On the night of the 19th of February 1945, Allied forces in Burma were allegedly aided in their efforts by a group of reptiles which decimated over 90% of their enemy.

This story has gained increasing credence in recent years. However, those with a more investigative eye cannot help but be skeptical of this bizarre tale from history.

The story comes from the writings of Bruce Stanley Wright, a British naturalist who was presumed to be at the scene. It is mentioned in his 1962 book Wildlife Sketches: Near and Far.

However, the veracity of the crocodile aggression has gradually grown throughout the years, despite there being no other references to it within historical writings relating to the Far Eastern theatre in WWII.

The passage in Wright’s book outlining the supposed crocodile massacre states as follows:

“That night was the most horrible that any member of the M. L. [motor launch] crews ever experienced. The scattered rifle shots in the pitch black swamp punctured by the screams of wounded men crushed in the jaws of huge reptiles, and the blurred worrying sound of spinning crocodiles made a cacophony of hell that has rarely been duplicated on earth… Of about one thousand Japanese soldiers that entered the swamps of Ramree, only about twenty were found alive.”

It is undoubtedly a gripping tale, so it’s not surprising that this account has motivated a swathe of articles. The incident was even included in the Guinness Book of World Records in 1968 under “worst crocodile disaster in the world” as well as “most fatalities in a crocodile attack” (despite there being not a single death officially recorded).

However, we must ask the question: did this event really occur?

Of course, the threat posed by saltwater crocodiles was an ever-present one in the Far Eastern theatre of World War Two. This was particularly so in the mangrove swamps where such reptiles thrive, like on Ramree Island.

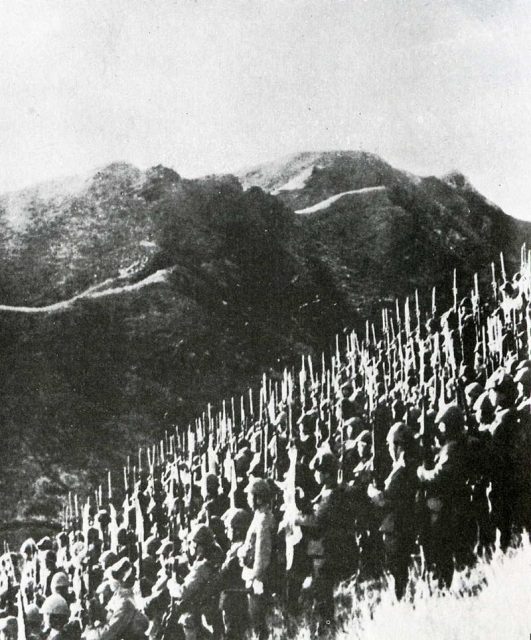

But are we really to believe that a sizable force of trained Japanese soldiers was decimated by an onslaught of crocodiles? After all, these were soldiers who had offered up stubborn resistance to the British Fourteenth Army under the leadership of Lieutenant General William Slim.

The current evidence, which is clear but limited, suggest we should not believe it.

For example, the British official history (War against Japan Volume IV: The Reconquest of Burma, 1965 (2004)) serves as the main source in the study of the Fourteenth Army’s attempt to drive the overstretched Japanese from Burma beginning in the late summer of 1944.

In this official account there are references to the menace posed by saltwater crocodiles at Ramree Island. However, there is no specific mention of the crocodile attack devouring over 900 Japanese.

In addition, the references made to crocodiles are minimal compared to the passages detailing the dangers of malaria. This disease seriously hindered both sides’ attempt to gain control of the island. On mainland Burma, diseases such as malaria accounted for almost half the total death toll of Allied forces.

Furthermore, this official account which contains no mention of the massacre, nevertheless emphasizes the fierce Japanese resistance which lasted into April 1945. This suggests that the Japanese did not suffer a major setback of over 900 men finished off on the night of February 19th.

Frank McLynn, a prominent British historian on the Burma campaign, effectively denounces the crocodile aggression account in his thorough analysis of the Allied effort to retake Burma from the Japanese, The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph 1942-1945 (2011).

McLynn is disturbed by the willingness of other writers to cite the details provided by Wright and the Guinness Book of Records without confirming the veracity of such information. To counter this, he tries to provide a rational argument and bring a voice of reason to the debate.

For a start, he points out the lack of evidence for Wright’s claim that he was at the scene. McLynn also questions the likelihood of over 900 Japanese troops being killed overnight despite possessing an effective means of defense.

It is difficult to counter any of the reasonable arguments put forward by McLynn as there is simply no evidence to the contrary. No evidence, that is, unless one believes a solitary account by a mysterious character.

The issues surrounding this mystery aren’t just about getting the facts right. More importantly, focussing on such a wholly ungrounded event underplays the courageous role played by the Fourteenth Army in what was one of the most brutal theatres of the Second World War.

Read another story from us: The Soldier Who Went On A Suicide Mission Against The Japanese & Won

In Burma, the Allies faced a fierce enemy not only adept in jungle warfare and but also notorious for their suicidal kamikaze charges. The Allies also had to deal with challenges posed by logistics and supply problems, as well as malaria, cholera, and various other diseases.

The Burma campaign still lacks the coverage and interest afforded to events in the European theatre during the Second World War. We do not need to add mythical tales when reality provides a drama played out in all its honor and tragedy.