By August 1944, a favorable end was in sight for the Allies, and efforts were being ramped up to gain a final, definitive advantage over the Axis powers.

Not every effort to stay ahead of the curve was a success, though. Operation Aphrodite was one initiative that many would rather forget.

Unmanned Bombers: What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

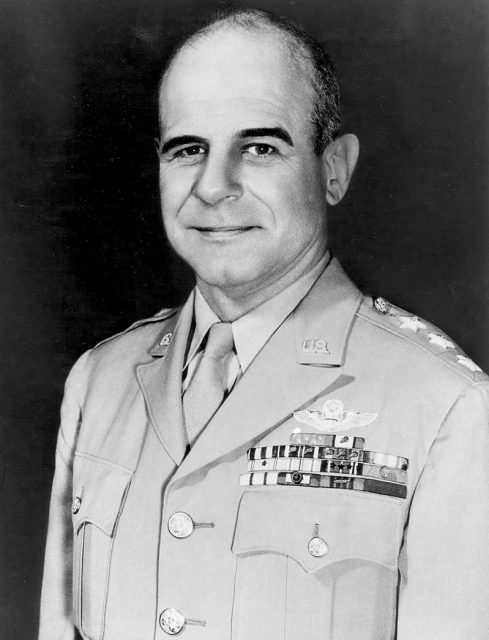

Operation Aphrodite was the brainchild of General Henry H. Arnold, who got the idea approved by General James H. Doolittle on June 26, 1944.

It was a good concept in principal: aging Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers would be repurposed instead of being relegated to the scrapyard.

The planes were stripped of all extra weight, including guns, armor, and seats. The canopies were also removed to allow an easy exit for the pilot and co-pilot.

The B-17 was then fitted with radio remote-control equipment and two television cameras in the cockpit. These cameras focused on the main instrumentation panel and the ground. Visuals were then transmitted from the B-17 to a CQ-17 that followed closely behind.

The plane’s reduced weight meant that it could carry more than twice its normal capacity in explosives, and it was duly packed with a British explosive called Torpex, a substance twice as powerful as TNT.

The B-17 would then be flown in the direction of an enemy target. The pilot and co-pilot would parachute out when they were just short of their destination, and the flying fortress would be flown straight into the target using remote control hardware, courtesy of the CQ-17 crew members.

It was a kamikaze-style mission that, in principle, would result in no casualties among crew members while at the same time was designed to inflict maximum destruction on its targets.

Bombers Away

Suffolk’s 562nd Bomb Squadron was picked to execute Project Aphrodite, and 14 missions in total were flown. However, the success rate was somewhat hit and miss – in a very literal sense.

Operation Aphrodite launched her maiden mission on August 4, 1944, for a functional combat test. Out of four planes launched, only one made it anywhere near its target, which was Watten, Wizernes in Germany.

The B-17 crashed 1,500 feet (457 meters) away from where it was supposed to, doing far less damage than intended.

It’s not known for sure, but it’s likely that the plane was shot down by German ground fire. This was another flaw in the strategy: a low-flying B-17 was a pretty easy target for Luftwaffe Flak fire because it generally flew at around 2,000 feet (609 meters).

The other three planes didn’t reach their targets because of radio control failure. There were two casualties as a result of the exercise: a flight engineer and a pilot. And two acres of countryside in Orford were destroyed, leaving a huge crater.

The Ipswich and Sweden Incidents

One would think that the failure of the first four missions might have acted as a cautionary tale to General Arnold, Major General Doolittle, and their men, but despite the first four flights’ bad showing, Operation Aphrodite pressed on.

Radio control issues plagued each mission, causing two very notable and almost disastrous incidents.

On August 6, 1944, the CQ-17 radio pilots lost control of another plane headed for Watten. This time, the signal was lost near Ipswich.

The plane began to circle the Suffolk town precariously for several minutes, threatening to go crashing down into the densely populated area.

Thankfully, the crash never came and the B-17 ultimately fell into the sea, harming no one.

Allied civilian casualties would have caused an international incident and a large-scale tragedy that could have been avoided completely had Operation Aphrodite been scrapped. But still, the Generals persisted.

Sweden was neutral during the War, but that didn’t stop the B-17 from blowing some of it up. On October 30, 1944, following several unsuccessful B-17 missions and despite new radio control hardware, two more missions were launched.

The planes had been redirected towards Berlin. Their primary target, the Heligoland U-Boat Pens, was not achievable because of bad weather.

The first plane crashed into the North Sea because it ran out of fuel. The second flew on to Sweden, where it crashed in spectacular fashion.

The two crew members had already bailed out over Denmark. The “Mothership” pilots had lost radio control some time shortly after that, and the B-17 (serial number 42-30066) went down at the Vissla Kvarn (Whistle Mill), south of Trollhättan.

The crash left a massive crater and the impact is said to have shattered windows up to three miles away. Miraculously, there were no civilian casualties, but the local landscape was decimated.

When It All Came Crashing Down

Only two missions followed the crash landing in Sweden. One crashed outside the German town of Haldorf, and the other was shot down before it could reach the Oldenburg Power Station.

At this stage, even for its die-hard supporters, the writing was on the wall. Finally, on January 27, 1945, General Spaatz officially ordered Major General Doolittle “not to launch against the enemy until further orders.”

Operation Aphrodite and its similarly doomed Naval counterpart, Operation Anvil, will always serve as examples of foolhardy innovation gone wrong.

Among its casualties were Lieutenant Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. – brother of future President John F. Kennedy – and several other unwittingly doomed American flight crew members.

Read another story from us: The B-17 Flying Fortress in 26 Images

Aphrodite Today

Today, remote-controlled drone aircraft operate successfully for various purposes throughout the world. But the concept was just too much, too soon for the creators and victims at the time of Project Aphrodite.

One of the most telling differences in the development of modern unmanned flying machines is that the first attempts at it didn’t see the aircraft filled with explosives. Perhaps there’s a lesson in that.