In 1939, a German combat aircraft set a world speed record. The new Heinkel fighter appeared to be a fearsome addition to the Luftwaffe – technically advanced and faster than any other fighter then in service.

In the early stages of World War II, Allied pilots reported many encounters with the Heinkel 113. A Hurricane pilot claimed to have shot one down over Dunkirk in May 1940 and several were reported to have been attacked over Britain in August and September of the same year.

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, the commander of Royal Air Force (RAF) Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain, noted that the He 113 “made its appearance in limited numbers…its main attributes were high performance and ceiling.”

When the US Army Air Forces began flying bombing raids against targets in Germany, crews reported several encounters with the He 113 – “Very pretty plane!” noted one B-17 pilot who had been attacked by three of these aircraft over the French coast in 1942.

The thing that makes these encounters interesting is that the Heinkel 113 never existed. Prototypes of a new Heinkel fighter were built, but they never entered service with the Luftwaffe. The role of the Henkel 113 as a front-line fighter was a myth created by a very successful Nazi propaganda and deception campaign.

The story of the phantom super-fighter began in the mid 1930s with the design of the Heinkel 112, a sleek monoplane built in response to a Luftwaffe requirement for a new fighter capable of challenging the Supermarine Spitfire.

The Heinkel lost out to the Messerschmitt Bf 109 but around one hundred copies were built and sold to countries including Hungary and Romania.

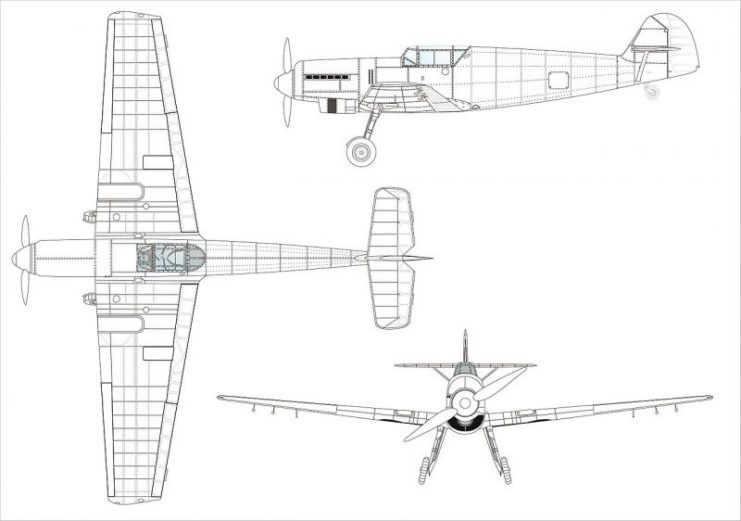

Soon after, Ernst Heinkel began work on a new and more advanced design, a “super pursuit fighter” which would offer a substantial performance advantage over the Bf 109. The result was a very fast monoplane fighter which used the same Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine as the Messerschmitt but was appreciably faster.

The Heinkel design focused on reducing drag in several areas. For example, the supercharger inlet for the DB 601, which was mounted on the side of the cowling on the Bf 109, was moved to the leading edge of the left wing.

The cooling radiators which were used on the Bf 109 were replaced by an innovative system which used cooling ducts in the leading edge of the wings to generate drag-free evaporative cooling.

The engine was mounted directly on to the front fuselage, negating the need for engine mounting spars and allowing a very slim, tight-fitting cowling. Even the exhausts incorporated ejectors which produced a little additional thrust.

The first prototype of the new aircraft was flown in January 1938. Although 113 was the next number available to Heinkel, the fighter was given the designation He 100, allegedly because Ernst Heinkel felt that pilots might be put off by an aircraft designation which included the unlucky number 13.

Twelve prototypes were built and it was quickly obvious that the new aircraft was very fast – a modified Heinkel 100 took the absolute world speed record with a widely publicized 463.919 mph (746.606 km/h) in March 1939. The performance of the new fighter was widely reported, though confusingly it was identified both as the He 100 and the He 112U (with the “U” standing for Udet).

Extended testing during the summer of 1939 confirmed that the Heinkel was notably faster than the Bf 109, but it was also found to have some substantial problems. The evaporative cooling system and its associated pumps proved to be troublesome in use and potentially vulnerable to combat damage, so it was replaced by more conventional system using a semi-retractable radiator below the wing.

Directional stability was found to be poor, and the tailfin was enlarged on some later prototypes. High wing loading meant very high landing speeds. The tight-fitting cowling proved awkward to remove and replace.

At some point during 1939, a decision was taken not to proceed with production of the Heinkel 100 and to focus instead on the Bf 109.

Partly this was a matter of the rationalization of scarce resources –there seemed little point in investing time and money on another single-seat fighter when the Bf 109 was proving to be a sound design and the Heinkel plant was already stretched to capacity by production of the He 111 bomber.

Partly however, this decision was also a result of the Byzantine complexity of the process of armament procurement in the Third Reich.

In 1933 Field Marshal Erhard Milch became the State Secretary of the Reich Ministry of Aviation (RLM) and assumed responsibility for re-arming the Luftwaffe. That was complicated by the fact that the abrasive and mercurial Milch had managed to fall out with a great many people in the German aviation industry.

He detested both Hugo Junkers and Willy Messerschmitt, two of Nazi Germany’s foremost aircraft designers, and spent considerable time unsuccessfully trying to block either from providing new aircraft to the Luftwaffe.

However, Milch reserved a special loathing for Ernst Heinkel. There is a suspicion that he intervened unofficially because of this personal animosity to ensure that the new Heinkel fighter never progressed beyond the prototype stage. That might have been the end of the Heinkel 100 story had it not been for the intervention of Joseph Goebbels’ Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.

In late 1939, the war had begun and the twelve prototype Heinkel 100s were still at the Heinkel works near Rostock in Northern Germany. These were painted with fictitious squadron markings and photographed with Heinkel technicians posing as pilots and ground crews. Some of the Heinkels were even repainted between photographs to give the impression that there were more than twelve aircraft.

The photographs were then published in Der Adler, the official Nazi magazine of the Luftwaffe, and were labelled as “Heinkel 113 fighters” which were said to have been photographed on a Danish airfield after seeing combat in Denmark and Norway. One of the aircraft was identified as a night-fighter variant.

It’s not entirely clear what the purpose of this propaganda was, but it certainly seemed to have impressed the RAF. The British Air Ministry included the Heinkel 113 on its recognition charts of German aircraft, noting a top speed of 390 mph.

A secret RAF intelligence report published in 1940 concluded that the new fighter was in production and that it equipped at least one front-line Luftwaffe squadron. In May 1940 a photograph of the He 113 appeared in The Aeroplane, a respected British aviation magazine, where it was identified as a current German fighter.

However, not everyone was convinced. Robert Saundby, the Senior Air Staff Officer at RAF Bomber Command, noted in a memo that in the photographs it was clear that the Heinkel 113 had no space in the wings for guns or ammunition, an odd omission for a fighter!

Another eagle-eyed RAF officer noted that the night-fighter version lacked even a landing light. Despite these obvious issues, the perception that the He 113 was a front-line Luftwaffe fighter persisted for most of the war.

Read another story from us: The Owl-Eagle – 14 Facts About the Heinkel He219 Night Fighter

No Heinkel 100/113 was ever used operationally but Allied pilots continued to report encounters with this aircraft throughout the war. It is assumed that most were simply misidentifications of later models of the Bf 109, but it was only when the war ended that the Nazi Super Fighter was finally confirmed to have been no more than a propaganda myth.