In 1975, Saigon fell, bringing to a close a brutal conflict that had raged through Vietnam for 30 years. This conflict saw both the French and American military taken severely to task by North Vietnamese peasants.

With the end of this conflict, anti-war sentiment in America was at its highest. The literature and films coming out reflected this.

Such anti-war sentiment lasted until the Soviet Union collapsed and the American military had success in Iraq and Kuwait. But then, 9/11 came along with the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Once again, anti-war sentiment arose.

Now, it seems, a more balanced view of history is coming out.

One such account can be found in the latest book by renowned author Max Hastings. His new book Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975, is a well researched, balanced, and inclusive view of the conflict in Vietnam.

Instead of taking the more usual route of writing from the American perspective, Hastings has taken on the voice of the Vietnamese people who suffered cruelly during the conflict.

The overarching feeling one gains from Hastings’s book is that neither the Viet Cong nor the Americans and French emerge with much credit.

Hastings closely examines the long-view of history and concludes that history is not inevitable.

He suggests that Vietnam would not have succumbed to communism after 1975 if their original colonial masters, the French, had taken the time and trouble to ensure that credible local leaders were trained to run the country after they pulled out in 1945.

France was still reeling from the German invasion of their country during WWII, so instead of undertaking a controlled pull-out, they embarked on an attempt to subjugate the Viet Minh insurgents and their communist ideals.

They achieved nothing more than waging a bloody conflict that cost 90,000 French soldiers their lives and which ended in humiliation and sound defeat for the French.

Again, in Hastings’s balanced view, he writes that the Viet Minh commander, Vo Nguyen Giap, would not have retained his leadership position after experiencing crippling defeats in 1951 if he had been enlisted in a Western army. He had the political backing of Ho Ci Min and was never held to account for the ever-increasing body count.

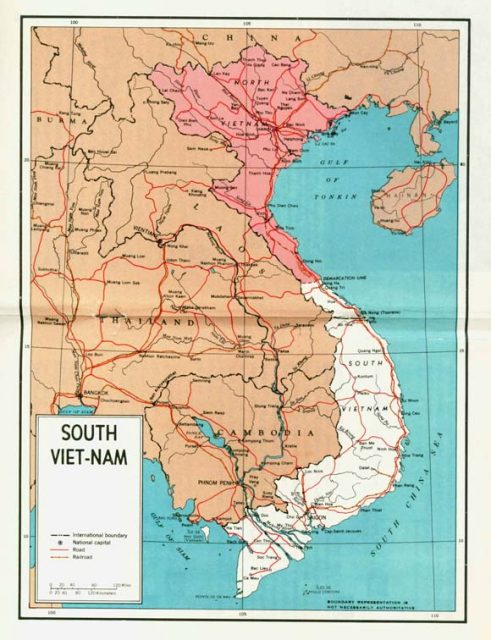

Giap’s resounding defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 marked the beginning of the end for the French. In 1955, the French fled, having partitioned the country along the 17th Parallel. This left Vietnam with communist masters in the north and a pro-West southern portion.

Instead of the US heeding the French experience, they ignored it on the back of larger Cold war problems and the constant desire to fight communism wherever it occurred.

In 1947, the US President, Harry Truman, had declared in a speech to Congress that the US would always work to free people subjugated by armed minorities. This was just a cover for the American desire to obliterate communism, and by 1950, the Americans were paying the debt left by the retreating French.

Dwight D. Eisenhower saw the fall of the South Vietnamese as the first in a row of dominoes that would soon lead to the whole of South-East Asia falling under the communist ideology.

He took his appeal to Britain, asking Churchill to help. But the Prime Minister responded that as Great Britain had not been able to hold onto India for themselves, they were not about to try and hold onto Indo-China for the French.

From that point on, the Americans supported South Vietnam, first by sending funds and then American troops to help the South Vietnamese prevent a communist takeover.

One of the questions posed by history is: would the Americans have gone all in South Vietnam if John F Kennedy had not been assassinated? Hastings believes that they would, as Kennedy did not think he could allow Vietnam to fall to the communists and then ask the American public to vote him back into power.

Kennedy had already authorized the deployment of 16,000 American advisors to Vietnam before his assassination. Johnson did not want to be the American president that lost Vietnam, so he did nothing to stop the steady influx of American men and materials to South Vietnam.

One of the things that comes through very clearly in Hastings’s book is the motivations of many of the American politicians during these war years. He also paints clear pictures of how the Viet Cong insurgents, the American grunts, the Vietnamese people, and the NVA soldiers all saw the war.

Hastings devotes pages of his book to describing the feelings of the American soldiers. These men often had to make do with sub-standard equipment as contracts to supply materials, guns, and ammunition had been sold on the political battlefield back home.

He clearly portrays the horror of combat and the impotent feelings of many junior officers who struggled to make themselves understood in thick jungle with the cacophony of a war raging around them.

Hastings also describes the pyrrhic victory of the Tet Offensive in 1968, when the Americans inflicted heavy defeats on the Viet Cong but left the American public utterly appalled at the carnage. This led to public opinion swinging away from the war and demands that America find a permanent solution.

Five years and 22,000 lives later, the Americans pulled the last soldier out. Nixon’s vaunted political solution was doomed to failure and condemned the South Vietnamese to control by the communist north, but this was not Nixon’s concern.

Hastings then addresses the question of whether the war was pointless. He doesn’t think that it was. He believes that it saved many countries from communist domination including Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and perhaps even Australia.

Hastings goes on to make it clear that the American effort was fatally flawed in that it was not undertaken with a view of protecting the South Vietnamese people but from the requirements of domestic and foreign policy back home in the US.

The biggest losers in this war were the South Vietnamese people. During this conflict 2-3 million died, or to put it in perspective, 40 for every American casualty. All this on the back of American politicians who lied to their constituents and the world during the ten years of the war.

Hastings served as a war correspondent in Vietnam and was one of the last to leave, so he writes from an intensely personal perspective.

However, he is objective in this book, which is both balanced and authoritative. It contains a gripping, well-written narrative. He spares no-one’s sensibilities and ruthlessly slashes down some of the most popular beliefs about this bloody conflict.

Books about history should lead to a modification of the public’s understanding of the past and alter its future behavior. But with America’s intervention in Iraq, we see the same tragedy being initiated all over again.