When Charlemagne was made Emperor in 800CE by Pope Leo II, it began a complex relationship between church and state as both powers attempted to establish what the new title was meant to represent.

As the Papacy’s power had quickly begun to wane along with the fall of the Roman Empire, the increasingly frail religious institution required a protector and a powerful champion to ensure its survival.

In a rapidly changing world, the church had turned towards the growing Kingdom of the Franks in the north, hoping to reassert its authority before it became obsolete. To do this, the Pope needed to bestow power carefully on his allies while simultaneously maintaining his own position at the top.

It was the beginning of what would eventually be called the Holy Roman Empire. The precarious balance between the Empire and the Papacy would play a major role in European politics and conflicts for the next ten centuries.

Under the Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties, the Empire and the Papacy had managed to walk this tight-rope and maintain a harmonious relationship by recognizing each other’s title and authority.

The Frankish and Germanic kings played their part by defending the church, often militarily, from enemies that sought to undermine or usurp Papal control within Italy. In return, they would be crowned king of both the Franks and the Italians, forming a united kingdom meant to safeguard Rome and Christianity.

When Otto I assumed this role and its duties, Pope John XII cemented this relationship by crowning him Emperor in 962CE, the first Germanic king to hold the title. Until its end in the 19th century, the Empire would continue to be ruled by German nobility.

With the Salian and Hohenstaufen dynasties, however, the assumptions made through the cooperation of their predecessors began to be tested.

Ambitious Emperors like Henry IV and Barbarossa sought to redefine the primary source of divine right and entitlement, attempting to place religious authority into the hands of the Emperors themselves.

While their attempts at reform met with some success, the difficulty of maintaining the territories of Imperial rule, as well as the Papacy’s diplomatic and political acumen, would eventually see most of these Emperors capitulate and ultimately abdicate their claims to a sacred authority directly connected to God.

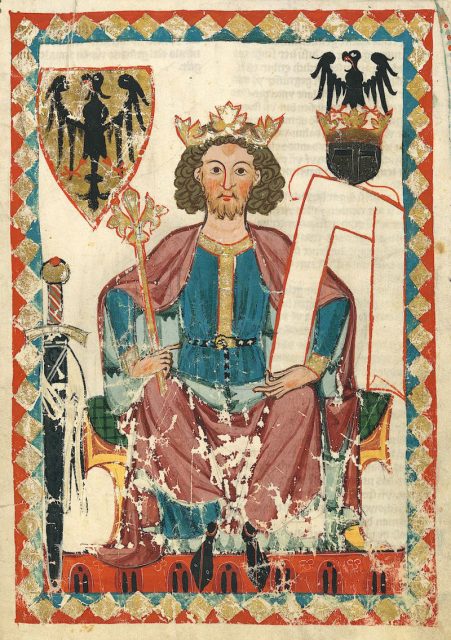

As part of the Hohenstaufen line, Frederick II’s life would be shaped by this strained relationship from the very beginning.

His father, Emperor Henry VI, had been trying to make the kingship of Germany hereditary, breaking from the traditional method of election held by the many princes and lords of the land. Historically, they had chosen the next king by vote.

While this method still resulted in dynastic rule, it reflected and protected the power held by the many Germanic lords over Imperial administration. Their next king was most likely going to become the next Emperor as well, so this system provided a consistent check on a centralized, monarchical state.

Henry VI’s proposal threatened to destabilize this balance between small and large government, so it was quickly shot down. Still, they would elect his son Frederick II to be king of Germany in 1196, even though he was only two years old.

The flaws of this complex government would become apparent after Henry VI’s untimely death. The regency of the Empire fell into the hands of his wife, Empress Constance, who would seek to strengthen the ties between Imperial territories before her son came of age and assumed power.

As the daughter of the Sicilian King Roger II, her marriage to Henry VI had guaranteed strong ties between the kingdom and the Empire. To cement this, Constance brought Fredrick II to the island to have him crowned King of Sicily in 1198CE. At four years old, he had obtained his second title.

