The Cold War was an uncertain time for much of the world. There was a permeating fear the Soviet Union would launch a nuclear attack, and countries bulked up their nuclear arsenals as a result. This included the United States, whose government chose to transport such weapons on locomotives called “white trains.”

The development of nuclear weapons during the Cold War

With fears the USSR would launch a nuclear attack on the US, the government focused its attention on building up its own arsenal. The weapons were constructed at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas, a former World War II munitions base. It was a 10,000-acre complex with dozens of buildings, and a large portion of those living in Amarillo were employed there, assembling and disassembling bombs.

Trains and trucks arrived at the plant daily. They carried bomb triggers from Colorado, plutonium from Washington and Georgia, neutron generators from Florida and uranium from Tennessee. Once the material arrived, employees dressed in blue coveralls, safety shoes with rubber slipcovers and thick gloves worked in pairs to assemble the weapons.

After the nuclear material was attached to explosives, they were taken to bays, where workers added tails, firing components and casings.

White trains to transport nuclear weapons

The Department of Energy decided it best to use “white trains” to transport nuclear weapons across the country. These were “safe, secure railcars,” or SSRs, built in such a way that they could withstand an attack. They featured heavily armored boxcars between “turret cars,” through which armed guards stood ready to defend the train.

The white trains moved slowly, at a maximum of 35 miles per hour, and were manned by seven-member crews. While numerous routes were used, there were two primary ones. The first was from Amarillo to Bangor, Washington, where the weapons were delivered to a submarine base in Puget Sound. The second was from Amarillo to Charleston, South Carolina, where they were delivered to submarines tasked with missions in the Atlantic Ocean.

Protests against the white trains

By the beginning of the 1980s, Americans were beginning to express fears over nuclear material being transported across the country. There was one couple in particular, Jim and Shelley Douglass, who decided to take action against the white trains, with the help of a nuclear resistance group called Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action.

The Douglass’ and their associates quickly mapped out the likely route the trains took from Amarillo to Washington. They then contacted protest and religious groups to inform local newspapers and organize nonviolent protests along the railway. Vigils occurred in 300 communities.

The Department of Energy felt the protests posed risks to the operation. Not only did it generate negative press, it meant there was a risk that someone could hijack one of the trains. As well, the DOE didn’t like that attention was being placed upon something intended to be classified.

To rectify the problem, the DOE first tried to reroute the trains, but the protestors caught on. They then proposed new rules that would make it illegal to share route information, but this saw little traction. They finally decided it best to paint the trains different colors – red, green, blue and grey – but the trains were still easily tracked.

Things came to a head in 1985, when the Douglasses and other protestors were arrested and charged with conspiracy and trespassing after attending a protest rally. A Washington jury returned not-guilty verdicts in the cases, leading county officials to announce they would no longer arrest those protesting and blocking the white trains.

Peacekeeper Rail Garrison

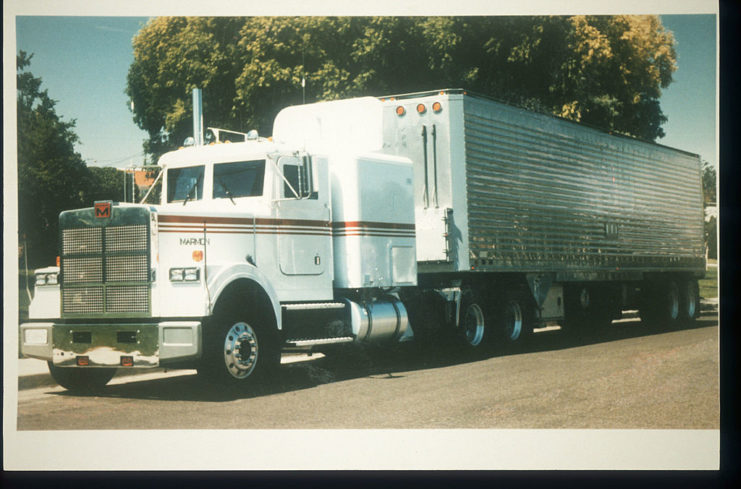

Not long after the court cases in Washington, the Department of Energy began exclusively using Safeguard Transporters to move nuclear material across the US. It was the department’s belief the trucks would be more obscure, as they could reach nuclear sites while keeping away from railways. The white trains were retired and security-sensitive equipment removed, before being placed in junkyards and museums across the country.

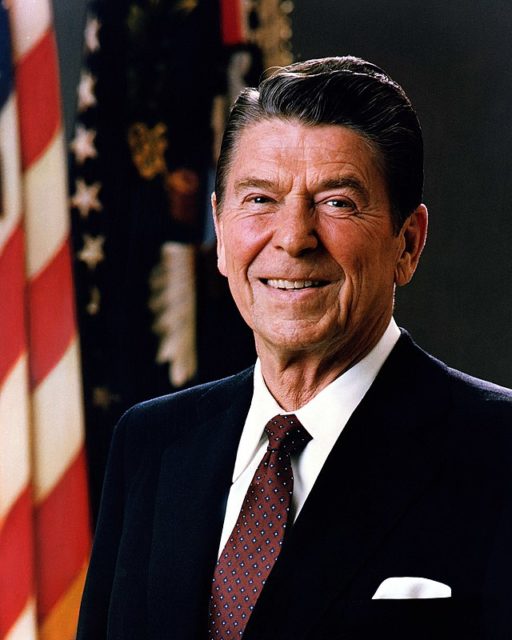

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan approved an initiative known as the Peacekeeper Rail Garrison, which allowed intercontinental ballistic missiles to be launched from train cars. 25 trains carrying two missiles each were parked at military bases throughout the country. If the Soviets made a move against the US, they would be moved onto the nation’s railway network, where the missiles could be launched.

By the late 1980s, the government had developed 120,000 miles of train track, which could be used by 20,000 locomotives with 1.2 million railcars. At any given time, it’s estimated there were over 1,700 trains traveling along the railway.

When the Soviet Union broke up in 1991, the US decommissioned the majority of its nuclear arsenal and made the decision to discontinue projects that were expensive and experimental in nature, including the Peacekeeper Rail Garrison.