Countless heroic tales have gone unrecognized from periods of warfare that have formed parts of American history. For several years, many heroes were overlooked during considerations regarding the Medal of Honor, with, unfortunately, one of the main reasons against its presentation being race.

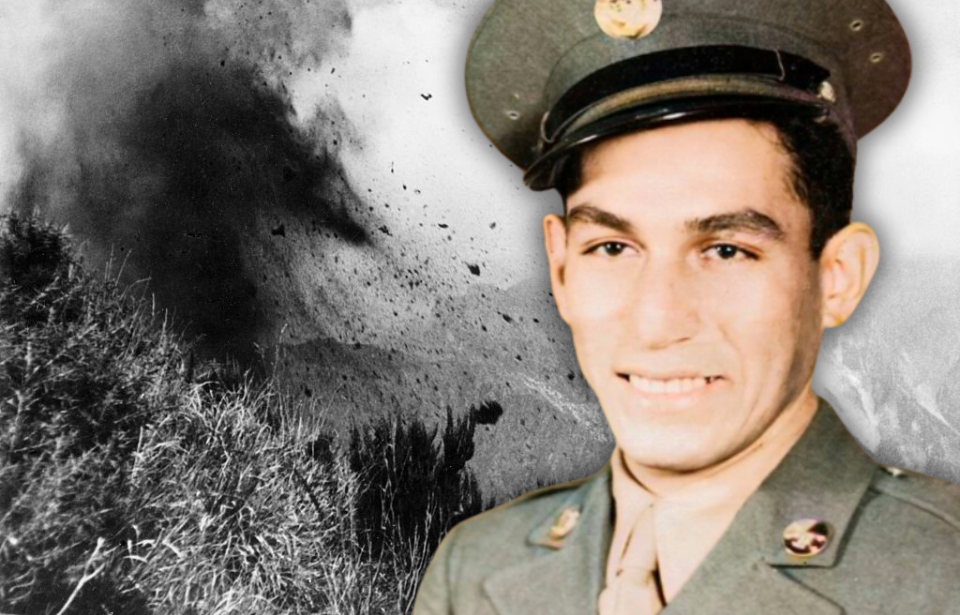

On the afternoon of March 18, 2014, some of these wrongs from the past were finally righted, when 24 US Army veterans received the military’s highest honor. Among those recognized for his bravery was Master Sgt. Manuel V. Mendoza.

Mendoza was 20 years old when he was drafted into the US Army in November 1942. Four months after D-Day, the then-staff sergeant single-handedly halted a fierce German counterattack in a largely overlooked event of the Second World War.

Breaking through the Gothic Line

After a horrific battle, the 88th Infantry Division broke through the heavily fortified Gothic Line, during their northward advance through Italy. Elements of the 350th Infantry Regiment then proceeded to occupy Monte Battaglia, which, surprisingly, had been left unmanned by the enemy.

The mountain was a very important area. At 2,346 feet, it towered over the surrounding highlands, making it a valuable position for whoever occupied it. Why the Germans left it unguarded was unknown. However, after the Americans took up their positions, the enemy launched an aggressive counteroffensive.

They let loose a hellish rain of fire on the 350th, as they desperately fought to take back the mountain. In the chaos, almost half of the regiment became casualties.

Manuel V. Mendoza jumps into action

On October 4, 1944, a heavy barrage of German mortars struck the mountainside. It was a clash of determination: the Americans threw all they had to stop the enemy from taking the position, and the Germans, likewise, hit as hard as they could in a valiant bid to reclaim the important landmark they’d erroneously left unguarded.

As the casualties piled up, Manuel Mendoza, who was, by then, a platoon sergeant with B Company, got shot in the arm and leg. Maybe the resulting pain fueled his fury or maybe it was all just mindless bravery, but the soldier, paying little or no mind to his wounds, took up a Thompson submachine gun and raced to the top of the hill.

From the crest, he saw hundreds of enemy soldiers surging up the slopes, armed with machine pistols, rifles, hand grenades and flamethrowers. Seeing this, Mendoza engaged them in a fierce firefight, spraying bullets down the slope. He emptied around five clips, hitting 10 men.

When his ammunition ran out, Mendoza dropped the submachine gun, grabbed a carbine and resumed his fight with the enemy. Again, he ran out of ammunition. Somehow, a single German soldier came within a few yards of the crest, wielding a flamethrower. Seeing Mendoza had run out of bullets, he rushed to eliminate the one-man squad, but the staff sergeant snatched his pistol and was able to take the man down before he could fire the flamethrower.

Not willing to back down from a fight

The enemy forces continued up the ridge, determined to take it back. Spotting an abandoned machine gun emplacement, Manuel Mendoza jumped into it. Another hail of bullets began, which the Germans were forced to dodge.

Seeing the emplacement didn’t cover the entire advancing force, Mendoza lifted the machine gun off the ground and went mobile with it, holding it at hip level. The oncoming troops were served with an ear-splitting rattle of bullets. They scattered in different directions, giving Mendoza the opportunity to set the gun down and continue his deadly assault until it jammed.

The Germans may have heaved a short sigh as they heard that last click, hoping it was over and they could resume their advance – but the worst had been saved for last.

Manuel Mendoza single-handedly took out 30 enemy soldiers

As soon as the machine gun had jammed, Manuel Mendoza grabbed several hand grenades and began hurling them at the enemy. This was more than the Germans could take, and they began a hurried retreat. After the counterattack had ceased, the staff sergeant ran down the slope and captured one wounded soldier. He also retrieved several weapons left behind by the Germans as they scampered for safety.

Having secured the ridge, Mendoza moved on with his comrades to help consolidate the Americans’ positions. After the dramatic engagement between him and the enemy, 30 soldiers were dead. However, his heroism was acknowledged with the Distinguished Service Cross, rather than the Medal of Honor.

Manuel Mendoza finally received the Medal of Honor

After World War II, Manuel Mendoza continued his service with the US Army and was wounded during the Korean War. He left the service in 1953 and went to work at Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station until retirement. He died in 2001, at the age of 79.

Following a review of Distinguished Service Crosses awarded to Hispanic Americans and Jewish Americans during the conflict, Mendoza’s actions were finally properly recognized. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by then-US President Barack Obama.

More from us: HMS Glowworm (H92) vs Admiral Hipper: A Daring Battle in the North Sea

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

The decoration was accepted by his wife, Alice Mendoza, on March 18, 2014.