In August 1942 the Japanese were hell-bent on taking the (then Australian) city of Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea. Trying to stop them were a group of Australians, but what turned the tide in the latter’s favor was one man.

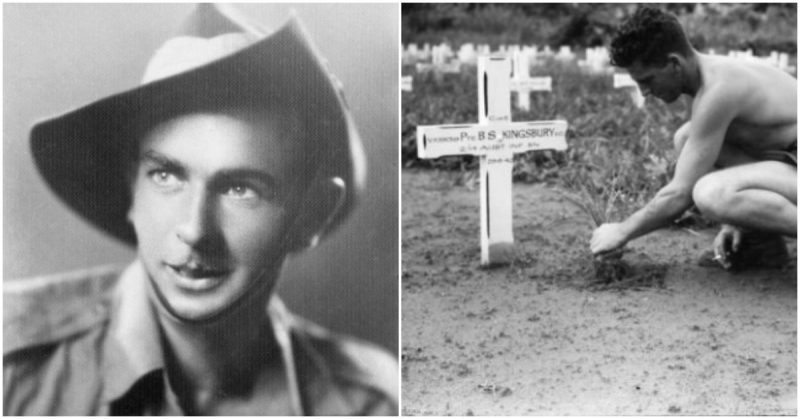

Bruce Steel Kingsbury was born on January 8, 1918, in Melbourne, Australia to British immigrants. He did well at school and qualified for a scholarship at Melbourne Technical College.

When he was five years old, Kingsbury met his best friend, Allen Avery. They were inseparable. After a brief stint working at his father’s real estate business, Kingsbury quit to go and work on a farm to be near his friend.

They left their jobs in 1936 to walk to Sydney in New South Wales working on various farms as they went. Returning home later that year, they enjoyed several years of peace until the war broke out in Europe. Despite his parents’ disapproval, on May 29, 1940, Kingsbury joined the Australian Imperial Force and was assigned to the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion.

When he discovered Avery had enlisted with the 2/14th Infantry Battalion, he applied for a transfer to be with his best friend. After basic training, they were assigned to the 7th Division and in late 1940 were sent to the Middle East. Continuing their training, they were sent to Tel Aviv, Egypt and Syria en route to Lebanon. There in 1941, they were involved in combat against the Vichy French before being recalled to Australia in January 1942 for further training.

Their next stop was the island of New Guinea – which held a unique position during WWII. The Japanese had captured the (then) Australian territories of New Guinea and Papua, as well as the (then) Dutch territory of western New Guinea. Allied troops, however, managed to hold onto Port Moresby on New Guinea (now Papua New Guinea).

The Japanese attempted to take the Port on March 4, 1942, by launching the Battle of the Coral Sea. Their goal was to take Port Moresby and the Allied-held island of Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. With those in Japanese hands, their grip over the South Pacific would be absolute.

It was the first time aircraft carriers were involved in a battle and also the first naval conflict in which no ships fired at each other. They did not need to as both used planes to devastating effect.

On May 8 the battle ended with the Allies remaining in control, but Japan was determined to capture Port Moresby. On July 21 they landed troops on the beaches near Gona and Buna on northeast Papua. To reach the Port, they followed the Kokoda Track over the Owen Stanley Range.

Despite the Australians best efforts, the Japanese took the Kokoda airfield on July 29. By August 9, the town of Kokoda town had fallen, as did Deniki shortly after. Isurava was next.

The Australian forces had been devastated. Along with the constant fighting, the Kokoda Trail passed through the tropical jungle, causing disease. Planes for aerial resupply were few, and a drop was made almost impossible because of the thick canopy of trees.

Also, they had no heavy weapons or ammo as it was thought they were too cumbersome to carry in the thick jungle terrain. The Japanese, however, had no such qualms. As a result, the Kokoda Trail Campaign forced the Allies to rethink their strategies – but that was done later.

With the fall of Deniki, the Australians retreated, set their HQ on a hilltop above Isurava and dug in. The fighting resumed on August 26 – the day the 2/14th, with Kingsbury and Avery, arrived to help reinforce the exhausted troops.

Japanese Major General Rikugun Shōsh Tomitarō Horii ordered a major assault on August 28. His force of about 2,500 men had outnumbered the original Australian force, but with the arrival of Kingsbury’s unit, they were equal in number.

The following day, the Japanese broke through the Australian right flank and began pushing them back away from their HQ. Most of Kingsbury’s unit had been killed in the fierce hand-to-hand combat, so he and Avery volunteered to join another platoon who were preparing for a counterattack.

Corporal Lindsay Bear, another survivor of the 2/14th, was too wounded to fight on, so Kingsbury took his Bren light machine gun – a misnomer as the early models weighed more than 22 pounds.

Lieutenant Colonel Philip Edington Rhoden, the commanding officer of the 2/14th, later said, “You could see his Bren gun held out and his big bottom swaying as he went with the momentum he was getting up, followed by Alan Avery. They were cheerful. They were going out on a picnic almost.”

The firing was so intense that the jungle was stripped of its vegetation in minutes. Kingsbury yelled, “Follow me! We can turn them back!”

The Japanese were caught off guard as the fierce Australian juggernaut fired at them from his hip, followed by other enraged Australians doing the same.

Kingsbury continued until a Japanese sniper shot him. Seeing his childhood friend fall, Avery went berserk, shooting madly. Then Avery carried his friend to the medical post but, tragically, he was already dead.

Military historians believe had it not been for Kingsbury, the Japanese would have overrun the Australian position. As they did not, Kingsbury was awarded a Victoria Cross – Britain’s highest military award.