The Americans and Australians were continuously plagued with small scale surprise attacks by the Viet Cong as they advanced deep into the woods.

When the Vietnam War began on 1 November 1955, the United States’ involvement was a relatively low-key affair. But the passing years would see increasing actions by the US as its military personnel on Vietnam soil gradually grew into thousands.

Starting out with just under a thousand military advisors in 1959, the number of US troops in Vietnam skyrocketed to over 180,000 following the 1964 hostile engagement between the United States and North Vietnam in the Gulf of Tonkin. By 1966, the US had gotten neck deep into the Vietnam War and was freely deploying ground combat troops into Vietnamese territory.

In a bid to cripple Viet Cong military forces in Saigon, the United States military, in collaboration with the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), sought to break all Viet Cong activities at their source. Several intelligence reports pointed to the presence of a key Viet Cong headquarters in a large underground bunker within the Ho Bo woods, about 2.5 miles west of the Iron Triangle and around 12 miles north of Cu Chi, Binh Duong Province.

Although its precise location remained uncertain, all Viet Cong activity in and around Saigon was believed to be controlled from this particular political-military headquarters. Operation Crimp was therefore generated as a search-and-destroy operation to eliminate it.

Featured in this operation were units from the US 3rd Infantry Brigade, the 173rd Airborne and the 1st Infantry Division, along with the 1st Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) which had two companies from the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment integrated into it.

An intense bombardment of the target region preceded the operation with the aim of neutralizing the strong defensive positions suspected to be guarding the headquarters. On the extremely cold morning of January 8, over 8,000 US and ANZAC troops were inserted on the north, west, and south of the woods. Operation Crimp had begun.

While the joint force combed the location, little of importance was found. The position of the headquarters could not be confirmed. On top of this, the Americans and Australians were continuously plagued with small scale surprise attacks by the Viet Cong as they advanced deep into the woods.

The Viet Cong units appeared from different positions, infiltrating the units at will and causing a number of casualties. While the US and ANZAC troops defended against these surprise attacks, they were bemused by the system of attacks these hostile units employed: suddenly appearing and then disappearing just as quickly as they came.

They soon realized, from their various locations around Cu Chi, that the Viet Cong were making use of a massive network of tunnels in this region to spring ambushes on them. As a matter of fact, the US and Australian units had been practically walking above the Viet Cong.

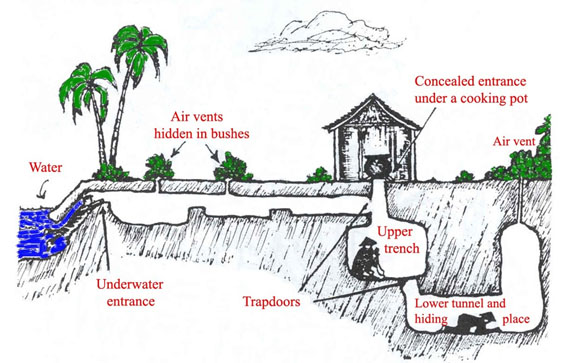

Originally created during the First Indochina War which had pitted the Viet Minh against the French, this extensive network of tunnels grew from a fairly basic system to a highly complex underground labyrinth in the 1960s.

By the time of Operation Crimp, these tunnel complexes included hospitals, storage facilities, barracks, training areas, and the Viet Cong headquarters, running from Saigon down to the Cambodian border. This network of tunnels was so extensive that it was believed by some to be capable of holding up to 5,000 men for several months.

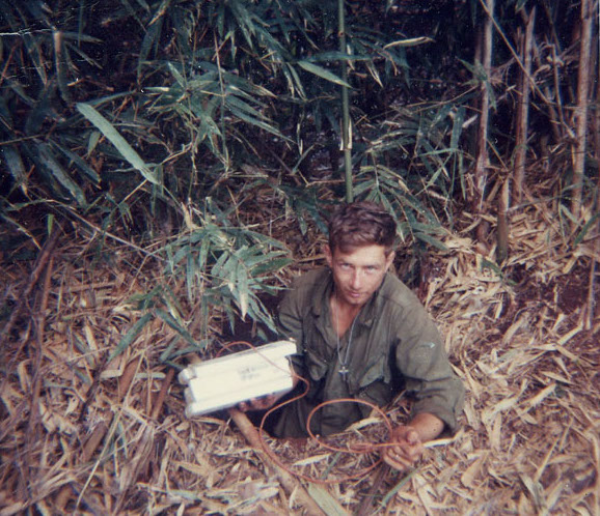

Thus, upon realizing the existence of these tunnel complexes, the mission objective shifted to finding, clearing, and destroying them.

