Divers faced grave dangers of fouling in wrecks, having their suits blown up by excess air or torn by wreckage.

The submarine USS S-4 (SS-109) lay stricken off the hook of Provincetown, Cape Cod. The boat, which had collided with the Coast Guard vessel Paulding, was now helpless on the bottom, with 40 men trapped in the boat. It was December 17, 1927, and the submariners were running out of time.

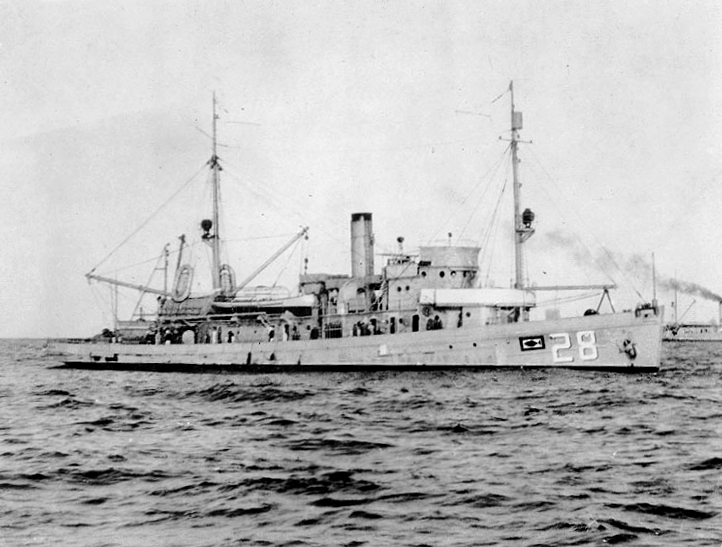

The Navy sent all its available resources to the scene, but the most important one was the salvage ship Falcon. Aboard the ship was all the gear needed to effect a rescue: compressed air generators, salvage pontoons, winches, and U.S. Navy divers. And of these elite divers the best one was Tom Eadie.

Tom Eadie was born in Scotland in 1887 as the third son of a stonemason. While he was still a child, the family immigrated to the United States, eventually settling in New Jersey. Eadie had good mechanical abilities but felt that he needed more to his life. So in 1905 he impulsively enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

He shipped as a seaman, took part in Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, and had minor disciplinary infractions. His service life was unremarkable until he was assigned to the naval base at Newport, Rhode Island where he was introduced to diving and thus found his calling.

Eadie became a master at the art of diving in the cumbersome hard hat rigs of the early 20th century. Connected physically to a diving vessel by a lifeline and airhose, divers faced grave dangers of fouling in wrecks, having their suits blown up by excess air or torn by wreckage, and contracting decompression sickness (the bends), all while working in a canvas suit with weights attached to stabilize the diver. The amount of weight and gear a diver might carry was upward of 200 pounds.

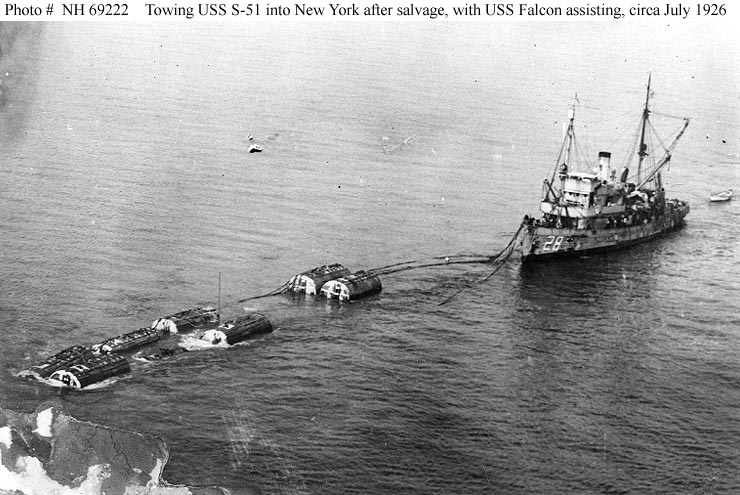

Eadie loved the underwater experience, and he eventually became a trainer. He became instrumental in several marine salvages, and received a Navy Cross for his work on the raising of the submarine S-51 which had sunk near Block Island on September 25, 1925.

Now Eadie was needed to help rescue the submariners of S-4. He was the first diver to go down to reconnoiter the wreck. Descending down a grapnel line attached to the sub, Eadie spun 102 feet to the bottom, landing on the wreck.

He found that the boat had been pierced in its battery compartment, but more importantly, the clunk of his heavy leaden boots brought the clang of noises from inside the wreck. Upon further inspection, Eadie found that there were men still alive in the forward torpedo room (it was later discovered to be one officer and five enlisted men), but he could detect no sign of life aft.

Reassuring the trapped men with a few taps of his hammer, Eadie ascended to the surface. The commanding officers of the rescue, Rear Admiral Frank Brumby and Captain Ernest King, considered the situation and decided that any men aft of the torpedo room had likely passed out from lack of oxygen. They figured that if they could raise S-4 quickly, they could revive the men.

