgents.

Raiders

Some SAS men were employed in a less official capacity. A British-run and Saudi-funded team was put together to carry out covert raids into North Yemen, to attack Yemeni and Egyptian troops there.

While the SAS were not officially involved, some men resigned from the unit, fought as mercenaries in this force, and then returned to the SAS afterward without any consequence. The meaning was clear – the British Army might not officially be carrying out these attacks, but it was letting its best soldiers become part of them. It was the flimsiest screen of plausible deniability.

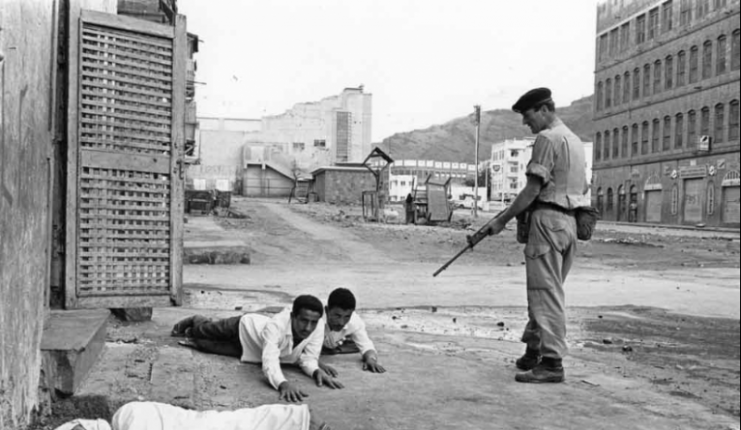

Urban Warfare

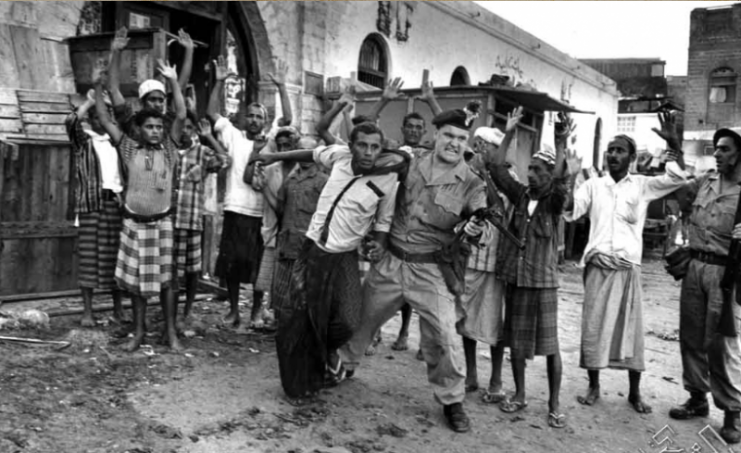

In the Crater district of Aden town, the SAS got some of their first experience of urban warfare. Men who could pass as Arabic with the aid of makeup were formed into disguised patrols that went into the streets of this troubled district. They carried concealed pistols and sought out targets of opportunity among the rebel community.

This resulted in some successful actions, as SAS men gunned enemies down in shootouts. It also resulted in awkward moments, as they were stopped and even arrested by regular British troops.

An Undignified Withdrawal

Soon after the SAS arrived, the British government committed to withdrawing from Aden by 1968. As a result, the regiment was preparing for a retreat almost from the moment it hit the ground. They continued their raids, both rural and urban, and their intelligence work, constantly aware that the end was approaching, that there could be no victory.

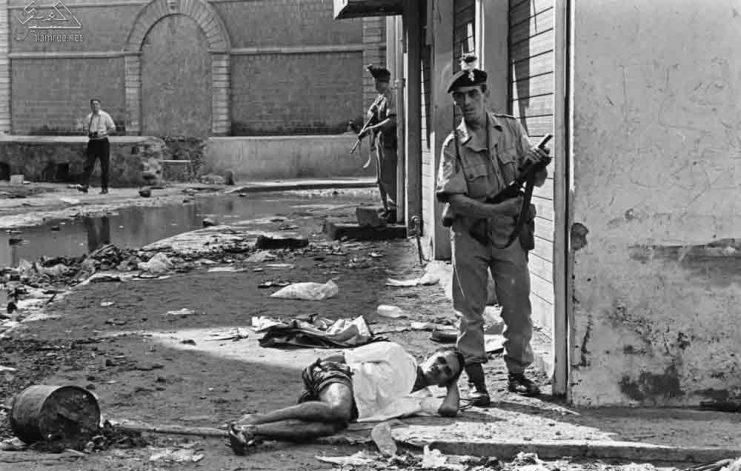

As that end approached, riots and mutiny shook Aden. British troops were massacred by rebels. The British themselves, including the SAS, killed civilians in their struggle to quell terrible violence in the Crater.

In the final days, the British withdrew to the city, then the harbor, and then the airfield, from which the last troops were flown out.

Aden, and by extension Yemen, had been a grueling experience for the SAS. It had also been one in which they applied their unique skills to good effect, and from which they learned valuable lessons. When they were deployed to Northern Ireland soon after, it was the experience of Aden that would prepare them for the challenges of urban warfare amid a hostile population.