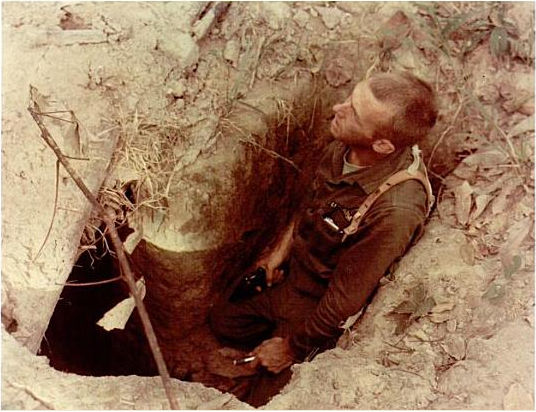

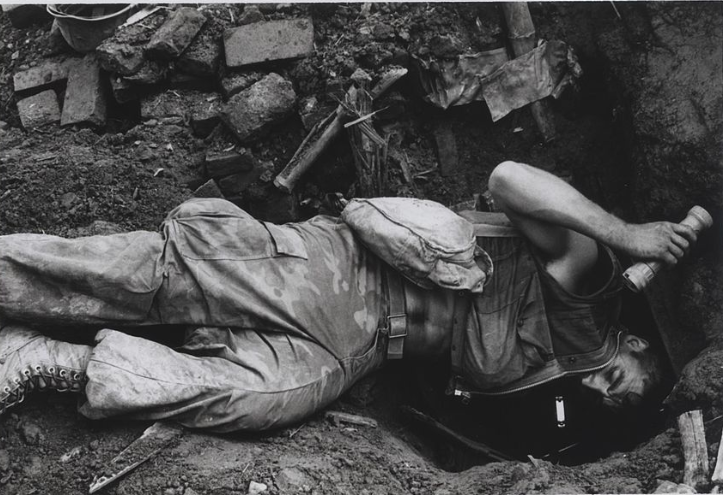

But venturing into these tunnels was not something everyone could do. They were barely large enough to contain a 5’6” man, and it needed an extra bit of courage to venture into these holes knowing that the chances of coming out alive were slim.

But among the many men of the joint American and Australian units, there were men who were equal to the task. They were called Tunnel Rats—an unofficial designation for the volunteer combat engineers and infantrymen from the United States, Australia, and New Zealand who ventured into the labyrinth.

They were armed with M1911 or M1917 pistols, along with bayonets, flashlights, and explosives, and charged with infiltrating these tunnel complexes and neutralizing any hostile occupants while gathering information along the way.

The Tunnel Rats faced a number of difficulties during these perilous missions. The tunnels were often booby-trapped with mines, hand grenades, and punji sticks. Poisonous snakes and scorpions lurked in some, and rats, spiders, ants, and bats were determined to make the job even more difficult.

The standard pistol was woefully unfit for this mission because the loud blasts from the muzzle were amplified by the walls of the tunnels and would deafen the Tunnel Rats momentarily after each shot. They had to opt for other kinds of pistols which were of far less quality than the standard pistol. Some of them preferred their personal weapons such as .25 caliber automatic pistols and sawn-off shotguns.

Sometimes while on the mission, a Tunnel Rat would meet a Viet Cong soldier, and would then have to engage in exceedingly close combat.

Several of these tunnels had sharp U-bends which could be easily flooded to trap and drown intruders. Also, poison gases were used by the Viet Cong against intruders in the tunnels, prompting some Tunnel Rats to go in with gas masks. However, gas masks made it harder to hear, see and breathe within the narrow tunnels. So, many Tunnel Rats decided they’d rather go without one.

This work was mentally and physically tedious, and it was not uncommon for men to give up after a few runs.

Read another story from us: Booby Traps of the Vietnam War

However, according to Sapper Jim Marrett, a former Tunnel Rat, there was a surprisingly lower casualty rate than one might expect among the Tunnel Rats—most war casualties occurred above ground.

In the midst of all the difficulties, the Tunnel Rats were largely successful. The bravery of these men led to the discovery of several Viet Cong facilities, including their headquarters. The Tunnel Rats’ contribution to the war paved the way for the adaptation of the United States military to a new level of non-conventional warfare.