That the world needs the threat of nuclear warfare to maintain a semblance of peace is a contradictory reality most people have come to accept.

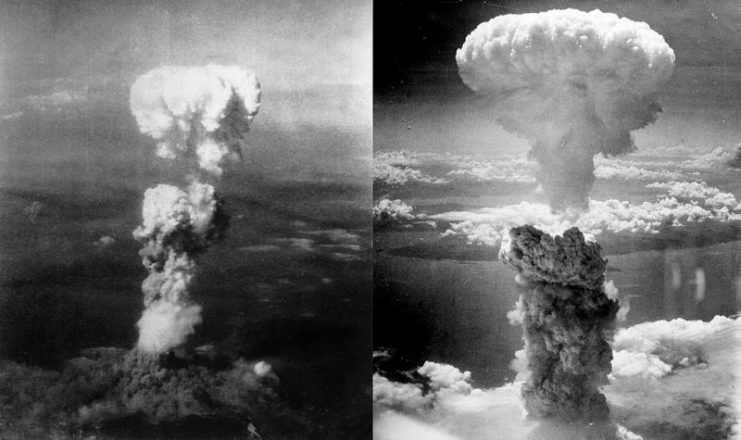

When America dropped the bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in Japan at the end of World War II, it briefly seemed that the world understood that these weapons only led to untold destruction in a manner mankind might never recover from.

But shortly thereafter, other nations hurriedly joined the nuclear race by developing their own bombs with the aim of building ones even more powerful than those dropped on Japan.

One country that is, and has been for decades, a keen rival of the United States in many ways but particularly in military technology, is Russia.

Political legend has it that Nikita Khrushchev, in 1960, used the expression “Kuzma’s mother,” while speaking to the United Nations (UN) General Assembly about nuclear weapons. It is a slang expression that means, roughly, “We’ll show you.”

Indeed, the Soviets had a clear point to make, aimed specifically at the United States. In 1961, it made good on that promise.

When Russia tested its first, massive nuclear bomb, known variously as “Tsar Bomba,” “Big Ivan,” “Kuzma’s Mother,” or “Joe III” (by the CIA), it was still called the USSR. The bomb was tested on October 31, 1961, at the cape of Severny Island. Its strength was approximately 1,500 times that of both bombs dropped on Japan.

The Tsar Bomba is the only one of its size and strength – 50 megatons of TNT – ever detonated. It had a massive “mushroom cloud” (as the byproduct of a nuclear bomb is known) that some experts say would have been visible 40 miles (64 kilometers) away.

The explosion supposedly shattered glass windows in Finland, more than 500 miles (over 804 kilometers) from its detonation site. It ruined everything within a radius of up to 30 miles (48 kilometers).

One problem the Russians faced – besides the potential for massive damage – was how to deliver and detonate such a huge bomb. It weighed about 60,000 pounds (over 27,000 kilograms), was 26 feet (almost eight meters) long and about seven feet (two meters) wide at one point.

How could a “standard” jet fly it into place, then get out of its reach? And more importantly, how would the pilots who flew that plane get out alive?

The answer was they wouldn’t, at least not definitely. The aircraft used had to be a one-of-a-kind design just to handle the Tsar Bomba.

So the Russians modified a TU 95 by taking off its bomb doors and its fuel tanks. The pilots and crew were given a 50/50 chance of surviving the delivery and test.

Engineers also attached a parachute of sorts to the bomb to slow down the speed at which it fell. This feature gave the plane time to escape the worst effects of the blast, but nonetheless the aircraft fell about 3,000 feet (over 914 meters) when the bomb detonated.

The pilot and crew got approximately 26 miles (almost 42 miles) away before the Tsar Bomba went off.

It was detonated “mid-air” rather than on impact with the ground, to help lessen its effects. The area was, of course, geographically barren. But in spite of such precautions, it had a profound effect on the land over which it was detonated, north of the Arctic Circle.

There were no reports of injuries or deaths reported in the Western media. It could have been much, much worse.

The bomb was capable of exploding with a capacity of 100 megatons, but officials knew the results were completely unpredictable, and the pilots would not have survived. Hence, they opted for the “smaller” version.

Casings were made for more of these bombs and are on display at two museums in Russia: the Russian Nuclear Weapons Museum near Sarov, and the All Russian Research Institute of Technical Physics in Snezhinsk.

Read another story from us: The Soviet Bomber Arsenal in Photos

Russia got what Khrushchev boasted of to the UN that day almost 60 years ago. That political and military leaders around the globe have chosen not to test another bomb, or an even bigger one, is something to be thankful for.

Given the unstable geopolitical situations we face today, it’s impossible to know for certain whether governments will continue to choose the safer, saner option.