On December 23rd, 1944, twenty-four-year-old Tuskegee Airman Lawrence Dickson took off in his Mustang P-51 on a reconnaissance mission over the Austro-Italian border. On his return journey, witnesses reported that engine failure appeared to be the cause of the crash that took Dickson’s life.

He left behind a young wife and a two-year-old daughter in Harlem, New York.

Captain Dickson was an experienced pilot with a Distinguished Flying Cross on his 68th mission as part of the Tuskegee 332nd Flying Group.

A wingman who witnessed the crash was convinced he had seen Dickson eject, but a search failed to reveal either burning wreckage or a parachute against the snow.

Further searches for the crash site also ended in failure, and in 1949 the Pentagon listed Dickson as Missing In Action (MIA) and confirmed that his body was unrecoverable.

The border region where the crash site was finally discovered in 2012 is part of the mountainous Alpine region that also stretches across France and Switzerland.

The site, near Hohenthurn in Austria, was identified by Austrian researcher Roland Domanig and excavated by an Austro-American team over four weeks in the summer of 2017 by teams from the Universities of New Orleans (USA) and Innsbruck (Austria).

Human remains were discovered, and identification was made using a DNA sample from Dickson’s daughter, Marla Andrews, as well as another relative.

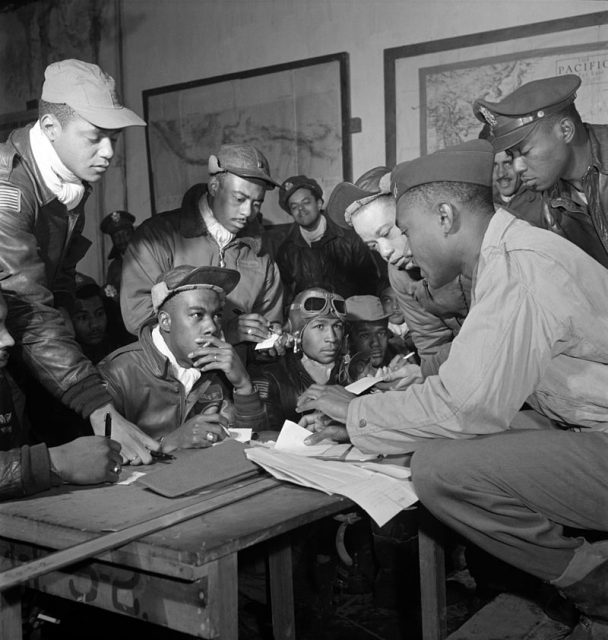

The so-called Tuskegee Airmen shattered racial barriers during WWII. The 332nd Fighter Group and the 447th Bombardment Group were set up to train African-Americans in fighter plane flying and maintenance.

P-40 Warhawk.

Dickson was part of the 100th Squadron, the first all African-American flying group, which was deployed to Northern Italy in the spring of 1944.

Dickson most likely trained on a Curtis P-40 Warhawk, since the Mustangs did not arrive in Italy until July 1944. When they did, they had their tails painted red to signify they were part of the “Red Tails” flying group.

They were also called the Red Tail Angels and received praise from the bomber squadrons they escorted on raids into Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Germany.

In all, the Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 sorties during WWI across North Africa, Sicily, and the Northern Italian frontier.

On one mission they accompanied B-17 bombers over 1,600 miles (2,575 kilometers) to destroy the Daimler-Benz tank factory in Berlin. On another, the pilots of the 99th Squadron set a record of destroying five enemy aircraft in less than four minutes.

The record of the Tuskegee Airmen reflected the fact that the men involved were highly motivated and made use of valuable pre-war flying experience.

They earned in excess of 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, which helped the eventual integration of African-Americans across all of the US Armed Forces.

By the end of the war, the Tuskegee project had trained 1,000 pilots and more than 14,000 navigators, bombardiers, aircraft mechanics, air traffic controllers, and every other role associated with running a successful squadron.

A popular myth arose during WWII that the Red Tails had never lost a bomber in all of their escort deployments. However, post-war declassification revealed that they had lost approximately 25 bombers. Even so, that figure is still much better than the average of 45 losses recorded by every other USAAF escort squadron.

At the end of the war, the Tuskegee Red Tail Airmen could point to their record with pride. Thirty-six German planes shot down in the air and 237 destroyed on the ground, as well as countless rail and road vehicles.

Read another story from us: The Legendary Tuskegee Airmen of World War Two

Amongst the wreckage uncovered by the researchers was part of a harmonica that keen musician Lawrence Dickson would keep in his pocket whenever he flew.

“Little things like that have been quite comforting,” said Ms. Andrews.