For sixty years, the highest mountain hotel of the USSR and Russia was located on the southeast slope of Mount Elbrus at an altitude of 2.5 miles above sea level. The hotel successfully remained intact throughout World War II despite being captured and then repeatedly defended by the Germans against the Soviets.

After the war it stood abandoned until 1957, and then received tourists until the tragic events of August 16, 1998. Due to violations of fire safety rules on that day, the building was destroyed by fire.

In 1909, a group of eleven tourists from the Caucasian Mining Society made a trip to Elbrus. Enthusiast Rudolf Leizinger headed and organized the campaign. While there, the group built a temporary camp in the area of the rock ridge.

At the place of the temporary camp, the group painted the inscription “Shelter 11” on the stones. None of the participants in the campaign suspected that their playful inscription on the stones would later be symbolic and memorable in the history of the Caucasus climbing movement.

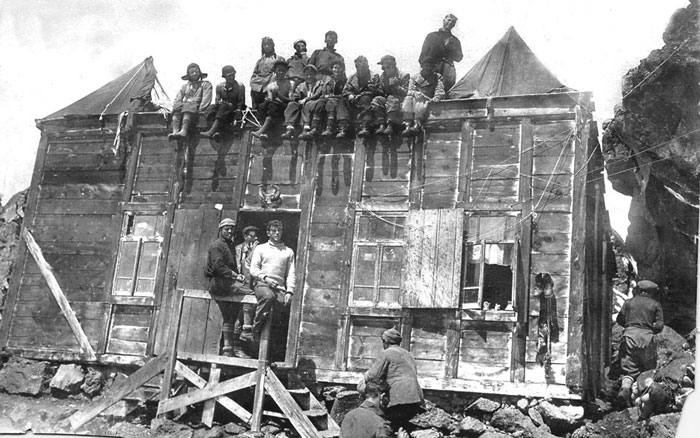

Twenty years later, in the summer of 1929, the famous Soviet mountaineer Rakovsky built a wooden hut reinforced with iron on that spot and wrote the same inscription on it: “Shelter 11.” It was a spacious building capable of holding forty people. However, this was not large enough, as there were many climbers on the route.

Soon, on the site of the Rakovsky hut, a new larger building with the name Shelter 11 was built. The project manager of the three-story alpine hotel was the engineer and builder of the first Soviet airships, design and mountaineer Nikolay Popov. The new building was built a little higher than the old hut and could accommodate more than 100 people at a time.

The construction of the hotel began in the spring of 1938, and by the autumn of 1938 the residential building, boiler room, and diesel station were mostly built. Bridges were made between the “Ice Base,” the place where the road to Elbrus ended, and the old Shelter 11 hut. They passed through the glacial cracks, and allowed caravans loaded with construction materials to cross.

The hotel building was shaped like a dirigible. The upper part was rounded and was thus able to withstand the effects of strong winds and storms. For waterproofing, the walls of the hotel were covered with galvanized iron sheets. The main building had 3 floors: the first floor consisted of stone, the second and third of wood.

For insulation, there were special heat-insulating plates around the entire perimeter of the building. Work on the interior continued through the winter, until all work had to be stopped due to the extreme cold. In 1939 work was resumed, and in the autumn the hotel received its first visitors.

For about sixty years, Shelter 11 had the status of the highest mountain hotel in Europe. On the ground floor, there were shower rooms, storage rooms, and a kitchen. On the second and third floors were residential premises, equipped with wagon type bunk beds. The rooms also had special chests for storage of equipment and personal belongings.

The ceilings and walls of the hotel were lined with linkrust, a building material with a washable smooth or embossed surface, and the floors were made of varnished parquet. The building had running water, sewage and central heating.

On the second floor, the dining room could accommodate fifty people. Some experts compared the hotel with comfortable first class hotels. Once, a visitor called it “Hotel above the Clouds,” after which other visitors began to use this name.

On August 17, 1942, German mountain troops penetrated the Elbrus region through the Hotutau Pass and, under the command of Captain Grotte, captured Shelter 11 without a single shot.

According to the Soviet version of the story, at the time of the seizure only the head of the meteorological service, his wife, and a meteorologist were in the hotel. They had continued to work, as they had received no information about the approach of enemy troops.

On the same day, three Soviet intelligence officers had come into the area from their base in the Baksan gorge. They observed the movement of the German huntsmen and, given the inequality of power, decided not to engage in battle with them. The scouts decided to go back to the gorge, taking with them the valuable meteorological equipment.

The presence of thick clouds and the decision to bypass the “Old Horizon” station allowed the Soviet intelligence officers to quietly descend into the Azau glade and avoid the Germans.

However, according to the German unconfirmed version, approximately forty-five “Kyrgyz Arrows” and Russian commanders guarded Shelter 11. A German commander named Grotte, with a white handkerchief in his hands, climbed up to them and persuaded the Soviets to surrender. Either way, despite the inconsistency of the versions, the Germans did capture Shelter 11 without a single shot.

After the capture of the hotel, the German huntsmen climbed Mount Elbrus and installed Nazi flags there. German propaganda used these events to claim a victory in the Caucasus. However, in fact it was different. Most of the mountain passes were guarded by Soviet troops, who did not let the enemy pass to the Black Sea.

The Soviet troops repeatedly tried to regain control of the Shelter 11 hotel. Due to weather conditions and fortified positions, the Germans managed to repel the Soviet attacks. In these battles, the Red Army lost about 100 soldiers.

Shortly after the defeat of the German troops in the battle of Stalingrad, the situation in the Caucasus changed. Because of the threat of encirclement, the Germans were forced to abandon their positions in the Caucasus. On January 10-11, 1943, the German mountain units left the Baksan gorges and Shelter 11.

On February 9, 1943, a group of twenty Soviet climbers who fought in the Caucasus regained control of Hotel Shelter 11. Their main task was to remove the Nazi banners from the peaks of Elbrus. The hotel building was riddled with bullets and bomb fragments, and an explosion had destroyed the roof of the diesel station. This was a sign of air strikes.

The meteorological station had been completely destroyed by the German soldiers, and abandoned ammunition and warped weapons lay all around. All food warehouses were deliberately flooded with kerosene or destroyed.

In the postwar period, in 1949, the USSR Academy of Sciences leased Shelter 11 for five years. In the same year, the road to the hotel was restored and work began on restoring the Ice Base and Hotel buildings. Significant funds and human resources were spent to restore buildings and communications.

In 1950, many buildings were restored, including intermediate ones. About two tons of various building materials were used in the work. In the autumn of 1951, a special high-voltage wire was carried from the village of Terskol to the hotel. However, the following year, the electric line was destroyed due to the winter movement of the glacier.

During all the years after the war, Shelter 11 served as a resting place for many climbers who made the ascent to Elbrus. Thanks to the efforts of enthusiasts, a museum was created on the third floor of the hotel.

Read another story from us: German Mass Grave Discovered in Stalingrad

On August 16, 1998, the main building of Shelter 11 burned down due to violations of fire safety regulations. Presumably, a tourist from the Czech Republic or Russian guides can be considered guilty of this. Currently, the old burned-out building is almost dismantled, and the former diesel station was converted to hold 50-70 people. In addition, about twenty residential trailers were placed around the diesel station building.

A new hotel, LEAPrus 3912, was opened in September 2013 a few hundred meters from Shelter 11. It consists of four modular structures made in Italy and delivered to Russia.