The most expeditious way to raise S-4 was to blow its ballast tanks through a valve near the conning tower. A second diver, Bill Carr, was sent down and quickly made the connection with an air hose. He surfaced, and air from Falcon was blown through the hose and into the submarine. However, within an hour it became apparent that was not going to work – S-4’s ballast tanks were compromised.

The rescue team then decided that the only thing they could do was to try to get air to the men they knew were alive in the torpedo room since any other effort to raise the submarine would take weeks of work through the use of salvage pontoons. To deliver the air, there was a second valve near the conning tower that could theoretically do the job.

In the meantime, the sea kicked up and the wind started to gust at upwards of 50 miles per hour. A storm had come in. Falcon struggled at its moorings. It was the worst of possible diving conditions since the rocking and rolling of the ship would tug and yank at the divers’ lines. But they had to try.

Diver Fred Michels volunteered to go down to make the connection. He had a terrible time of it. When he descended he found himself over his head in mud. Falcon‘s crew heaved his lines and pulled him out.

When he reached the wreck, he found the valve, but his lifeline and air hose became fouled into the wreck. Since the swell of the sea required Falcon to pay out more line to Michels, all that excess wove itself as a net through S-4. Michels became trapped and soon his suit got cut in the wreckage. Freezing water entered the diving suit. Michels, who had been in the water for over an hour, pleaded through his telephone connection to the surface for help.

Lieutenant Hartley went to Tom Eadie who was recovering from his earlier dive in his bunk. Eadie volunteered to go even though conditions were worsening. When Eadie descended, he found Michels prone by S-4’s conning tower and nearly unconscious. All about him was a tangle of lifeline and air hose. There was no way he could get it loose by hand.

Eadie asked for, and received, a hacksaw which was sent down on a shackle via his lifeline. Most hands aboard Falcon figured Michels, and maybe Eadie, were as good as dead.

Eadie set to work, sawing and hammering at an angle iron that had caught Michels’ lines. During this process, Eadie’s suit became cut and water filled his suit up to the neck.

When he at last got Michels free, he found him so delirious that the stricken diver mishandled the valves on his suit, resulting in it filling with air and blowing him up uncontrolled to the surface. Eadie’s fear was that Michels’s would strike the bottom of Falcon, rupture his diving dress, and then the weight of the diving suit would sink and drown him.

Eadie surfaced, but luckily found Michels bobbing at the surface, and helped Falcon‘s crew bring him aboard. Both were placed into a large recompression chamber where compressed air was delivered to cure the bends which Michels and Eadie certainly had.

But decompression sickness was the least of Michels’ worries. He was hypothermic and described by Eadie as stiff as a “cold-storage bird.” He was unconcious and it took multiple men to move his joints. For hours, Eadie and his fellow divers massaged Michels, used linaments, and even slapped him about to get the blood moving.

At last, in the early hours of December 19, Michels revived. But he was terribly weak. Eadie’s rescue of Michels took almost two hours, so Michels had been on the bottom for three. Standard dives of the day did not usually exceed forty minutes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ACx2BxKyGA8

Michels had to go to a hospital. With the storm still ongoing, no more diving could be done. Falcon weighed anchors and headed to Boston.

Meanwhile, other ships stood vigil over S-4. Communication was established with the submariners through the use of Morse code. The submariners’ most plaintive question: “Is there any hope?” Captain King composed the reply: “There is hope. Everything possible is being done.”

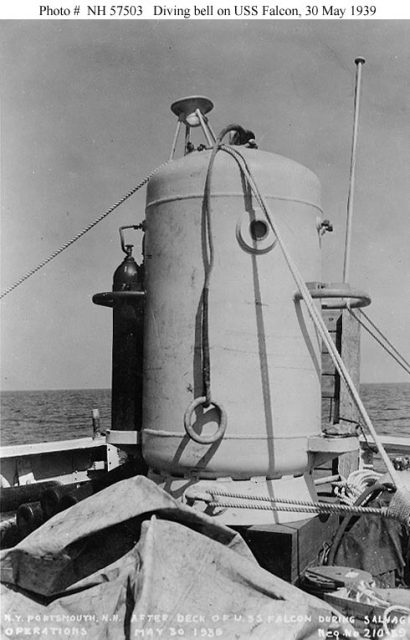

Falcon returned to the scene but still the storm raged. It was only on December 21 that the weather moderated. When the divers went down, and despite a successful effort to get oxygen into the torpedo room, they confirmed that all the men aboard S-4 had expired. But their sacrifice was not in vain since the uproar over the disaster led directly to improvements in submarine rescue technology, such as the Momsen Lung and the McCann Rescue Chamber.

Tom Eadie was awarded the Medal of Honor. When President Calvin Coolidge presented it to him on February 23, 1928, Tom Eadie said, “I want to assure you, Mr. President, that everything humanly possible has been done on that job, under the circumstances.”

Read another story from us: Tragically Unlucky – The Sad Tale of the USS Sculpin

The Navy went on to carry out the salvage of S-4 in a winter operation, the first of its kind, in which Eadie earned another Navy Cross for his work. He retired from the Navy in 1939, but came out of retirement when the United States entered World War II.

He was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal. The Navy commissioned him as a lieutenant, and he retired again in 1946, returning to private life and fading from the historical record. He passed away in Brockton, Massachusetts in 1974.