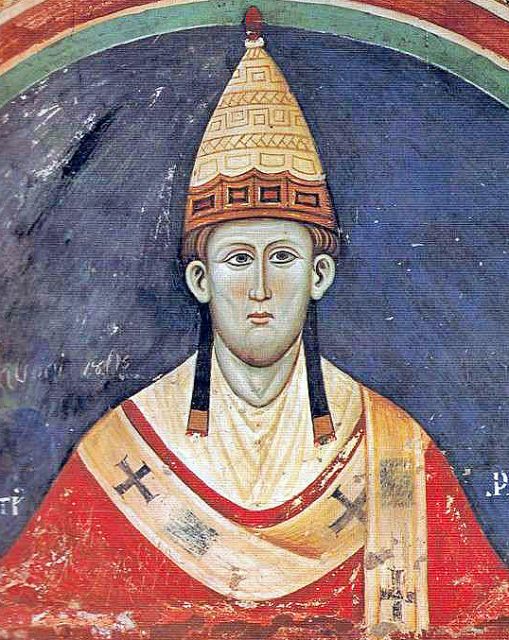

Her death in the same year threatened to fracture the Empire completely. She had placed Fredrick II and the regency of Sicily in the hands Pope Innocent III, hoping to form a more lasting relationship with the Papacy, but this tutelage under the church raised questions for the princes in Germany.

With a lack of centralized authority, political infighting began. Sicilian warlords used the power vacuum as an opportunity to expand their own power and prestige.Pope Innocent III became compelled to involve the church in Imperial politics and, in the process, reignited the tensions caused by the role of religions and authority in secular government.

The conditioning of Frederick II to be a useful Emperor to the Papacy was therefore very important. It was a chance to reassert the church’s authority by empowering a compliant and competent ruler in the spirit of Charlemagne and Otto I. Together they would be able to reestablish a more harmonious relationship, bringing the Imperial and Papal territories back into the fold by religious decree and military might.

This envisioned world would ideally lead to absolute Papal supremacy, guaranteeing the Pope’s right to bestow divine power as he saw fit. In turn, the Emperor would use his given titles to solidify his own authority over the many territories and people that made up his dominion.

When Fredrick II was crowned Emperor in 1220CE after a series of successful campaigns against his Sicilian and German enemies, the manifestation of this plan seemed within reach.

At his coronation as Emperor, Fredrick II had promised Pope Innocent III to fulfill his wish of leading a crusade to recapture Jerusalem. The previous Fourth and Fifth Crusades had been unsuccessful in achieving their intended objectives, failing to take Jerusalem and weakening Islamic power in the Holy Land.

This directive imposed upon the new Emperor had the dual purpose of immediately displaying his compliance and, in the event of success, exemplifying the righteous will and leadership of the Papacy.

Despite the prospects of the holy venture, Frederick II found the focus of his rule in Italy and Sicily. Much still needed to be done to quell the animosity towards Imperial rule south of the Alps. Powerful warlords and proud city-states continued to threaten his Empire, an all too familiar problem for which the previous Emperors had been unable to find an adequate solution.

For most of these Emperors, Italy had simply been a road to Rome, a pathway to Imperial title and divine legitimacy. However, they had consistently failed to endear themselves to the Italian people, often opting to remain in Germany and rule from afar.

Breaking from this tradition, Fredrick II would spend almost all of his reign in his Italian and Sicilian territories. As he established his control over the south, he began working on administrative and legal reforms to make a more efficient, prosperous, and united empire.

By 1227CE he was finally ready to embark for the Holy Land. Having settled many of his issues in Italy, he had reached an opportune moment to fulfill his vows to the Papacy.

But as he embarked from Brindisi, his army was decimated by a devastating epidemic that suddenly broke out aboard the ships. He was forced to turn back and delay his expedition once again.

Pope Gregory IX, fully aware of his previous promises, was unconvinced. The Emperor had already failed to join the Fifth Crusade called by his former tutor, Pope Honorius III. His reluctance then and now was seen as a convenient excuse to defy Papal authority. For these reasons, Fredrick II was excommunicated from the church for failing his obligations as its protector and servant.

But that following year he set sail for Jerusalem anyway. Even without the church’s support, he still managed to arrive at Acre, the Crusader capital, with around 12,000 soldiers and knights.

The issue of his excommunication, however, posed significant problems with the established Christian military orders of the Levant. Without the backing of the Pope, the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller were reluctant to serve.

Nonetheless, the Germanic order, the Teutonic Knights, joined with him. Many of the Templars and Hospitallers then followed under the pretext that they were supporting the crusade but not its leader.

He met with less success in relation to the Christian religious authority of Jerusalem, the Latin Patriarchate, but their refusal to support him failed to deter Fredrick II from marching to Jaffa in modern-day Israel in 1229CE.

There were more reasons for Fredrick II to take Jerusalem than mere pride and ambition. In 1225CE he had married Isabella II of Jerusalem, an arranged affair between the Emperor and the Papacy meant to expedite his crusade.

Through this marriage, the Emperor would have the claim he needed to declare himself King of Jerusalem. Isabella II was a descendant of a line of queens that had ruled Jerusalem. Through this new familial link, Fredrick II was entitled to the throne. She died in May 1228CE, however, giving birth to their son, Conrad, only a few months before the Emperor left for his crusade.

Even though his claim had been weakened by his wife’s death, the Sixth Crusade continued. From Jaffa, Fredrick II would attempt to display his army as an intimidating force prepared to do battle with the Sultan of Egypt, al-Kamil of the Ayyubid dynasty, by marching his troops down the coast and back.

Incidentally, the Islamic leader was not in a position to call the Emperor’s bluff. He was already embroiled in a bitter civil war with his brother, al-Mu’azzam. Having allied himself with the Turkish Khwarazmians, al-Mu’azzam had been destabilizing al-Kamil’s rule in modern-day Iraq for the past two years.

With both the Emperor and the Sultan having little to gain from conflict, they were eager to search for a diplomatic resolution and avoid what would inevitably be a brutal war.

Fredrick II’s multi-cultural background from his tutorship and administration in Sicily proved to be a boon in his dealings with al-Kamil. He spoke Arabic fluently, and his personal bodyguards included a host of Muslim soldiers. It is assumed the Emperor had a profound respect for the Islamic world, and his relationship with the Sultan seemed to exemplify a mutual level of understanding between the two rulers.

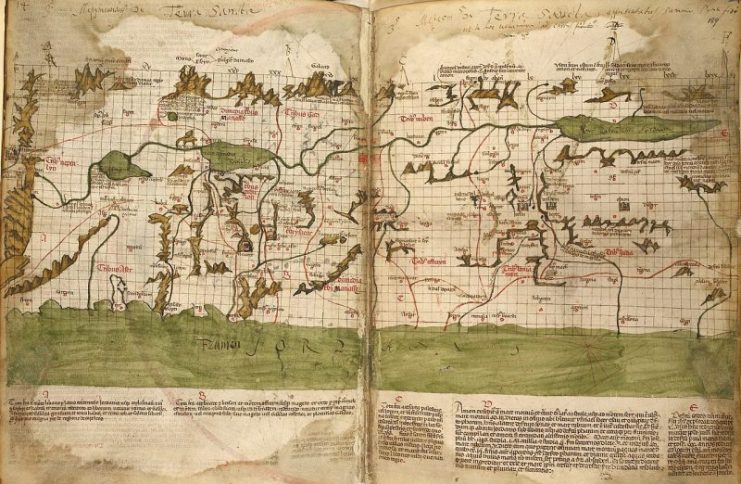

Al-Kamil had already negotiated a possible surrender of Jerusalem during the Fifth Crusade, and the recovery of the Holy Land could only boost Fredrick II’s popularity and prestige. Without a single battle, the Treaty of Jaffa and Tell Ajul was signed on February 18, 1229CE.

The Sixth Crusade, for all its intents and purposes, was a success.

In March, Fredrick II crowned himself King of Jerusalem in the Holy Sepulcher. Though unpopular with the locals, the official and legitimate acquisition of such an important title was a victory for the Emperor.

But his long absence from Italy was already beginning to form opportunities for his enemies (most notably Pope Gregory IX) to begin undermining his rule south of the Alps.

The Emperor would leave the Holy Land only a few months after his arrival in Jerusalem. Although he had secured Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem, as well as a strip of coastal land along the Levant, his swift departure largely left the Crusader States in disarray and disrepair.

In many ways, he had made their positions less defensible, and the confusion caused by his unsuccessful administrative reforms caused greater rifts between the competing powers of the land. By 1244CE the Khwarazmians, backed by the Ayyubids, would conquer Jerusalem and raze it to the ground.

While Fredrick II had made peace in the Holy Land, the Empire he returned to in Europe was at war. The Papacy had already begun taking advantage of his excommunication by fomenting insurrection amongst the warlords and nobility of Italy. Eventually, the Emperor was forced to relinquish some of his power in Sicily in return for the removal of his excommunication.

Much of the remainder of his reign would be spent fighting civil wars throughout the Empire, many of which would end in the gradual loss of the centralized power he had consistently struggled to maintain.

His legacy, like his life, has made Fredrick II a controversial figure in history. A man of extraordinary intellect and ambition, the intentions behind his often contentious actions remain a subject of debate.

In his time he was called both the “astonishment of the world” as well as the “predecessor of the Antichrist.” His diplomatic ability and passion for science, administration, and governance have resulted in many historians referring to him as the first modern European ruler.

While the Sixth Crusade could be considered a success, its role in the course of history is as complex and fascinating as its leader. Under his rule, the Holy Roman Empire would reach its largest limits, encompassing central Europe, Italy, Sicily, and the Holy Land.

Whether he was a man ahead of his time or a power-hungry opportunist, Fredrick II was a true example of the prestigious title he held. He was an Emperor.